The "Type A" time bomb: how personality profiles predict offshore accidents?

Part 3 of the Human Factors Revolution Series

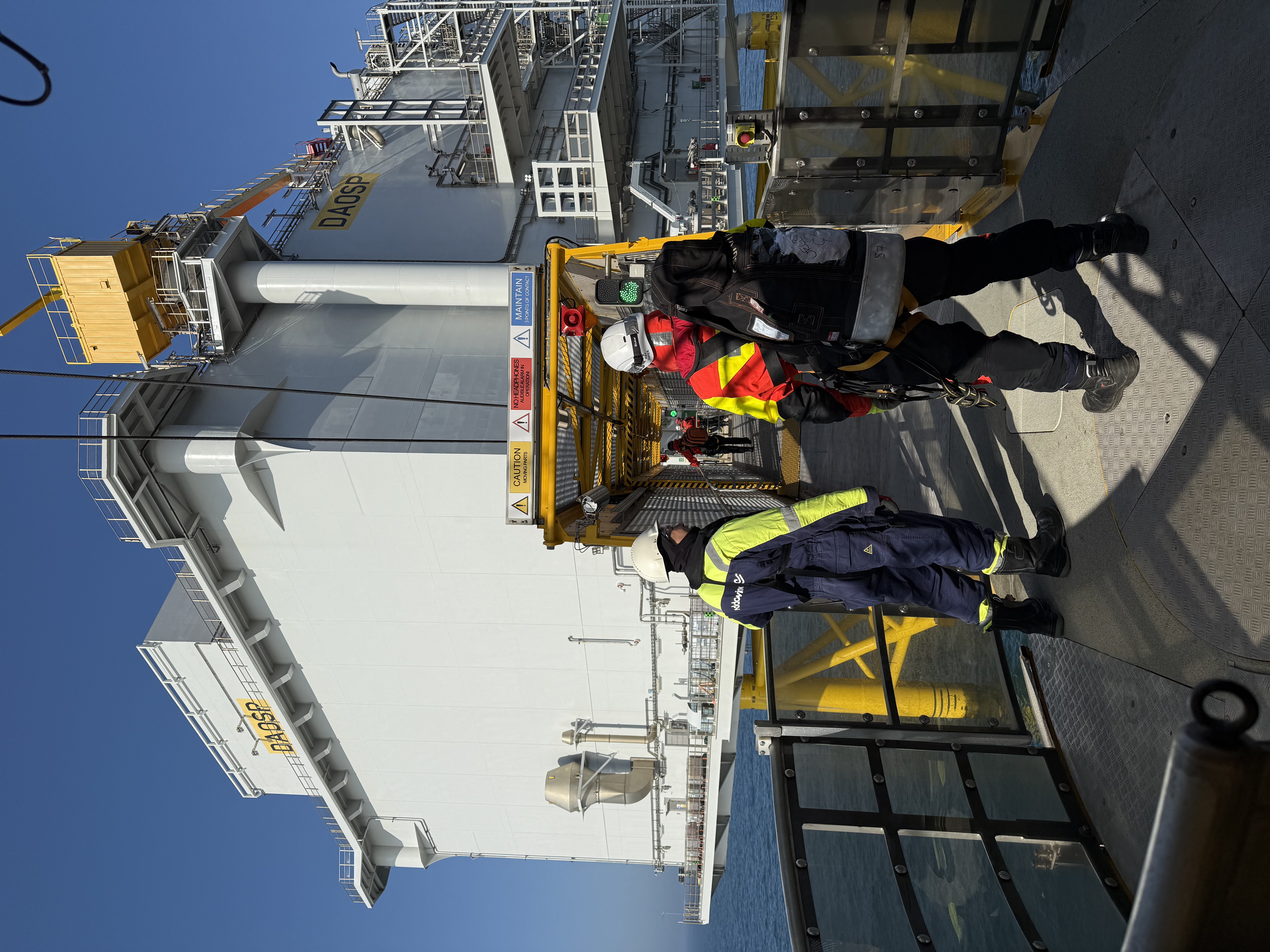

Picture an offshore drilling platform in the North Sea, waves pounding steel legs as a storm brews. The operations manager (let's call him “Jack”) paces the control room. He's known for beating every deadline, a reputation forged by barking orders and refusing to take "no" for an answer. Today, rig maintenance is running long, and Jack’s patience is paper-thin. “Skip the last pressure test,” he finally snaps to his crew, eyeing the clock. They comply. Hours later, alarms scream as an unchecked valve fails, triggering a gas release. Thankfully, disaster is averted by a hair’s breadth – a near-miss that leaves even Jack shaken. An internal report will later cite “excessive time urgency and rule-bending” as root causes. Jack’s Type A leadership style, once praised for productivity, nearly blew up the platform.

This scenario is not an outlier. High-risk operations in Europe and the Middle East often attract hard-charging personalities who thrive under pressure. These individuals exhibit what psychologists famously call the Type A behavior pattern – a coronary-prone profile first described in the 1950s by cardiologists Meyer Friedman and Ray Rosenman. Type A people are competitive, impatient, aggressive, and always racing the clock, unlike their more relaxed Type B counterparts. Decades ago, Friedman and Rosenman even linked this intense behavior pattern to elevated risks of heart disease, dubbing it “hurry sickness.” But emerging evidence shows that the Type A profile is also a safety time bomb. This third and final installment in our Human Factors Revolution series shines a spotlight on a controversial, data-backed position: high-risk industries not only cultivate Type A traits – they covet them – yet those same traits can trigger more accidents and erode worker well-being over time. We will delve into the science behind Type A behavior and accident proneness, share real (anonymized) case studies from incident investigations, and see how leading oil and gas companies in Europe and the Middle East are leveraging personality profiling in behavioral safety training. The goal is to understand how a person’s default temperament can influence on-site decisions, and what executives can do right now to defuse the “Type A time bomb” before it goes off. All insights are grounded in research and industry data – because recognizing the human element in safety isn’t just soft science, it’s hard ROI for high-hazard operations.

Coronary-Prone Personalities in the Oilfield

Before Type A became a corporate buzzword, it was a medical hypothesis. In the mid-20th century, Friedman and Rosenman observed common traits among their cardiac patients: unrelenting drive, impatience, and hostility. They coined the term “Type A behavior pattern,” arguing it was an important risk factor for coronary heart disease. In classic studies like the Western Collaborative Group Study, Type A individuals were more likely to suffer heart attacks than the more easy-going Type B personalities. The “coronary-prone” moniker stuck. Over time, the theory faced scientific debate (especially once tobacco companies oddly began funding Type A research), but the core idea endured: certain people carry a chronic sense of urgency that can impact their health and behavior.

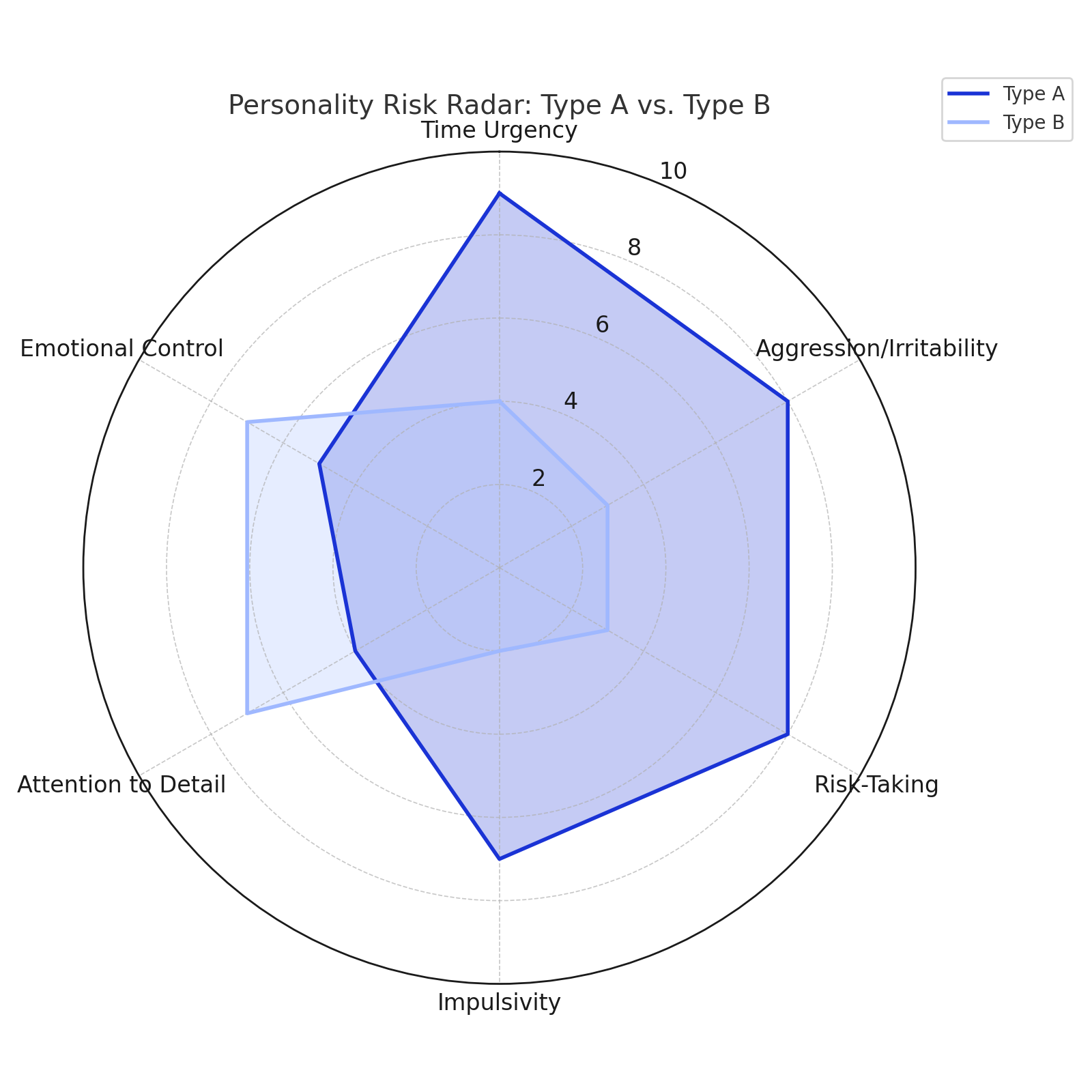

What exactly defines Type A behavior? Psychologist D. C. Price succinctly described it as a pattern of “competitiveness, aggressiveness, and achievement striving”. Type A individuals feel a constant pressure to do more in less time. They talk fast, move fast, and hate waiting. They often explode in anger at minor frustrations. Importantly, they are driven by time urgency – a feeling that every second counts. On the positive side, Type As are often high achievers and natural leaders, propelling projects forward. On the negative side, that “hurry-up” mindset can morph into risk-taking and carelessness under stress.Psychologists have found that Type As tend to be more erratic and error-prone on tasks, especially when deadlines tighten. In lab simulations, they make snap decisions and overlook details that more methodical people catch. In team settings, their aggressive communication style can intimidate others into silence – potentially stifling warnings or dissenting voices that might prevent a mishap.

It’s not hard to see how these traits play out in an industrial setting. Consider an offshore oil platform or remote drilling camp. Such environments naturally breed time pressure and competition: production targets must be met, downtime costs millions, and a macho “can-do” culture still pervades many crews. These conditions act like a magnet for Type A personalities. In interviews, oilfield supervisors often pride themselves on thriving under pressure, wearing Type A traits as a badge of honor (“I don’t need sleep; I need results”). Indeed, organizational psychologists note that high-risk occupations may select for Type A individuals, whether by self-selection or hiring bias. The excitement-seeking facet of personality (closely tied to Type A) means risk-takers often choose risky jobs, from wildcat drillers to test pilots. Companies, in turn, may favor go-getters who appear “hungry” and relentlessly driven, especially for leadership roles. The result is a workforce where many of the key players share the same temperament – one that can be both a strength and a dangerous liability.

Type A Traits: Fuel for Performance… and Accidents

Do Type A personalities actually experience more accidents on the job? Research says yes. Pioneering studies in the North Sea oil industry first sounded the alarm over 30 years ago. In a landmark survey of 194 offshore workers, Cooper and Sutherland (1987) found that Type A behavior was a significant predictor of increased accident rates offshore. This held true even after accounting for job stress and other factors. In other words, individuals who scored high on Type A traits (impatience, hostility, urgency) also tended to have more mishaps and near-misses. The same study found these Type A workers reported lower mental well-being – higher anxiety, lower job satisfaction – compared to their less driven peers. Figure 1illustrates this pattern: in the offshore workforce, the high Type A group experienced a higher incidence of accidents and poorer self-rated mental health than the Type B group (the more relaxed personalities). This dual impact – on safety and wellness – earned Type A its “time bomb” nickname. The constant tension and impulsivity that can push a project forward can also undermine careful decision-making and personal resilience.

Later studies have reinforced these findings. A meta-analysis of personality and workplace safety concluded that certain traits align consistently with accident risk: low agreeableness (i.e. uncooperative or hostile tendencies) and high neuroticism (proneness to stress) correlate with more accidents. But Type A – which overlaps with a combination of these tendencies (hostility, urgency, impatience) – is particularly problematic. Sutherland and Cooper, who extensively studied North Sea platforms, noted that Type A individuals are more likely to take shortcuts and engage in unsafe acts, especially under time pressure. The heightened sense of urgency that defines Type A can lead them to underestimate hazards in the rush to accomplish tasks. One analysis went so far as to label Type A managers as “accidents waiting to happen” if their impulsivity isn’t kept in check (Shahidi et al., 1991, as cited in Henning et al., 2009).

Crucially, Type A traits also affect team dynamics on offshore installations. These personalities can dominate conversations and decision-making. Psychologists refer to a “culture of busyness” that often surrounds Type A leaders – meetings are hurried, all tasks are urgent, and there is zero tolerance for delays. While this can foster high productivity, it can also suppress open communication. Crew members may hesitate to voice safety concerns or fatigue if their boss is a Jack-like figure who explodes at bad news. Over time, such a climate erodes the safety culture, creating conditions where warning signs get missed or ignored. A peer-reviewed study in 2021 found that offshore workers who felt unable to speak up (often due to intimidating, Type A-style bosses) had significantly higher rates of unsafe behaviors and accidents (Al-Mentouri et al., 2021). In short, Type A isn’t just a personal style – it’s a workplace hazard if unmanaged. Companies that recognize this are beginning to treat extreme Type A behaviors as red flags – signals that an individual might need coaching or that a team might need balancing with calmer voices.

Real Incidents: When Urgency Trumps Safety

The oil and gas industry’s history is peppered with cautionary tales where Type A tendencies played a role in accidents. We’ll look at two anonymized case studies (drawn from public reports) that illustrate how impatience, competitiveness, and time pressure can align with disaster.

Case Study 1: The 2010 Gulf Blowout. An offshore drilling project in the Gulf of Mexico was running 43 days behind schedule and $21 million over budget. Intense corporate pressure to catch up had managers and crews working at a frenetic pace. According to investigation reports, decisions were made to skip certain well safety tests and rush the final cementing process in order to save time. On the night of April 20, 2010, those chickens came home to roost. A series of missed warning signs and hurried judgments led to a catastrophic blowout, an explosion that killed 11 crew and unleashed the worst oil spill in U.S. history. In the aftermath, analysts noted that the rig’s leadership exhibited classic Type A culture: they were “ahead of the curve” performers rewarded for speed, who downplayed concerns that might slow progress. One senior manager had a mantra: “Drive forward, don’t dwell on negatives.” The U.S. Presidential Commission on the accident later cited “organizational hubris” and a culture that valued production over safety as underlying causes. In plain terms, a Type A drive for results – and the resulting shortcuts – lit the fuse of a time bomb.

Case Study 2: North Sea Platform “Piper Alpha.” In 1988, a production platform in the North Sea Piper Alpha suffered a devastating series of explosions that claimed 167 lives. The official inquiry (the Cullen Report) identified a cascade of human errors behind the disaster. One pivotal error occurred during a maintenance shift change: an outgoing crew removed a safety valve from a gas condensate pump for repair, but the incoming crew was not properly informed. Under pressure to maintain output (the platform was handling 10% of the UK’s oil at the time), the incoming shift restarted the pump without the safety valve, triggering a massive gas leak. The ensuing explosions destroyed the platform. Digging into the culture on Alpha, investigators found an almost militaristic work ethic – downtime was unacceptable, and crews competed to solve problems fastest. The permit-to-work system was treated casually in this atmosphere of urgency. As one survivor recounted, “Everyone was in a rush, all the time.” In this case, competitiveness and haste (hallmarks of Type A culture) led to miscommunication and a fatal oversight. The lesson: **all the engineering redundancies in the world can be undone by a human who is too much in a hurry or too confident to double-check.

Other examples abound. A Norwegian North Sea study noted that many “high potential incidents” (near-accidents with major risk) involved supervisors described by peers as “aggressive go-getters” – people with reputations for cutting corners to meet targets (Heitmann et al., 2019). In the Middle East, a 2017 analysis of a large oilfield blowout cited poor risk perception under time pressure as a contributor; interviews revealed that managers were vying to break drilling speed records – a competitive drive that normalized risk-taking. These stories underscore a crucial point: high-risk environments often amplifyType A traits until they become dangerous. The same qualities that help teams hit ambitious goals can, in excess, set the stage for accidents. Knowing this, what can companies do? One approach gaining momentum is to measure and manage these personality factors directly – essentially, to profile the “human factor” the way we profile technical risks.

From Profiles to Prevention: Using Personality in Safety Training

Historically, safety training in oil and gas treated all workers the same – assume everyone has the same baseline attitudes, give them rules and PPE, and expect safe behavior. Today, forward-thinking organizations are moving toward a more personalized approach: behavioral safety training that incorporates personality profiling. If certain individuals are predisposed to risky behaviors (like impulsivity or rule-bending), wouldn’t it make sense to identify them and coach them differently? This is the logic behind new programs that combine human factors training with personality assessments.

Some companies started experimenting with this idea years ago. In the 1990s, at least one major drilling contractor was already using a Predictive Index personality test to screen offshore installation manager (OIM) candidates. The test measured traits like dominance, patience, and risk tolerance – looking for profiles that fit a safety-conscious leader. Others used tools like PAPI (Perception and Preference Inventory) to evaluate how incoming staff might handle rule-following and stress. Back then, these assessments were mostly used in hiring or promotion decisions (and not widespread – a survey found the majority of North Sea firms still did not use psychometric tests in the 90s). But it set a precedent: personality does affect safety performance, so we can potentially manage it.

Fast forward to today, and behavioral safety training is catching on to the power of profiling. One notable example is the use of Safety Quotient™ assessments, developed by firms like TalentClick specifically for high-risk industries. These are short questionnaires that measure six key personality traits linked to safety outcomes: Resistant, Anxious, Irritable/Impatient, Distractible, Impulsive, and Thrill-Seeking. Workers receive a score or profile highlighting any high-risk tendencies – for instance, a person might score high on “Impulsive (Seeks excitement, takes risks)” and “Irritable (easily frustrated under stress)”, which closely align with the classic Type A pattern. Rather than use this to hire or fire, companies are using it as a coaching tool. The philosophy is: self-awareness is the first step to safer behavior. When workers know their own risk factors, they can learn specific strategies to compensate (and supervisors know where to give extra support).

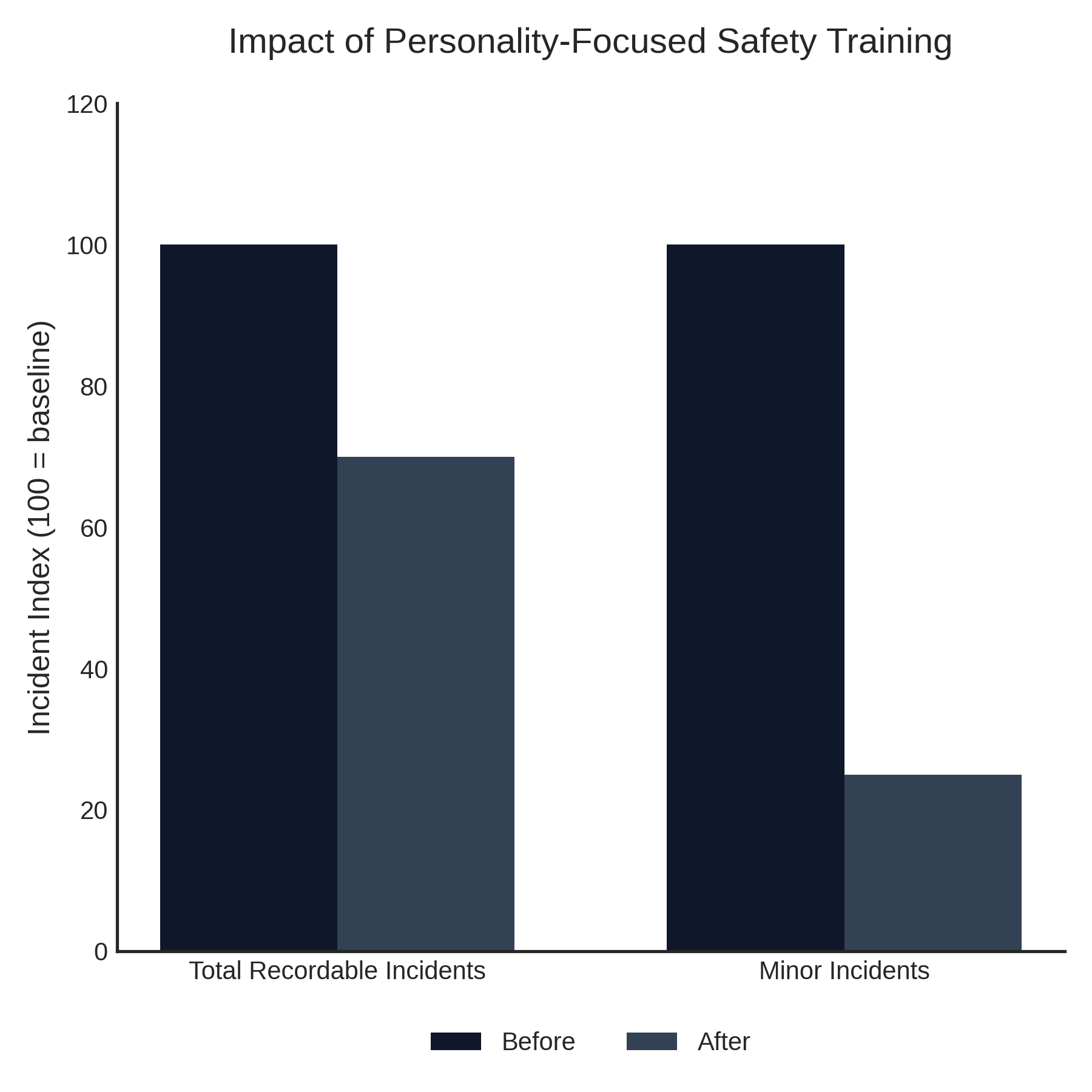

How does this look in practice? Oil and gas companies in Europe and the Middle East have begun integrating personality assessments into their safety programs as part of a broader human factors training push. Typically, it works like this: Employees take a confidential personality-risk assessment(often online, 20–30 minutes). They then receive individualized feedback and training. For example, an impulsive worker might go through a “safety mindfulness” module that teaches pausing and double-checking decisions, while a very competitive, Type A team leader might receive coaching on active listening and encouraging team input (to counteract their instinct to dominate discussions). One global oil & gas company that implemented such a program reported remarkable results. The company deployed a Safety Self-Awareness training where participants first took the Safety Quotient questionnaire to pinpoint their personal risk traits. They then attended workshops (or e-learning) tailored to those results – essentially learning how to “interrupt” their unsafe tendencies before an incident occurs. Managers were trained on the six personality factors as well, so they could adjust their leadership approach to the profiles of their team. According to a case study from the program, incident rates fell by 30% in the first six months and minor injuries and near-misses dropped by 75% after rolling out the training. Participants overwhelmingly recommended the training to others, citing that it “opened their eyes” to behaviors they never realized were risky.

Beyond formal programs, simply discussing personality and risk has benefits. Some European offshore companies have begun adding a module on Type A behavior and stress management in their human factors training sessions. Workers are encouraged to reflect on how their temperament affects their safety choices. For instance, do you speed through checklist steps when you’re feeling impatient? Do you hesitate to report a problem because you don’t want to hurt your “can-do” reputation? These discussions, executives report, help to destigmatize the human side of safety. It’s not about labeling someone as a “bad actor,” but recognizing that everyone has risk tendencies – and those can be changed. As one HSE director in Abu Dhabi put it, “We used to assume attitude was immutable. Now we treat it like any other risk factor: measurable and manageable.”

The Controversy: Rewarding the Risk Takers

It’s important to acknowledge a controversial tension here. High-risk industries have long rewarded Type A traits – urgency, boldness, decisiveness – in their leaders. These industries often run on tight margins and tighter timelines. A drilling superintendent who can shave days off a rig schedule by pushing hard is celebrated (and often promoted). A construction manager who drives her crew to finish a project early is praised as efficient. Thus, a paradox arises: the very personality characteristics that raise accident risk are frequently seen as markers of success in the business. This can create mixed messages in an organization. On paper, the company might preach “safety first,” but in practice it promotes the managers who never take no for an answer. Executives may find themselves in a bind – how do we value ambition and high performance without encouraging the dark side of Type A behavior?

The first step is to get real about the data. It is now well-established that human factors underpin the majority of accidents in high-hazard environments. Studies across oil & gas, aviation, and mining attribute 60–80% of accidents to human errors or unsafe behaviors. Many of these errors are not simply “oops, I didn’t know the rule.” They are errors made by experienced people under stress, fatigue, or time pressure – in other words, contextual errors, often driven by the culture and personality factors we’ve discussed. It’s also increasingly clear that Type A behavior correlates with indicators of poorer long-term well-being (e.g. higher stress, burnout) even among tough offshore workers. In an era where companies are paying more attention to mental health, this cannot be ignored. A “win at all costs” culture might win today and lose tomorrow if it grinds down your workforce or leads to a major accident.

So, what is the controversial position we propose? We posit that high-risk sectors must confront their own love affair with Type A behavior. The data-backed reality is that extreme urgency, hyper-competitiveness, and aggression undermine safety in the long run, no matter how much they may boost short-term metrics. This doesn’t mean we want a workforce of complacent people – far from it. It means redefining what a “high-performing employee” looks like. Perhaps the hero is not the manager who delivered under budget by skirting the edge, but the manager who paused a job when things didn’t feel right, averting disaster. Perhaps we start celebrating the driller who calls a time-out to regroup the crew after 12 hours on duty, not just the one who powers through. This is a mindset revolution. And like any revolution, it will meet resistance from those who say “this is how we’ve always done it” or “we don’t have time for touchy-feely stuff.” But as we’ve shown in this series, incorporating human factors – from mental health to personality – is not touchy-feely; it’s financially and operationally prudent. The companies that act on these insights are positioning themselves to avoid the next big accident and to have a healthier, more resilient workforce.

Gap Executive Takeaways: Defusing the “Time Bomb”

For executives in oil, gas, and renewable energy companies, the implications are clear. By paying attention to personality factors and tweaking your safety strategies accordingly, you can materially reduce risk. Here are five actionable takeaways to implement immediately:

· 1. Put Personality on the Safety Dashboard: Just as you track leading indicators like safety observations or equipment integrity, start tracking human factors data. This could mean instituting personality risk assessments for key roles or high-risk teams. Tools are available (some free, some commercial) to evaluate traits like impulsiveness, aggression, or conscientiousness. Use these profiles in safety meetings – for example, if you know your drilling supervisors skew Type A, acknowledge that and plan for it (extra cross-checks, rotation of decision-making, etc.). When planning a critical operation, consider the personality mix of the crew the same way you consider their technical qualifications.

· 2. Integrate “Type A Awareness” into Training: Augment your existing behavioral safety trainingwith a module on cognitive and personality biases. Teach crews about the Type A vs Type B concept, not to label people, but to discuss real behaviors. Role-play scenarios: e.g., a schedule pressure situation where someone might bypass a step – how should others respond? Encourage team members to call out unsafe urgency (respectfully). For instance, empower even junior staff to say, “I feel like we’re rushing – can we take a moment to double-check?” When you train leaders, coach them on active listening and emotional intelligence. A Type A leader can learn to modulate tone and pace – e.g., consciously slow down meetings, ask open questions rather than barking orders. These soft skills directly impact hard safety outcomes.

· 3. Adjust Schedules and Incentives to Reduce Toxic Pressure: Review your project schedules, rotation lengths, and bonus structures through a human factors lens. Are you unintentionally incentivizing risk-taking? For example, if bonuses are tied solely to production metrics, consider adding a safety performance component (so rushing and cutting corners doesn’t pay). Avoid scheduling scenarios that force Type A personalities to go into overdrive – like back-to-back 14-hour shifts or impossible deadlines. Build in “risk pauses” at critical phases of a project: explicit check-in points where the mandate is to slow down and review, which can counteract the natural speeding up that Type A folks gravitate toward. In essence, design your operations for a marathon, not a sprint, and communicate that ethos from the top.

· 4. Use Personality Data for Job Placement and Team Balance: When assembling teams for offshore projects or putting individuals into leadership roles, factor in their personality profilealongside their resume. High Type A individuals excel in certain crises – you might want that take-charge driver when fixing a sudden blowout, for instance – but maybe pair them with a detail-oriented deputy who can tap the brakes. On a drillship, if both the OIM and the toolpusher are ultra-Type A, recognize the risk of groupthink and add a protocol (or a person) to play devil’s advocate on decisions. Some companies quietly do this by ensuring a mix of backgrounds on a rig crew (a seasoned hand known for calm deliberation mixed with younger hungry go-getters). Deliberately balance your teams so that energy and caution strike the right equilibrium.

· 5. Promote a Safety Culture that Values Speaking Up Over Sucking Up: Lastly, set the tone thatsafety trumps ego or hierarchy. Executives should openly acknowledge that “even I can fall into the Type A trap” – and encourage employees to hold them accountable. Make “Stop Work Authority” truly mean something: if any worker, at any level, says stop, then stop – no reprisals. Celebrate examples of caution. For instance, circulate a brief in which a crew delayed a project for safety reasons and commend their restraint as much as you would commend finishing early. This sends a powerful signal that the company doesn’t just pay lip service to safety but would rather miss a deadline than attend a funeral. Over time, this helps moderate the unhealthy extremes of Type A culture. Workers see that taking a breather or asking for help is not a weakness but a strength.

By implementing these steps, executives can channel the positive aspects of Type A drive (energy, ambition, determination) into safe and sustainable performance, while curbing the negative aspects (impulsivity, tunnel-vision, aggression). It’s about striking a new balance. The offshore wind and oil sectors in Europe and the Middle East are poised for massive growth in the coming decades. The operations will only get more complex, the stakes higher. A “Human Factors Revolution” – one that includes understanding personality profiles – can ensure that as we scale up technologies and production, we don’t also scale up accident rates.

In conclusion, the Type A time bomb is a defusable threat. By recognizing it in ourselves, our workers, and our corporate cultures, we can take proactive steps to diffuse pressure before it ignites. When behavioral safety training embraces these insights, oil and gas companies unlock a new level of accident prevention – one that goes beyond procedures and PPE, straight to the core of who we are as humans on the job. This not only saves lives and money, but also improves the daily well-being of the men and women who power our energy industry. The rigs, platforms, and turbines of the future will be safer for it. And that is a legacy every executive can be proud of.

References

Alroomi, A. H., & Mohamed, S. (2021). Occupational stress, mental health, and safety behavior in remote oilfield operations. Journal of Safety Research, 78, 345–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2021.05.003

Cooper, C. L., & Sutherland, V. J. (1987). Job stress, mental health, and accidents among offshore workers in the oil and gas extraction industries. Journal of Occupational Medicine, 29(2), 119–125. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3819891/

Friedman, M., & Rosenman, R. H. (1974). Type A behavior and your heart. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

Henning, J. B., Stufft, C. J., Payne, S. C., Bergman, M. E., Mannan, M. S., & Keren, N. (2009). The influence of individual differences on organizational safety attitudes. Safety Science, 47(3), 337–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2008.05.003

Petticrew, M. P., Lee, K., & McKee, M. (2012). Type A behavior pattern and coronary heart disease: Philip Morris’s “crown jewel.” American Journal of Public Health, 102(11), 2018–2025. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300816

Roux, L. (2015, March 19). What’s your safety personality? (Revisited). SafetyPro Resources Blog. https://www.safetyproresources.com/blog/whats-your-safety-personality-revisited-personality-assessments

Sutherland, V. J., & Cooper, C. L. (1991). Stress and accidents in the offshore oil and gas industry. Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing Company.

TalentClick. (2025). How an oil & gas industry leader decreased incidents by 30% and strengthened safety culture. Customer case study. https://talentclick.com/resources/safety-self-awareness-case-study/