The isolation equation: how distance from shore multiplies mental health risks?

Part 2 of the Human Factors Revolution Series

Offshore wind has long been heralded as a marvel of engineering – turbines the height of skyscrapers, spinning in gale-force winds to power our cities. But behind the turbines and megawatts lies a quieter human story. Picture a maintenance crew living on a service vessel 100 km off the coast, the skyline long out of sight. For these technicians, distance from shore isn’t just a GPS coordinate; it’s a pressure multiplier on the mind. The farther offshore a wind farm is, the more isolated its workforce becomes – and evidence suggests this isolation equation amplifies stress, fatigue, and mental health risks in ways the industry is only beginning to understand. This article, the second in our Human Factors Revolution series, shines a spotlight on a controversial data-backed argument: every extra mile from shore deepens the psychological strain on workers, yet most wind farm companies are not prepared for the long-term wellbeing consequences. We will explore how distance and rotation schedules affect stress, detachment, and sleep, compare near-shore versus far-offshore experiences, and outline solutions from smarter rotations to mental health workshops to help wind farm companies balance operational efficiency with corporate wellbeing. All claims are grounded in research and real industry data, because getting this right is not just a “nice-to-have” – it’s mission-critical for the sustainable growth of offshore wind in Europe and the Middle East.

Beyond Sight of Land: Distance and Isolation in Offshore Wind

In Europe’s offshore sector, wind farms are being built farther out to sea than ever before. The average offshore wind installation in Europe is about 43.5 km from the coast, but newer projects in the North Sea stretch two to three times that distance. For instance, the UK’s Hornsea One wind farm – currently the world’s largest – sits 120 km offshore, making it the furthest wind project ever built. In Germany, some North Sea turbines stand 125 km from land. At these distances, daily boat transfers are impractical; instead, technicians spend weeks at a time living on service platforms or vessels near the turbines. This means that as wind farms push beyond the horizon, they push their people into deeper isolation.

Living and working in such remote environments creates a compound set of stressors. Offshore crews must contend with round-the-clock exposure to the work site. There is no going home at the end of a shift when “home” is a berth on a ship 100 km out at sea. Researchers note the lack of clear boundaries between work and rest in these settings: a technician may finish a 12-hour shift only to eat dinner and sleep in the same floating complex of steel where the turbines’ hum is a constant background. Privacy is scarce (many share small cabins), and the simple comfort of stepping outside for a quiet walk is replaced by the reality of endless ocean. Environmental conditions add to the strain, the noise of engines and generators, constant vibration, and even artificial ventilation can degrade one’s ability to relax and recover. In short, distance from shore forces workers to live in the work environment, a round-the-clock immersion that can erode mental well-being.

Isolation is more than a passing inconvenience; it has measurable psychological impacts. Studies of offshore oil & gas – the closest analog to far-offshore wind – show that extended time away from home is linked to higher anxiety and stress compared to onshore work (Parkes, 1992, as cited in Cooper & Sutherland, 1987). Offshore veterans often describe a creeping sense of detachment from normal life on land. One qualitative study of German offshore wind employees found that even though most considered themselves healthy, they consistently reported feelings of stress, fatigue, difficulty detaching from work, and sleeping problems while offshore. These accounts underscore what we can call the “isolation equation”: as the distance from shore increases, so do the intangible pressures on workers’ minds.

Mounting Psychological Strain with Every Extra Mile

Evidence from Europe’s offshore workforce is revealing just how much psychological strain is lurking below the surface of this industry. One of the clearest indicators is sleep quality. Nearly half of offshore wind workers in a 2018 survey reported that their sleep quality was worse during offshore deployments than when onshore. Think about that… for almost 50% of workers, sleeping out at sea is not just a little worse, but consistently worse over a period of weeks. It’s not hard to see why: the same study found that high exposure to noise, vibrations, and poor air quality on vessels or platforms was significantly associated with sleep troubles. Those in shared cabins had an even tougher time, with far more frequent awakenings at night. These conditions mean that by the time an offshore hitch is over, workers may be coming back to shore chronically sleep-deprived - a recipe for mental and physical exhaustion.

Sleep is just one piece of the strain puzzle. Fatigue builds up cumulatively during extended rotations. Research in the offshore oil sector noted that by the end of a typical two-week rotation, workers’ sleep quality and alertness had significantly worsened compared to the start of their hitch. In other words, even a standard 14-days-on schedule can leave crews running on fumes due to compounded fatigue. Many offshore wind rotations today also use 14-day on/14-day off cycles, mirroring oil and gas. If wind companies extend those rotations even further as projects go farther out (say, to 3-weeks on), the data suggest a sharp drop-off in well-being. A North Sea study found that three-week tours eroded workers’ well-being and increased fatigue, with only 25% of offshore staff reporting satisfaction with their work-life balance on such extended rosters. By contrast, shorter rotations (2 weeks or less) tend to have significantly higher satisfaction and lower stress—a pattern also reflected in fly-in-fly-out mining and construction jobs (Parkes et al., 2022). In remote Australian worksites, for example, longer work cycles and higher work/leave ratios were directly linked to greater psychological distress among FIFO employees, mainly because extended schedules leave workers with insufficient time to recuperate and reconnect with family. The message is clear: longer stints offshore = higher fatigue and distress.

Another documented challenge is psychological detachment – the ability to mentally disconnect from work during off-hours. Offshore, detachment is notoriously difficult. You might finish your shift, but you’re still on the wind farm. It’s telling that in interviews, wind technicians admitted to struggling with “switching off” from work while offshore, feeling perpetually in a work mode even when resting. This constant mental engagement can prevent proper recovery. Workers also spoke of the flip side of detachment: difficulty re-connecting with home life. After weeks away, reintegrating into family life can be jarring – one study noted that balancing work and family and readapting to domestic routines were major challenges for offshore employees, often made harder by the accumulated fatigue they bring back from sea. Spouses and children might have adapted to a rhythm in the worker’s absence, and the returning worker, exhausted and out of the loop, may feel like a stranger in their own home. Such detachment and re-entry problems can feed a cycle of stress and guilt that further weighs on mental health.

Perhaps the most sobering indicators come from looking at mental health conditions and even suicide riskin comparable industries. The offshore oil & gas sector, which has decades of experience with extreme remoteness, reports that roughly one in five workers suffers from clinical levels of psychological distress (e.g. anxiety, depression or substance abuse). This prevalence has hardly budged since the 1980s. In fact, this “19% invisible workforce” of struggling workers has often been masked by a tough-it-out culture. For context, 20% is substantially higher than mental illness rates in many onshore industries, implying the offshore environment itself is a contributing factor. Even more alarming, an analysis of U.S. data found suicide rates for oil and gas extraction workers are about 54 per 100,000, roughly double the average rate for working-age men. While the offshore wind industry is newer and does not yet have such longitudinal data, these figures serve as a warning: unchecked psychological strain in remote energy operations can have life-or-death consequences. It’s controversial to say distance from shore causes mental health risks – but we can say with confidence that the farther and longer people are isolated in high-pressure offshore conditions, the more we see serious mental health red flags emerge.

Comparing Near vs. Far Offshore: A Human Factor Perspective

Is a wind farm that’s 10 km offshore really that different, for workers, from one that’s 100 km offshore? Absolutely. The day-to-day experience of crews at a near-shore project versus an ultra-far offshore project can be as different as night and day. To illustrate, consider two scenarios:

· Scenario A: Near-Shore Wind Farm (e.g., 5–20 km out). A project relatively close to the coast often allows for daily crew transfers. Technicians might commute each morning by crew transfer vessel (CTV) and return by evening to sleep in their own beds or local accommodations on shore. Their workday is long – perhaps a 10 or 12-hour shift – but after work they can call home, have a normal meal on land, maybe even see family if home is nearby, or at least enjoy shore-based amenities. Psychologically, this pattern resembles a normal workweek routine, just with a boat ride instead of a car commute. Importantly, these workers get a daily mental “reset” offsite. Even if the job is physically demanding, the ability to disconnect each day tends to protect sleep quality and maintain a sense of normalcy. They remain embedded in society – seeing other people at the dock, sleeping without the drone of engines – which buffers against the loneliness that comes with isolation.

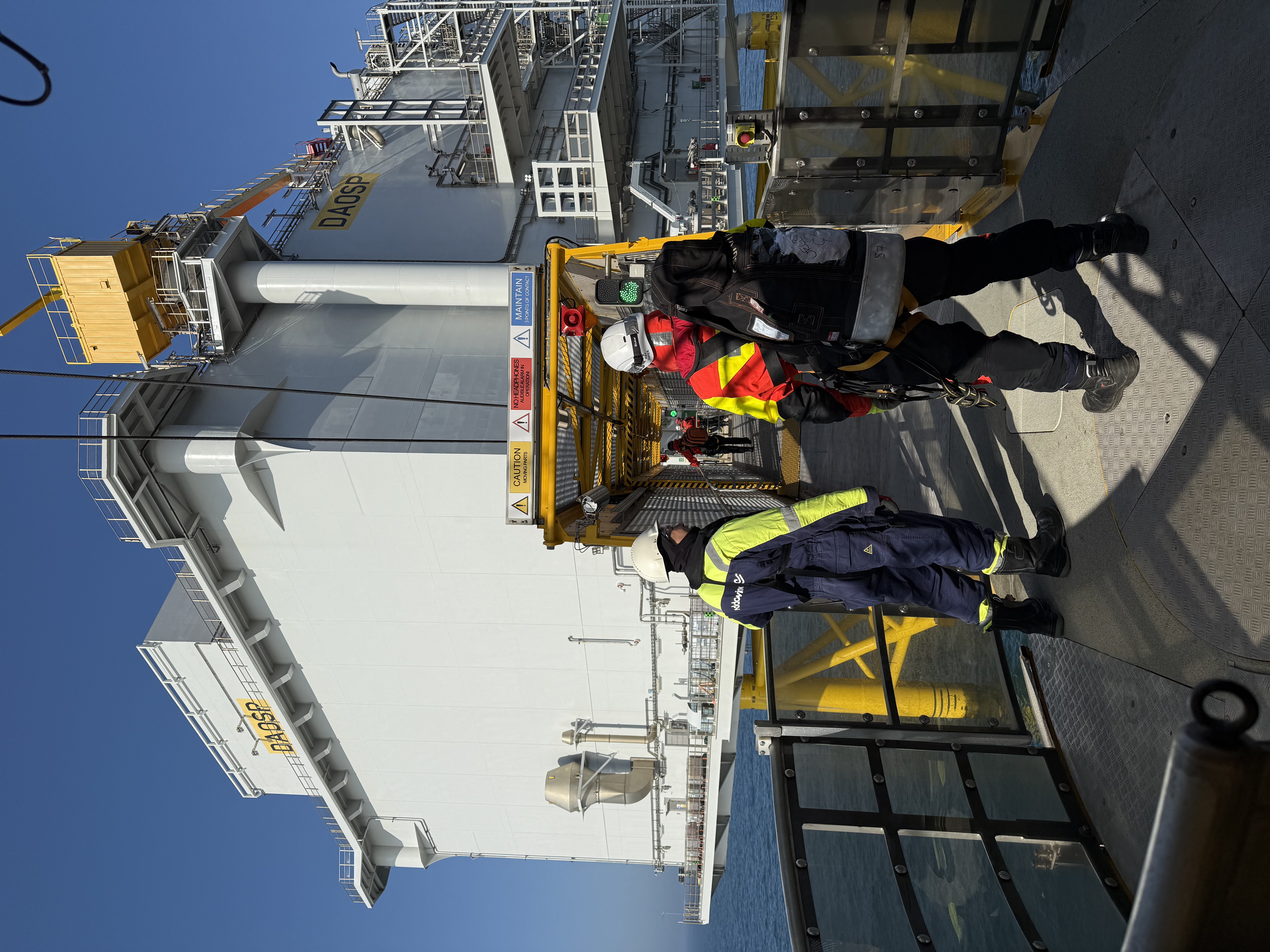

· Scenario B: Far-Offshore Wind Farm (50+ km out). At this distance, daily commuting is impractical or unsafe due to travel time and weather. Crews live offshore for a week or two at a time on a Service Operations Vessel (SOV) or an accommodation platform stationed near the turbines. Here, a “day” at work is actually 24 hours at sea. A technician might finish the day’s tasks, shower, eat, and then spend the evening in a lounge or their cabin on the vessel – still surrounded by coworkers and the constant reminder of being at work. Contact with family is limited to video calls (dependent on the satellite internet functioning). There is no going home until the rotation ends. Off time and on time blur together. As one offshore worker described, “it’s like you never really leave the job site – you’re always half-working, half-resting, but never fully relaxed.” The longer the stint, the more this wears on the psyche. Small stresses can compound; a minor disagreement with a coworker or a skipped call with family due to connection issues can loom large when you’re stuck in the middle of the sea. After 14 days, some crew describe a sense of detachment not only from home, but even from reality – an “offshore bubble” effect where life on land starts to feel distant or surreal.

From a human factors standpoint, Scenario B carries far greater risk for sustained stress and burnout. A key reason is the absence of recovery opportunities. In Scenario A, each evening provides a chance to mentally recover; in Scenario B, recovery must happen in the same environment as work, which research shows is far less effective. Moreover, social isolation is inherently higher in far-offshore assignments. Being able to see the shore (or even knowing it’s a short trip away) has a huge psychological impact. Near-shore crews know that if an emergency at home occurs, they’re at most an hour or two away from land. Far-offshore crews know that if something happens – a family crisis, personal health issue – home is a helicopter flight away, weather permitting. That constant background knowledge creates underlying anxiety that never quite disappears. Indeed, surveys show that offshore workers list “being away from family for weeks” as one of the hardest parts of the job.

To put numbers to it, consider offshore rotation schedules across different distances. In the UK and German sectors, a common practice now is a 14-day on/14-day off rotation for far-offshore wind farms (similar to oil & gas). Closer to shore, some projects have experimented with 7 days on/7 off, or even weekday-on, weekend-off patterns when feasible, to improve work-life balance. It’s telling that when asked about their needs, 30% of offshore wind farm employees surveyed in 2023 said their top concern was better work-life balance support. That is, nearly a third of workers explicitly feel the need for help in balancing the intense time away with their personal life. This need was on par with demands for better physical provisions like healthy food and exercise facilities offshore. Furthermore, 23% of workers said they want to connect with family more often while offshore, underscoring how distance literally and figuratively strains family ties. By contrast, in jobs where workers return home daily, you wouldn’t see a quarter of employees pleading for basic family contact – it’s taken for granted.

The differences between near and far offshore working conditions are not just anecdotal – they represent distinct risk profiles. Closer installations let companies treat operations almost like onshore projects in terms of personnel logistics and wellbeing. Farther installations start to resemble the oil & gas model, with all its accompanying human factor challenges. As Europe and the Middle East push wind farms farther out to sea (e.g. into the North Sea or Arabian Gulf), the industry must recognize that it is entering a new era for workforce mental health. The isolation equation will only intensify unless proactive measures are taken.

The Unseen Crisis: Are Wind Farm Companies Prepared?

The offshore wind industry has prided itself on strong safety performance and technical excellence. However, when it comes to mental health and long-term wellbeing, most wind farm companies today are playing catch-up. The notion that psychological health deserves equal footing with physical safety is still relatively new in this sector. Many companies simply do not have robust mental health strategies tailored for remote operations – a gap that could have serious consequences as projects and distances scale up.

One reason for the unpreparedness is historical. Offshore wind grew out of the onshore wind and maritime industries, which historically haven’t faced the extreme rotations of offshore oil. Physical safety (PPE, procedures, fall protection) has understandably been the focus during the rapid build-out of wind farms. But psychological safety? That has often been relegated to a footnote, if acknowledged at all. In high-risk industries, there’s a cultural legacy of toughness – the idea that if you can’t handle the stress, you don’t belong out there. Such attitudes have long impeded honest conversations about mental health. In oil and gas, for example, the culture of not admitting to personal struggles meant issues stayed hidden; it took alarming metrics (like a doubling of suicide rates) to jolt the industry into action. Offshore wind may be on a similar trajectory if it doesn’t heed those lessons. A 2024 benchmark study of UK businesses found that over half of large employers were failing to support workers’ mental health adequately, often due to a lack of expertise or resources. It’s likely that many wind energy firms would fall into this category as well, given that formal mental health programs specific to offshore crews are still rare.

Alarm bells are already ringing. Occupational stress risk in offshore wind is now getting attention from industry groups – for instance, the G+ Offshore Wind Health and Safety Organization recently launched a project to assess stress and mental wellbeing risks across the sector. This came on the heels of anecdotes about rising fatigue and turnover on some North Sea wind farms, and internal surveys where employees voiced concerns about burnout. In one internal company survey shared at a 2023 conference, two-thirds of technicians reported experiencing symptoms of poor mental health during lengthy offshore deployments (e.g. prolonged sadness, anxiety, or irritability), yet a majority had never used any employee counseling or support service (often because they didn’t know it existed or feared stigma). These datapoints echo a Gulf-region study in oil & gas where 66% of workers reported poor mental health symptoms and 33% showed clinical burnout signs during long rotations. Simply put, a substantial portion of the offshore workforce may be silently struggling at any given time – a reality that remains “invisible” when companies only track accident rates or equipment downtime.

The cost of ignoring this issue can be very steep. Unaddressed mental health problems can lead to accidents, as discussed, but also to operational inefficiencies and loss of talent. Stressed or distracted workers are more prone to mistakes – a safety liability. Productivity suffers when crews are not at their mental best; jobs take longer and error rates climb. There is also the churn factor: employees who burn out will quit, and the industry could lose experienced talent just when it needs to ramp up. The oil industry discovered that poor mental health was costing an estimated $200 billion per year in lost productivity and turnover. Wind may not have such figures calculated yet, but even on a smaller scale, the business case for intervention is evident. Retention of skilled technicians is becoming a challenge as the demand for them grows worldwide. If word gets around that offshore wind jobs come with undue psychological toll and little support, recruits will think twice about signing up – or staying long-term.

Encouragingly, some wind companies are beginning to take action. A few European developers have started incorporating mental health awareness into their safety training, acknowledging that a “safe” worker is not just one who wears a harness, but one who feels psychologically supported. There’s movement at the corporate level too: progressive firms are establishing corporate wellbeing programs that include regular mental health check-ins for offshore staff, resilience training, and rotations designed with wellbeing in mind. Still, these are the exceptions that prove the rule. In practice, when deadlines are tight and vessels are booked, the default is often to push the crew to get the job done and assume they’ll cope. That mindset must change. The human factors revolution in offshore wind demands that we treat mental health as a core component of operational readiness – not an afterthought.

Turning the Tide: Solutions for Wellbeing and Efficiency

If distance from shore multiplies mental health risks, then we need to multiply our countermeasures as well. The good news is that there are concrete, actionable solutions that wind farm companies can implement to safeguard their workers’ wellbeing while maintaining (or even improving) operational efficiency. Forward-thinking companies in Europe are already piloting some of these approaches, and they can be adapted in the Middle East as the region develops its offshore wind potential. Here’s a blueprint for tackling the isolation equation:

· Optimize Rotation Schedules for Recovery: Re-examine the length and pattern of offshore rotations. The goal should be to minimize consecutive weeks offshore whenever feasible without compromising maintenance schedules. For instance, instead of defaulting to a 3-week-on, 3-week-off cycle to cover far-flung sites, companies can stick to 2 weeks on, 2 weeks off and use staggered crews or additional personnel to cover the extra crew change logistics. Research shows that shorter rotations (1–2 weeks) yield higher worker satisfaction and lower distress than 3-week hitches. If a longer rotation is unavoidable (due to weather windows or fewer transport opportunities in a remote project), consider granting extended shore leave afterward (e.g. 3 or 4 weeks off) to allow full recovery. Some Norwegian operators do 2 weeks on, 3 weeks off – effectively giving more rest than work days – and have found it sustains performance and morale better in the long run. The bottom line: design rotations not just for operational coverage, but for human sustainability.

· Enhance Onsite Living Conditions: Small quality-of-life improvements offshore can yield big mental health dividends. As the Sodexo survey highlighted, workers crave things like healthy food options, fitness resources, and quiet spaces to decompress. Wind farm operators should ensure that SOVs and platforms are equipped with wellness facilities – even modest gyms, comfortable lounge areas, and perhaps a dedicated quiet room or reading room. Good nutrition and the ability to exercise aren’t luxuries; they directly combat fatigue and boost mood. Some vessels now have Wi-Fi strong enough for video calls – investing in robust connectivity is crucial so that technicians can speak to their families regularly (and not just a scratchy 5-minute call). These measures signal to workers that their well-being is valued, which in itself improves morale.

· Mental Health Workshops and Training: Just as we conduct safety drills, we should be holding mental health workshops for offshore crews. These can be brief, interactive sessions (either during onshore breaks or even via teleconference offshore) that educate workers about stress management, coping strategies, and signs of mental strain. The aim is to normalize conversations about mental health and equip workers with tools to support themselves and each other. For example, a workshop might teach simple mindfulness techniques to manage anxiety, or tips on maintaining a healthy sleep routine offshore. There is evidence that when workers feel empowered with coping strategies and know that the company cares, it builds resilience. Additionally, training managers and supervisorsin mental health first aid is vital. Offshore installation managers should be able to recognize when a crew member is struggling (e.g. withdrawal, irritability, excessive fatigue) and know how to respond supportively. Leadership from the top is key here: when executives and managers openly discuss the importance of mental well-being – “It’s okay not to be okay” – it chips away at stigma and creates a culture where seeking help is seen as smart, not weak.

· Structured Peer Support and Counseling: Isolation is toughest when one feels alone in their experience. Companies can set up peer support networks so that workers have a go-to colleague (onboard “buddy” systems or onshore/offshore pairings) to talk to during difficult times. Sometimes just having someone to vent to who understands the life can prevent small issues from snowballing. In addition, confidential counseling services should be made easily accessible – for instance, a 24/7 helpline that offshore workers can call (via satellite phone or internet) to speak with a counselor about any stress, whether work-related or personal. Several operators now partner with employee assistance programs that have specific experience with remote workers. Importantly, make sure everyone knows these resources exist and actively encourage their use. One idea is to incorporate a quick well-being check at the end of daily toolbox talks or safety meetings – e.g. reminding the crew “If you’re feeling overly stressed or down, it’s important to talk to someone – we have support available.” Such gestures can surface issues early and prevent tragedies.

· Design Work to Reduce Isolation: At an industry level, innovation in how we deploy and rotate staff could mitigate isolation. For example, instead of keeping the exact same group of 20 people together on a platform for two weeks (which can amplify tensions in a small social bubble), some companies rotate a few individuals out at mid-hitch and replace them with others for cross-pollination and a psychological break. Another approach is exploring hybrid deployment models where possible – e.g. using helicopters to swap out teams more frequently in far-offshore sites, or building offshore accommodation platforms that are more spacious and less industrial in feel (almost like a remote campus). Drones and remote monitoring tech might reduce how many people need to be out there and for how long. Every reduction in perceived isolation counts.

· Integrate Wellbeing into KPIs: Finally, companies should treat mental health as a key performance indicator, just like equipment uptime or safety incident rates. This means tracking metrics such as fatigue levels, overtime hours, reported mental health concerns, and crew turnover rates. Regular anonymous surveys can gauge stress and job satisfaction levels among offshore staff. By measuring these, management can catch negative trends early. Perhaps rotation lengths need adjusting if stress scores are spiking, or a particular wind farm site might need an intervention if its crew reports consistently poorer morale than others. Tying manager evaluations in part to team well-being metrics can also incentivize a greater focus on these issues. The adage “you manage what you measure” holds true – making mental well-being a visible priority in reports and meetings cements its importance.

It’s worth noting that supporting mental health isn’t just altruism – it pays off in performance. A mentally healthy crew is more alert, more creative in problem-solving, and less likely to suffer the kind of human-error incidents that cause costly downtime. For offshore wind companies operating in high-risk, high-reliability environments, this is a direct contributor to operational excellence. And from the workers’ perspective, knowing their employer has their back builds loyalty. Technicians who feel valued and supported are far more likely to stay with the company, reducing attrition in a competitive labor market.

Conclusion: Closing the Distance Gap

Offshore wind’s future is undeniably exciting – turbines will grow larger, projects will venture further into the deep sea, and new markets (from the North Sea to the Middle East) will come online. But as we extend our reach, we must not leave the human element behind. The isolation equation – the multiplying effect of distance on mental health risks – is a critical challenge of this next frontier. Ignoring it would be a grave mistake, both ethically and operationally. History has shown in other sectors that failing to address workers’ psychological needs leads to accidents, inefficiencies, and human costs that no company should be willing to bear.

The time is now for a Human Factors Revolution in offshore wind, one that fully integrates mental well-being into the fabric of project planning and safety management. European companies can share lessons with their Middle Eastern counterparts to get ahead of the curve, ensuring that as wind farms scale up, so do the support systems for crews. By implementing smarter rotation schedules, investing in onboard quality of life, providing mental health training and resources, and fostering an open, supportive culture, wind farm companies can turn distance from shore into just a logistical challenge, not a human crisis.

Ultimately, caring for the people who work in extreme environments is not a cost, but an investment. When offshore workers feel supported, they perform better and more safely. They become long-term stewards of the industry rather than burnout statistics. As one seasoned technician put it, “Give us the tools to take care of ourselves out there, and we’ll take care of your turbines – and come back ready for more.” It’s time to bridge the gap between the wind farm and the shore, not with shorter distances, but with stronger human connections. In doing so, the offshore wind sector can truly go “beyond the hard hat,” building a legacy of sustainable energy delivered by a resilient, healthy, and thriving workforce.

References

Alroomi, A. H., & Mohamed, S. (2021). Impact of occupational stressors on safety behavior and accidents in remote oilfield operations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 7823. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph18157823

Cooper, C. L., & Sutherland, V. J. (1987). Job stress, mental health and accidents among offshore workers in the oil and gas extraction industry. Journal of Occupational Medicine, 29(2), 119-125. DOI: 10.1097/00043764-198702000-00010

Mette, J., Velasco Garrido, M., Harth, V., Preisser, A. M., & Mache, S. (2018a). Healthy offshore workforce? A qualitative study on offshore wind employees’ occupational strain, health, and coping. BMC Public Health, 18(172), 1–12. DOI: 10.1186/s12889-018-5079-4 https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-018-5079-4#:~:text=Workers%20generally%20reported%20good%20mental,related%20to%20seeking%20social%20support

Mette, J., Velasco Garrido, M., Preisser, A. M., Harth, V., & Mache, S. (2018b). Linking quantitative demands to offshore wind workers’ stress: Do personal and job resources matter? BMC Public Health, 18(934), 1–9. DOI: 10.1186/s12889-018-5808-8 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329035887_Sleep_quality_of_offshore_wind_farm_workers_in_the_German_exclusive_economic_zone_a_cross-sectional_study#:~:text=needs%20for%20recovery,in%20the%20offshore%20wind%20industry

Parkes, K. R. (1998). Psychosocial aspects of stress, health and safety on North Sea oil and gas installations. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 24(5), 321–333. PMID: 9916829 (Discusses impacts of extending offshore tours) https://www.sjweh.fi/download.php?abstract_id=352&file_nro=1#:~:text=Most%20offshore%20personnel%20work%20rotas,3%20rotas%20%283

Parkes, K. R., Fruhen, L. S., & Parker, S. K. (2022). Direct, indirect, and moderated paths linking work schedules to psychological distress among fly-in, fly-out workers. Work & Stress, 36(4), 351–374. DOI: 10.1080/02678373.2021.1898631 https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Main-categories-for-offshore-employees-working-conditions_fig1_321689618#:~:text=Fly,for%20significant%20variance%20in%20psychological

Velasco Garrido, M., Mette, J., Mache, S., Harth, V., & Preisser, A. M. (2018). Sleep quality of offshore wind farm workers in the German exclusive economic zone: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 8(11), e024006. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024006 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329035887_Sleep_quality_of_offshore_wind_farm_workers_in_the_German_exclusive_economic_zone_a_cross-sectional_study#:~:text=with%20sleep%20onset%20was%20reported,Conclusions%20Workers%20in

Sodexo. (2024, January 19). Survey Reveals What Workers Need to Thrive at Offshore Wind Farms. Sodexo Energy & Resources Blog. https://us.sodexo.com/inspired-thinking/energy-and-resources/blogs/survey-reveals-what-workers-need