The 4X factor: why wind workers are four times more likely to get hurt?

Part 2 of The Wake‑Up Series: Urgent Action Required to Tackle the Escalating Offshore Wind Safety Crisis

The global wind industry is experiencing explosive growth, bringing a surge of new workers into the field. There are currently about 1.2 million people employed in the wind industry worldwide, and projections show 3.3 million new wind energy jobs could be created over the next five years (Global Wind Energy Council [GWEC], 2021). This rapid expansion is exciting for renewable energy, but it also introduces a serious challenge: many of these workers are new to wind and lack industry-specific experience. Early evidence suggests that this inexperience comes with a “4X factor” in safety risk – in other words, wind workers with limited experience are four times more likely to get hurt on the job than their seasoned counterparts. The convergence of a green jobs boom with an inexperienced workforce is creating a perfect storm of safety concerns that demands urgent attention.

The Inexperience Problem: New Workers at Higher Risk

Multiple studies have found that new and inexperienced workers face dramatically higher odds of workplace accidents. For example, an analysis of 12 years of workplace accident data by the Health and Safety Authority in Ireland concluded that workers are four times more likely to suffer an accident in the first six months of a new job (Health and Safety Authority, 2016). The reasons are intuitive: newcomers often have inadequate training and supervision, less familiarity with hazards, and may be reluctant to question instructions – all factors that elevate risk (Health and Safety Authority, 2016). In high-hazard industries like wind energy, this risk is even more pronounced. A similar pattern has been observed in U.S. occupational safety data, where first-year employees are far more likely to be injured than those with longer tenure (Simplified Safety, n.d.). The wind sector’s workforce expansion means thousands of first-year employees are entering turbine sites, and each is statistically at greater risk of injury simply due to lack of experience and task-specific knowledge.

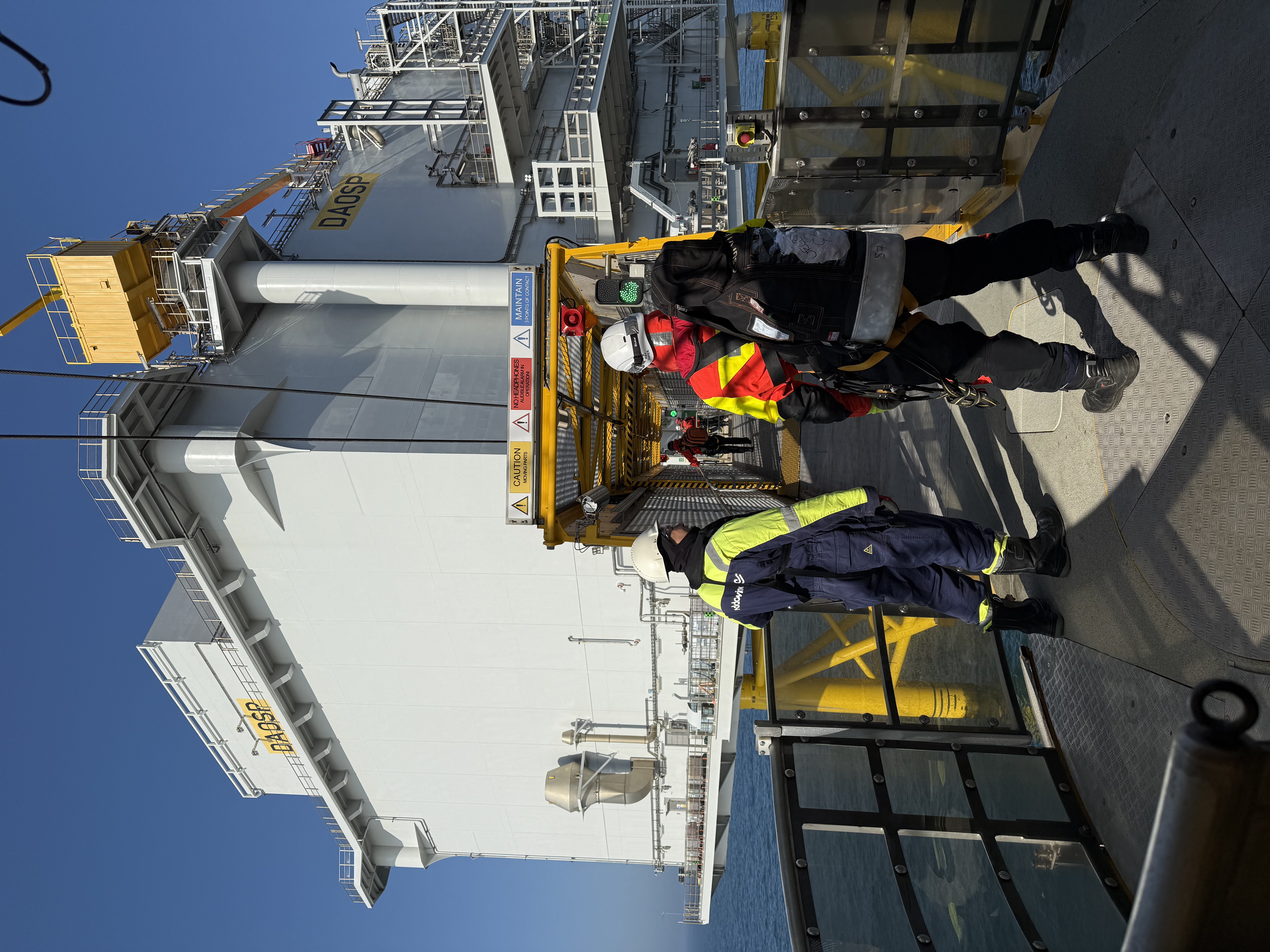

Wind energy jobs also tend to be inherently hazardous, which amplifies the importance of experience. Whether constructing massive turbine components or servicing equipment atop 100-meter towers, wind workers face many of the same dangers found in construction, electrical utility, and maritime industries combined. They work at great heights, often in harsh weather, and around heavy machinery and high-voltage systems. A wind technician scaling a tower or a crew assembling turbine blades must contend with fall hazards, powerful electrical currents, and large moving parts on a routine basis. Even seemingly straightforward tasks can carry deadly risks – wind techs are at risk of arc flash burns, fires, electrocution, and even explosions, especially if proper lockout-tagout procedures aren’t rigorously followed (Arnold & Itkin LLP, n.d.). These conditions mean that when new, untrained workers enter the wind industry, the margin for error is slim. The combination of inexperience and extreme work conditions is at the heart of the “4X factor” in wind worker injuries.

A Safety Record That Lags Behind

Compounding the workforce experience gap is the sobering reality that, by the numbers, the wind industry’s safety performance lags behind that of comparable sectors. A recent academic study by researchers at the University of Strathclyde highlighted this disparity. The study, published in 2024, reviewed offshore wind operations globally and found that injury rates for offshore wind workers are up to four times higher than for offshore oil and gas workers (Rowell, McMillan, & Carroll, 2024). In other words, even after adjusting for hours worked, offshore wind has a worker injury frequency roughly 3–4 times worse than the well-established oil and gas industry (Rowell et al., 2024). This is a startling statistic, given that oil and gas has long been considered hazardous; it suggests that wind has significant room for improvement in safety practices, possibly due to its newer status and evolving regulations.

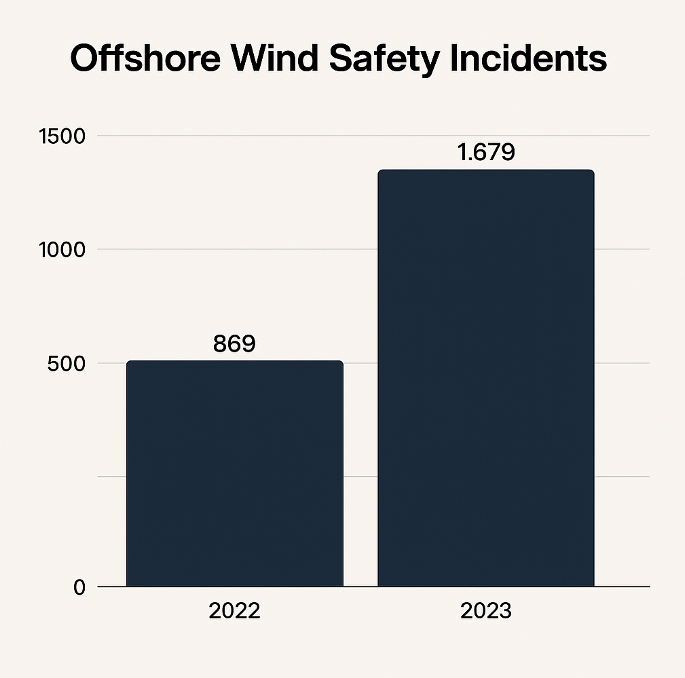

Real-world incident data further illustrate the safety challenges in wind. Industry safety reports show that the number of accidents in wind is rising as the sector expands. According to the Global Offshore Wind Health & Safety Organisation (G+), which tracks safety incidents among major wind farm developers, the global offshore wind sector recorded 1,679 safety incidents in 2023, nearly double the 867 incidents reported in 2022 – a 94% year-on-year increase (G+ Global Offshore Wind Health & Safety Organisation, 2024). This sharp uptick in total incidents (see figure below) is partly attributable to the surge in hours worked as new projects come online, but it is nonetheless a cause for concern. More activity has unfortunately meant more opportunities for things to go wrong, and the data reflect that troubling reality.

Drilling down into the types of incidents, certain high-risk activities stand out. The G+ 2023 report indicates that some work processes consistently account for a large share of the accidents. In particular, lifting operations (e.g., using cranes and hoists to install or maintain turbine components) were the single largest category of incidents in 2023, contributing on the order of a couple hundred events. Vessel operations – the marine transport of crews and equipment to offshore turbines – were another major source of incidents, reflecting the dangerous marine environment in offshore wind. Routine maintenance tasks and inspections also saw a significant number of injuries and near-misses, underscoring that even day-to-day operations carry risk (G+ Global Offshore Wind H&S Organisation, 2024). The bar chart below summarizes the top work processes associated with incidents last year. These patterns show where safety interventions are most needed: for example, better lift planning and crane operator training, improved marine safety protocols, and meticulous maintenance procedures can potentially mitigate the most common accident causes.

Several positive notes can be found in the data: the industry’s safety metrics, such as Total Recordable Injury Rate (TRIR) and Lost Time Injury Frequency, have, in fact, remained relatively stable over recent years even as raw incident counts grew (Energy Institute, 2024). This suggests that when accounting for the huge increase in hours worked, the rate of injuries per hour has not worsened drastically – a testament to ongoing safety efforts. Additionally, G+ reported that the proportion of high-potential incidents (events that could easily have led to serious injury or fatality) actually fell by more than half in 2023, down to 11% of all incidents, indicating some success in preventing the most catastrophic accidents (Energy Institute, 2024). However, the overall picture is still mixed at best. The wind industry’s safety performance is far from “zero harm”, and it trails the benchmarks set by older industries. Recognizing this gap is important: it means wind can learn from those sectors (like oil and gas) that have decades of experience building rigorous safety cultures and regulatory frameworks. Indeed, experts have suggested that regulators consider implementing industry-specific safety legislation for wind, analogous to the rules in oil and gas, to address the unique risks of offshore projects (Rowell et al., 2024). Wind energy is charting new territory, and in many ways, its safety standards and oversight need to catch up with its growth.

The Hidden Costs of Accidents

Beyond the human toll of injuries, wind companies and workers face immense financial and operational costs when accidents occur. Workplace incidents carry direct costs, such as medical treatment, emergency response, equipment damage, and lost work time, as well as often much larger indirect costs, such as project delays, legal liabilities, regulatory fines, and reputational damage. For employers, a single serious accident can be devastating to the bottom line. According to National Safety Council data, the average cost of a medically consulted work injury in 2023 was about $43,000, and the average cost of a single work-related fatality was approximately $1.46 million (National Safety Council, 2023). Wind farm accidents can easily exceed those averages. For instance, when a large crane tipped over during the construction of a wind turbine, it resulted in roughly $1.2 million in property damage (Gray-Duffy LLP, 2013). If a worker is severely injured, settlements or judgments can run into the high six or seven figures, as seen in various wind industry injury cases. In European projects, it’s not uncommon to hear of injury claims exceeding €1 million for life-altering harm – a figure in line with the NSC’s estimate for a loss of life in the U.S.

The indirect costs are especially problematic in the wind industry, where project timelines are long and tightly orchestrated. An unexpected accident can halt a construction or maintenance operation, leading to costly downtime. One industry survey found that across the energy and industrial sectors, unscheduled downtime costs businesses on average about $125,000 per hour (West, 2023). For an offshore wind installation, the costs can be even higher due to the complexity and scale of operations, on the order of $180,000 in lost revenue per hour of downtime in some estimates. If a major accident forces a project to stop for days or weeks, the accumulated losses from idle equipment, contract penalties, and schedule overruns can dwarf the direct costs of the accident itself. There are also harder-to-measure costs: morale and productivity declineamong a workforce after a colleague’s injury, and a company’s safety reputation (crucial for winning contracts and regulatory goodwill) can suffer after high-profile incidents. All of these factors reinforce that investing in safety is not just an ethical duty but also a sound financial decision for wind energy companies. As one safety adage puts it, “If you think safety is expensive, try an accident.” In wind, accidents are indeed enormously expensive – far more so than the preventative measures that could avoid them.

Building a Safer Wind Industry

Given these challenges, how can the wind industry reduce the 4X injury factor and protect its workforce? A central solution is training and competency development on a massive scale. As wind projects proliferate, companies must ensure that new hires receive thorough safety education before ever setting foot on a turbine site. This includes not only general safety training but also wind-specific certifications (for example, the Global Wind Organisation’s Basic Safety Training modules) that cover the unique hazards of turbine environments. Hands-on apprenticeships and mentoring programs can bridge the experience gap; pairing novice technicians with seasoned veterans for the first several months can dramatically improve situational awareness and safe work practices. Some industry leaders have already adopted this approach. For instance, one major turbine manufacturer requires all new technicians to complete a multi-week training academy and then work under a mentor for six months in the field – measures aimed at ensuring that no one’s “first day” on the job is truly their first exposure to the job. Such programs echo the HSA’s recommendation that employers provide intensive supervision and coaching to every new recruit(Health and Safety Authority, 2016). The goal is to give new wind workers the knowledge and confidence to spot hazards and speak up – effectively neutralizing the inexperience penalty.

Another critical piece is strengthening safety culture and leadership across all levels of wind organizations. Safety can’t be just a checklist or a compliance obligation; it has to be a core value that is visibly championed by management and embraced by workers. In practice, this means empowering any worker, even the most junior technician, to halt a task if something seems unsafe, without fear of retribution. It also means actively learning from near-misses and past incidents: the data on frequent accident types (like lifting operations or vessel transfers) should be continuously analyzed and used to improve procedures and engineering controls. For example, if lifting operations are a top incident category, companies might invest in newer crane technology, better lift planning protocols, or additional crew training in rigging and signaling. Industry-wide, sharing of best practices through forums like G+ is essential so that lessons learned by one company can benefit all. The wind industry has also begun developing standardized safety rules – G+ has promulgated a set of “Life-Saving Rules” tailored to offshore wind work, which provide a common baseline for safe behaviors regardless of employer (G+ Global Offshore Wind H&S Organisation, 2024). Adhering to and promoting these rules can help instill a consistent safety mindset, even as workers move between different projects and contractors.

Finally, there is a policy dimension. Regulators and industry bodies should acknowledge that the safety framework for wind power is still maturing and take proactive steps to support it. This could involve crafting regulations specific to wind farm construction and maintenance (as suggested by Rowell et al. (2024)), rather than relying on general construction or maritime safety rules. It could also mean increased funding for research into wind farm safety solutions – for instance, improved fall protection systems for turbine towers, or better remote monitoring to reduce the need for hazardous maintenance tasks. Governments, developers, and educational institutions can collaborate to expand the pipeline of qualified wind workers, ensuring that safety training is embedded in skill-building from the start. Given that the world is betting on wind power as a cornerstone of the clean energy transition, it is in everyone’s interest – public and private alike – to make wind jobs as safe as possible. A sustainable industry is one where workers can return home unharmed every day.

Conclusion

The “4X factor,” highlighting wind energy’s injury problem, is a clear warning sign. It tells us that without concerted action, the rapid growth of wind power could be marred by an unacceptable rate of worker injuries. However, it is also a call to action. The factors driving the higher risk – an influx of new workers, unique operational hazards, and evolving safety regimes – are challenges that can be overcome. The wind industry has the advantage of being forward-looking and innovative by nature; these same qualities should be applied to safety. By investing in robust training, sharing knowledge, enforcing high standards, and continuously improving safety technology and practices, wind companies can defuse the 4X risk factor. The ultimate vision is to ensure that green energy jobs are “good jobs” in every sense, including safety. Wind power’s promise is not only to deliver clean electricity, but to do so with a workforce that is protected and empowered. Achieving that will require commitment from all stakeholders – industry leaders, workers, and regulators – to put safety at the forefront. In the long run, there is no trade-off between safety and success in wind energy; instead, a strong safety culture is essential to sustaining the industry’s growth. As the saying goes, we must build the wind energy future “safe by design, and safe by practice”, so that the only thing soaring high is the turbines, not the injury statistics.

References

Arnold & Itkin LLP. (n.d.). Dangers on the Job for Wind Energy Workers. Retrieved from https://www.arnolditkin.com/blog/work-accidents/dangers-on-the-job-for-wind-energy-workers/

Energy Institute. (2024, June 19). Offshore wind safety performance mixed, while record 61.9 million hours worked [News article]. Energy Knowledge. Retrieved from https://knowledge.energyinst.org/new-energy-world/article?id=138870

G+ Global Offshore Wind Health & Safety Organisation. (2024). 2023 Incident Data Report. Retrieved from https://www.gplusoffshorewind.com/work-programme (Data summarized by Energy Institute, 2024)

Global Wind Energy Council. (2021, April 30). Wind can power 3.3 million new jobs worldwide over next five years [Press release]. Retrieved from https://gwec.net/wind-can-power-3-3-million-new-jobs-worldwide-over-next-five-years/

Gray-Duffy LLP. (2013, September). Aggressive negotiations lead to a $295,000 settlement in crane accident at wind farm for damages of approximately $1.2 million [Case result]. Retrieved from https://grayduffylaw.com/2013/09/gray-duffys-aggressive-negotiations-lead-to-a-295000-settlement-in-crane-accident-at-wind-farm-for-damages-of-approximately-1-2-million/

Health and Safety Authority. (2016, March 11). New workers four times more likely to have an accident[Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.hsa.ie/eng/news_events_media/press_releases_2016/new_workers_four_times_more_likely_to_have_an_accident.html

National Safety Council. (2023). Work Injury Costs. Injury Facts. Retrieved from https://injuryfacts.nsc.org/work/costs/work-injury-costs/

Rowell, D., McMillan, D., & Carroll, J. (2024). Offshore wind H&S: A review and analysis. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 189, 113928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.113928

Simplified Safety. (n.d.). The risks with new employees and what to do about them. Retrieved from https://simplifiedsafety.com/blog/risks-of-being-new-employee/

West, P. (2023, December 1). Did you know that unplanned downtime costs $125,000 per hour? IoT Insider. Retrieved from https://www.iotinsider.com/industries/industrial/did-you-know-that-unplanned-downtime-costs-125000-per-hour/