From command to care: redefining safety leadership in extreme environments

Part 1 of the Leadership Awakening Series

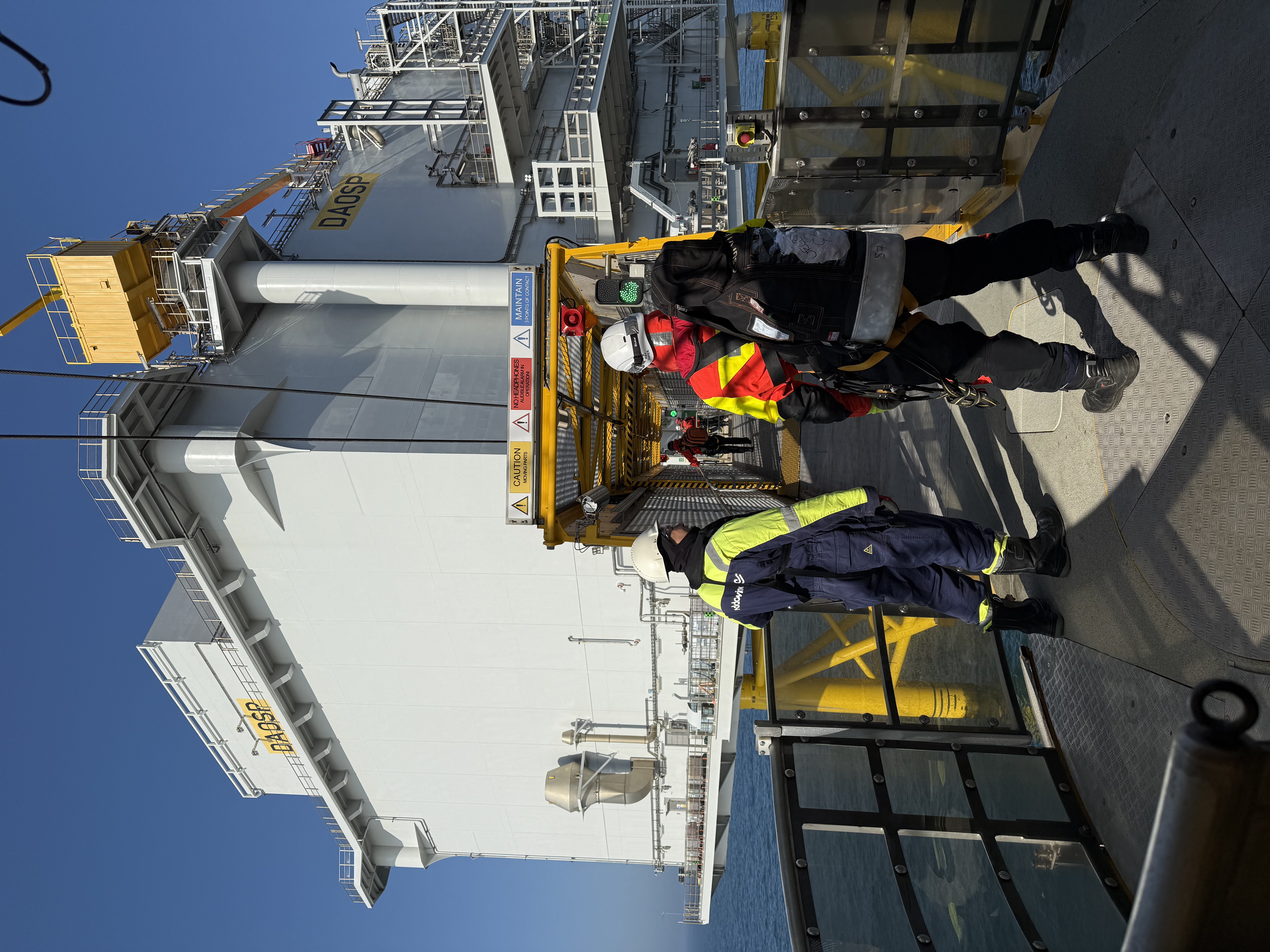

The wind energy sector, much like oil and gas before it, was built on a culture of toughness and stoicism. In the early days, a “tough it out” mentality was often seen as a virtue – workers endured harsh conditions without complaint, and leaders were expected to be hard-driving taskmasters. Yet this very mentality has become a paradoxical liability for today’s organizations. Emerging evidence shows that the macho, command-and-control approach to safety now threatens the future workforce it aims to protect. Younger generations of workers demand more supportive, psychologically safe workplaces, and high-risk industries that fail to adapt risk driving away talent and jeopardizing safety performance (Daigneault, 2024). In other words, what got these industries here won’t get them much further – command must give way to care. This post, part of the Leadership Awakening Series, challenges traditional safety leadership norms and presents a data-driven case for a transformational shift from command to care in extreme environments like offshore wind energy.

The Human Cost of “Tough It Out” Culture

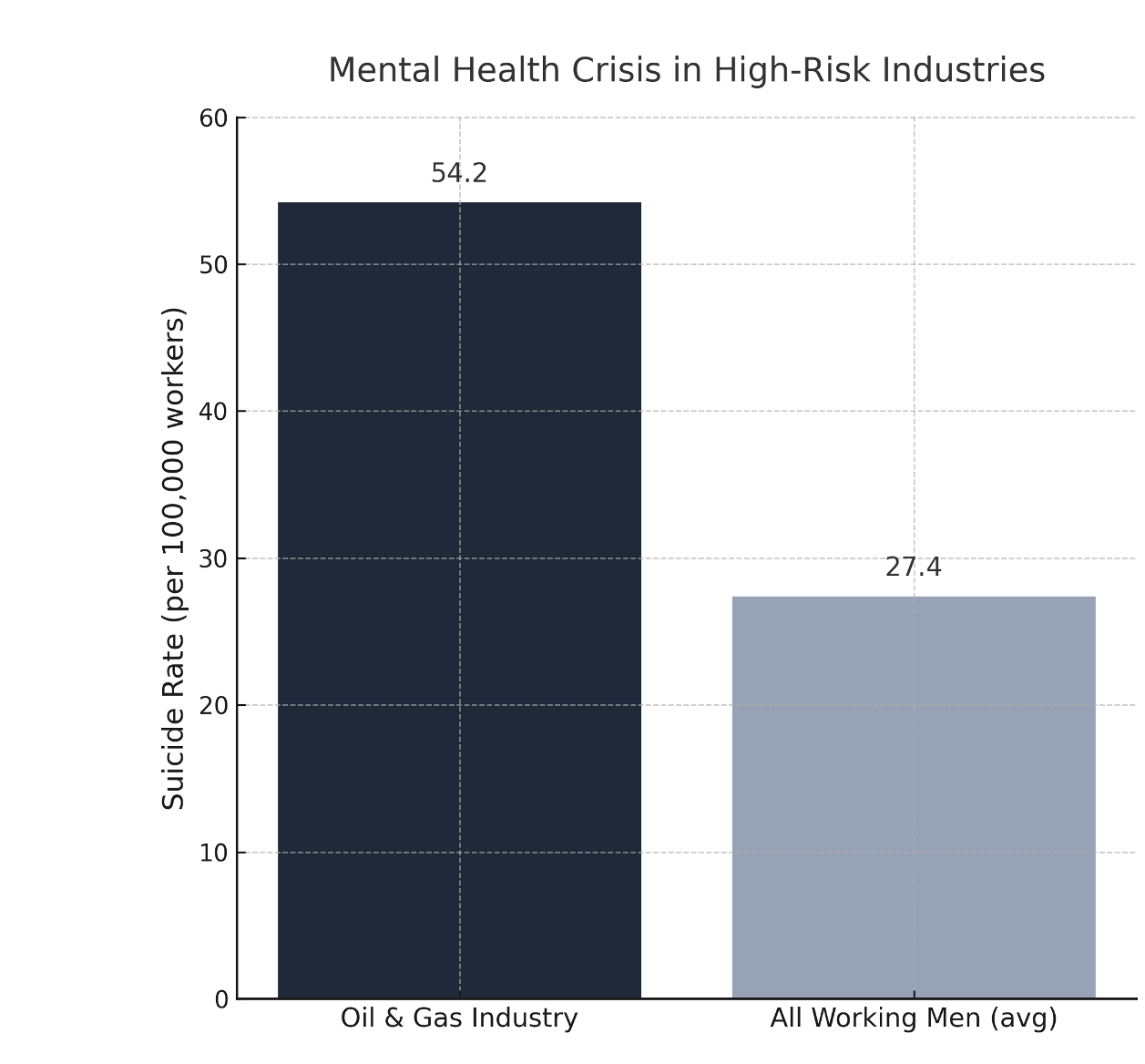

Decades of “safety by authority” have yielded lessons written in blood. High-hazard sectors have seen that a rigid, fear-based culture can backfire, leading to underreported hazards, burnout, and even tragic outcomes. For instance, the oil, gas, and mining industries – long dominated by hyper-masculine, stoic norms – consistently suffer the highest suicide rates of any occupational group. A recent U.S. CDC analysis found that male workers in extraction industries take their own lives at roughly twice the rate of the general working male population (Sussell et al., 2023; Joseph, 2020). The toll of this hidden mental health crisis vividly illustrates how a “tough it out” ethos inflicts harm. Workers in these extreme environments often internalize stress and trauma, fearing any admission of difficulty will be seen as weakness. In one harrowing account from a Gulf of Mexico oil platform, crews witnessed a fatal accident and were given only 15 minutes to mourn before being told to resume work – an attitude of emotional suppression that was typical of the era (Rosin, 2016 as cited in Ely & Meyerson, 2008). Such stories underscore that emotional silence on the job comes at a high price (Ely & Meyerson, 2008).

It’s not just mental health – an authoritarian culture also compromises physical safety. When workers fear being seen as complainers, they hesitate to speak up about hazards or fatigue. Studies show that new hires and contractors, eager to prove their toughness, often avoid voicing concerns; consequently, they suffer disproportionate injury rates. In one analysis, workers were four times more likely to have an accident within their first six months on a new job, largely due to inexperience and reluctance to ask questions (Health and Safety Authority, 2016). High-risk sectors like construction and offshore wind are especially vulnerable: a 2024 review found that offshore wind workers have injury frequencies up to 3–4 times higher than their counterparts in offshore oil and gas, despite oil and gas’ hazardous reputation (Rowell et al., 2024). This disparity suggests that the rapidly growing wind industry – often staffed by younger, less experienced workers – cannot simply import the old “tough guy” mindset of oil and gas without consequences. If anything, the data indicate that wind energy’s safety practices need urgent improvement to catch up with more mature industries (Rowell et al., 2024). The traditional bravado is thus not only outdated but actively dangerous: it drives mental distress, deters reporting of problems, and ultimately correlates with higher accident rates.

Modern executives are beginning to acknowledge this paradox. As one industry leader bluntly put it, “The ‘suck it up’ approach that built our industry is now breaking it.” The future workforce will not tolerate a workplace that treats burnout as a badge of honor or criticism as weakness. Millennials and Gen Z employees expect management to value mental, emotional, and social safety alongside physical safety (Daigneault, 2024). They are far more likely to leave employers who maintain a toxic or neglectful safety culture – one survey found that 12% of employees with low psychological safety planned to quit within a year, versus only 3% of those who felt safe (Boston Consulting Group, 2021). In short, clinging to a command-and-control, fear-based leadership style is not just bad for people – it’s bad for business. The very survival of high-risk industries in a competitive talent market depends on breaking the stigma and placing care for workers at the forefront of safety leadership.

From Compliance to Caring: Why Psychological Safety Is a Game-Changer

Forward-thinking organizations are pivoting from a narrow compliance mindset (“follow the rules or else”) to a culture of caring, where employees at all levels feel responsible for safety and free to speak up. At the heart of this culture shift is the concept of psychological safety – a shared belief that people will not be punished or humiliated for reporting mistakes, voicing concerns, or asking for help. Psychological safety is not a soft, feel-good notion; it is a proven driver of performance and accident prevention. Research in various sectors has shown that teams with high psychological safety are more effective, learn from errors, and have better safety outcomes (Edmondson, 2019). In high-risk environments, where front-line workers often spot the early signs of danger, the ability to raise a hand and yell “Stop!” without fear can literally save lives.

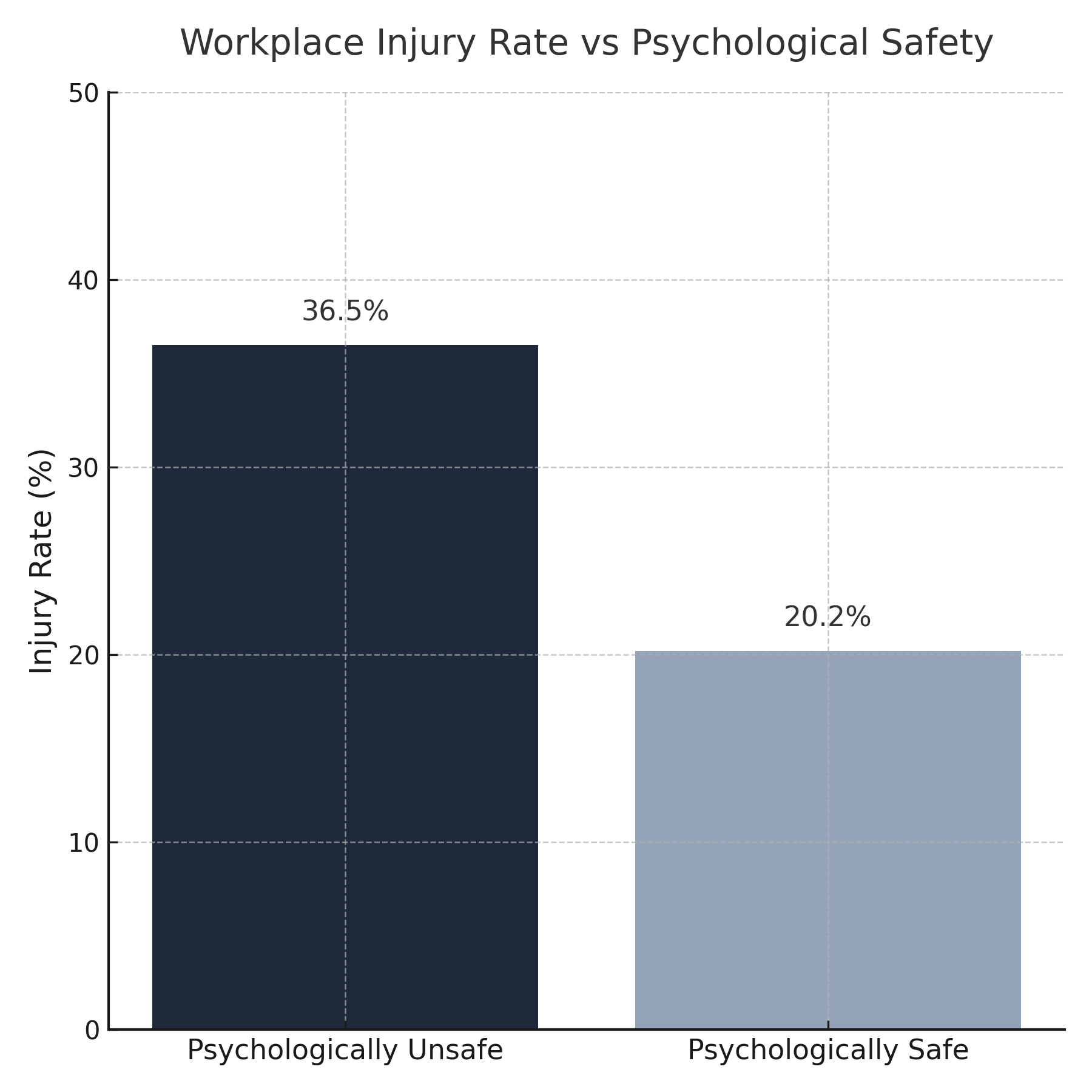

Crucially, psychological safety correlates with lower injury rates on the ground. A recent National Safety Council survey found that employees who feel psychologically unsafe report workplace injuries at nearly double the rate of those who feel safe (National Safety Council, 2023). This suggests that when people are afraid to speak or distracted by stress, the likelihood of accidents surges. Conversely, a trusting, open atmosphere reduces incidents – not just by encouraging hazard reporting, but by fostering engagement and vigilance. Workers who feel valued and heard are more invested in the job and more attentive to following procedures (Daigneault, 2024). They collaborate to solve problems instead of hiding them. In essence, a safe mind leads to safer behavior.

Building psychological safety starts with leadership behavior. Leaders set the tone by modeling vulnerability and openness: admitting their own fallibility, actively inviting input, and thanking employees for raising concerns. This contrasts sharply with the old-school “leader as infallible commander” image. Yet, evidence shows the humane approach works. Google’s famous internal study on team performance identified psychological safety as the number one differentiator between high-performing and low-performing teams (Rozovsky, 2015). Likewise, a McKinsey survey reported that only 26% of leaders in organizations worldwide are seen as creating psychological safety for their teams, indicating a huge opportunity for improvement (McKinsey & Company, 2021). Leaders who invest in trust-building can reap benefits in innovation, quality, and safety. For example, teams that feel safe are more likely to report near-misses and “weak signals” of trouble, allowing proactive fixes before a serious incident occurs (O’Dea & Flin, 2003). In high-risk industries, these small warnings are the canaries in the coal mine – if people are too intimidated to voice them, the organization flies blind into danger.

Case Study: Transforming an Offshore Platform Through Care

To see the difference between command and care in action, consider the real-world transformation of Shell’s Ursa oil platform in the Gulf of Mexico. In the late 1990s, Ursa was one of the world’s deepest offshore rigs – technically brilliant, but culturally troubled. The environment onboard was hyper-masculine and fear-driven; crew members routinely hid mistakes and refused to admit fatigue or uncertainty (Ely & Meyerson, 2008). One Shell manager observed that “this place won’t be safe to operate unless we change the culture.” In response, Shell executives took what was then a radical step: they brought in an outside leadership consultant, Claire Nuer, who introduced emotional intelligence and psychological safety practices to the roughnecks and roustabouts on the rig. Through a series of workshops, the platform’s leaders and workers were encouraged to share their fears, discuss near-misses openly, and express empathy for one another – behaviors that had been unheard of in that setting.

The initial pushback was strong. Many veteran crew thought these “touchy-feely” sessions were a waste of time. But as the workshops continued, a remarkable shift took place. Workers who had never spoken up began voicing concerns; the team started catching and correcting small problems collaboratively; managers learned to listen rather than just bark orders. One crew member reflected on the change: “They saw that the ones improving safety weren’t the loudest or toughest guys. It was the ones who cared about others, listened well, and stayed curious.” In other words, the traits that made the biggest difference were emotional intelligence and genuine concern – not traditional machismo.

The outcome? Over the next few years, Shell saw an 84% drop in accidents on that platform (Ely & Meyerson, 2008). This staggering improvement was achieved without any major new safety technology or punitive enforcement blitz. It happened because people felt safe enough to speak up – to stop work when something seemed off, to admit when they were too tired or distracted, and to support each other in maintaining vigilance (Hooper-Rees, 2025). The success at Ursa was so clear that Shell expanded the approach company-wide, leading to a documented 84% decline in the company’s overall accident rate (Joseph, 2020). Harvard researchers Robin Ely and Debra Meyerson studied this cultural overhaul and concluded that “extinguishing macho behavior is vital to achieving top performance” in high-risk teams (Ely & Meyerson, 2008). The men who rose to become the new safety leaders on Ursa were not the stereotypical “toughest guys” – they were the ones who demonstrated mission-focus and empathy, who actively listened and learned (Ely & Meyerson, 2008). In short, caring became the ultimate tool for control – control of risk, that is.

This case underscores a powerful lesson: psychological safety protocols can transform team dynamics even in extreme environments. An offshore platform manager who moves from a command stance to a caring stance isn’t coddling his team – he’s unleashing their capacity to manage danger proactively. By instituting practices such as regular emotional check-ins, no-blame incident reviews, and peer support programs, leaders create a platform (figuratively and literally) where speaking up saves lives. It’s important to note that caring leadership does not mean lowering standards or tolerating complacency. On Ursa, accountability actually increased after the culture change – people took ownership of safety because they felt invested and respected, not because they were afraid of punishment. This aligns with broader research showing that in high-reliability organizations, trust and accountability go hand in hand: workers are more likely to follow rules and strive for excellence when they believe leadership has their back (Reason, 1997).

Another illustrative example comes from the offshore wind industry in Europe. Ørsted, a Danish company known for its wind farms (and formerly an oil & gas company), recognized that scaling up projects like the massive Hornsea 2 wind farm required a new kind of safety leadership. Ørsted partnered with a training firm to establish a safety leadership center and immersive program called “Thrive,” which uses simulations and role-playing to instill a caring, speak-up culture among all workers (Perrigot, 2024). Over 2,000 employees went through this program, and 85% reported increased confidence in challenging unsafe behaviorsafterward (Perrigot, 2024). That is a huge boost in psychological safety. The investment paid off: Hornsea 2 was built with an exemplary safety record relative to the wider industry, and the approach is being carried forward to new projects. As Lord Cullen (who led the Piper Alpha disaster inquiry) noted, no amount of formal regulation can substitute for such effective safety leadership at all levels. The takeaway is that whether on a North Sea oil rig or a North Sea wind farm, the principles of caring leadership and empowered teams lead to concrete safety improvements.

A New Model for Safety Leadership in Wind Energy

For executives in the wind energy sector across Europe and the Middle East, the mandate is clear: it’s time to redefine safety leadership from the ground up. The rapid growth of offshore wind, from the North Sea to the Gulf of Suez, brings not only technical and logistical challenges but also a pressing workforce challenge. By 2030, hundreds of thousands of new technicians will join the global wind workforce (Global Wind Energy Council, 2021). Many will be young, diverse, and less willing to endure the hardships that older generations took for granted. They will expect their employers to prioritize safety in a holistic sense – including mental well-being and work-life balance – or they will simply vote with their feet. This generational shift is already visible. A 2023 survey in the GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) countries found that two-thirds of employees reported mental health symptoms and one-third showed burnout in their jobs, prompting Gulf governments and companies to start actively addressing workplace mental health for the first time (Kamel, 2023). In Europe, regulatory bodies are implementing directives that force companies to assess and mitigate psychosocial risks at work. These trends point to an unavoidable conclusion: safety leadership must evolve, or wind companies will face serious talent and safety problems.

So what does “From Command to Care” leadership look like in practice for wind energy project managers and HSE (Health, Safety, Environment) leaders? It starts with shedding the old paradoxical belief that caring about people dilutes operational rigor. On the contrary, caring is the new rigor. A manager on a remote wind farm in the North Sea or a desert turbine site in the Middle East can maintain discipline and be approachable. They can insist on high standards while also showing empathy. For example, rather than ordering a technician to climb in dangerous weather “because we’re on deadline,” a caring leader will openly discuss the risks, encourage the tech to voice any hesitation, and potentially delay the task if safety margins are thin. Over time, this builds a culture where everyone feels responsible for everyone else’s safety. On a practical level, project managers are finding success by implementing a few key strategies:

· Establish “stop work” authority for all – Every crew member, regardless of rank, must have the explicit right to halt an operation if they see a hazard. Critically, leadership must celebrate (not punish) those who use this authority (Conklin, 2019). This policy sends a clear signal that the company cares more about people than about short-term output.

· Practice visible empathy and engagement – Leaders should regularly visit the field, ask open-ended questions, and actively listen to worker concerns. Something as simple as a daily toolbox talk where managers share a personal safety story or admit a past mistake can humanize the leadership team and break down communication barriers. For instance, BP’s leadership began informal “safety chats” at its Middle East sites where managers talked about mental health and burnout openly, leading to a marked increase in workers utilizing counseling resources (SPE, 2024).

· Integrate psychological safety into training – Traditional safety training in high-risk industries has focused on technical procedures and compliance. Those remain important, but training must also address soft skills like communication, teamwork under pressure, and stress management. The Ørsted “Thrive” program is a prime example: it immerses participants in a realistic incident scenario and then teaches them communication tools to change the outcome by collaborating and speaking up (Perrigot, 2024). Wind companies should ensure that any safety leadership training includes modules on fostering trust, resolving conflicts constructively, and recognizing when a team member is struggling (Offshore Energies UK, 2019). A safety leadership training curriculum that treats “psychological safety protocols” as core content will produce supervisors capable of transforming team dynamics.

· Encourage reporting and learn from near-misses – A caring safety culture treats near-miss reports and safety suggestions as gold. Leading firms have implemented simple reporting apps and non-punitive review boards to analyze near-misses anonymously. One European wind operator noticed a jump in near-miss reports after explicitly assuring workers that no one would be blamed for honest mistakes – instead, the focus was on identifying system fixes. As a result, they fixed dozens of small issues (e.g., tool tethering, ladder placements) before they caused injuries. This proactive approach only thrives when workers trust that management’s priority is learning rather than blaming (Reason, 1997).

· Promote work-life balance in rotations – In extreme environments, fatigue and stress can be deadly. Caring leadership means acknowledging human limits. Some Middle East wind projects have revised their rotation schedules (e.g., 2 weeks on/2 weeks off instead of 3/1) after data showed performance and mental health dropped sharply after 21 days on-site. European offshore wind firms, similarly, are exploring more frequent crew changes and onboard amenities to reduce isolation. Leaders who champion these changes show employees that well-being is a strategic priority, which in turn breeds loyalty and engagement.

Implementing these changes is not always easy. It often requires overcoming ingrained attitudes among veteran supervisors who came up in the “command” tradition. That’s why leadership from the top is essential – executives must clearly articulate that caring is not coddling, it’s about creating conditions for peak performance. They should highlight case studies (like Shell Ursa or Ørsted Hornsea) where caring leadership led to better results than old-school methods. Over time, success stories from within the organization itself will emerge: perhaps a platform manager in the Gulf of Suez who, by introducing psychological safety and wellness checks, saw team turnover drop and safety audits improve; or a North Sea installation crew that handled an emergency flawlessly because everyone communicated openly without fear. These wins reinforce the new way and help convert the doubters.

Actionable Takeaways for Executives

For leaders ready to act on these insights, here are concrete steps to begin redefining safety leadership in your organization:

1. Lead with vulnerability: Share your own experiences with mistakes or near-misses in safety meetings. When an executive admits, “I once made a bad call that nearly caused an accident,” it shatters the myth of infallibility at the top and frees others to speak up (Edmondson, 2019). Commit to a leadership style that says “I’m not perfect, and I don’t expect you to be. What I expect is honesty and learning.”

2. Implement psychological safety training: Don’t assume managers know how to foster an open climate – train them. Workshops or coaching on active listening, conflict resolution, and supportive feedback can equip leaders with tools to build trust in their teams. Make “safety leadership training” a required component for all supervisors and tie it to performance evaluations.

3. Establish robust support systems: Create Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs), confidential counseling lines (accessible even from offshore), and peer support groups. Publicize these resources and encourage their use. When employees do use them, treat it as a positive sign of proactive behavior, not a stigma. Supporting mental health overtly will reduce the “invisible workforce” of struggling employees and improve overall safety and productivity.

4. Revise policies to reflect care: Audit your HR and safety policies through a new lens. Do overtime rules, travel schedules, or incident investigation procedures inadvertently penalize people for being human? For example, if your incident forms ask “Who is at fault?” you might replace that with “How can we prevent this in the future?” (a simple but powerful shift). Ensure that no policy discourages reporting or suggests that taking a break when exhausted is a sign of weakness.

5. Measure and reward the right things: Expand your safety KPIs beyond lagging indicators like injury counts. Include metrics for safety climate or psychological safety (e.g. via periodic anonymous surveys). Reward managers not just for low incident rates – which can sometimes drive problems underground – but for visible safety leadership behaviors. This might include recognition for teams that submit lots of near-miss reports, or bonuses for managers who improve their safety climate scores significantly. By aligning incentives with the care-driven model, you embed it into the organization’s DNA.

By taking these actions, executives and senior managers send a powerful signal that safety leadership transformation is more than a slogan – it’s a strategic imperative. It tells the workforce: we hear you, we trust you, and we are in this together. This message is especially resonant in Europe and the Middle East today, where companies are competing for skilled labor and navigating evolving regulations. A company that genuinely cares will attract the best talent (indeed, 81% of employees say they seek employers that support mental health (American Heart Association, 2022) in surveys) and will position itself ahead of regulatory curves rather than behind.

Conclusion: Embracing a “Care Culture” for Peak Performance

The era of “command and control” safety leadership is ending, not because compliance no longer matters, but because compliance alone cannot tackle the complex human factors at play in extreme work environments. The new era, the “care culture”, recognizes that true safety is achieved when people at all levels are engaged, respected, and empowered to act. It’s a culture in which a supervisor’s tough façade is less important than his willingness to listen, in which a technician’s ability to voice a concern is valued as much as his ability to turn a wrench. Far from weakening operational performance, this shift from command to care has been shown to enhance it – reducing accidents, improving morale, and boosting productivity (Ely & Meyerson, 2008; Rowell et al., 2024). As one roughneck-turned-leader eloquently put it, “We didn’t lose our edge; we gained a conscience – and that made us safer and stronger.”

For the high-risk industries of Europe and the Middle East, and specifically the burgeoning wind energy sector, embracing this new model of safety leadership is not just about avoiding disaster – it is about building a sustainable future workforce. The coming generation of leaders and workers will thrive in organizations that challenge the old paradox and prove that caring and high performance are two sides of the same coin. By cultivating psychological safety, encouraging open communication, and caring for their teams’ well-being, today’s executives can ignite a leadership awakening that propels their companies to new heights of safety and success. The transformation may be challenging, even controversial to some, but it is undeniably data-backed and necessary. The path forward is clear: it’s time to trade the hard hat for the listening ear, the command for the compassionate, and in doing so, safeguard both our people and our industry’s future.

References

Daigneault, S. (2024, December 2). Safety in the Workplace: Managing the Expectations of Millennials and Gen Z. Occupational Health & Safety Magazine ohsonline.comohsonline.com.

Ely, R. J., & Meyerson, D. (2008). Unmasking Manly Men. Harvard Business Review, 86(7), 44-53 empathy.guruempathy.guru.

Hooper-Rees, B. (2025, June 6). What an Oil Rig Taught Us About Emotional Intelligence. Hooper-Rees Blog. hooper-rees.comhooper-rees.com.

Joseph, S. (2020, February 14). Mining, extraction industries still have highest U.S. suicide rate. Reuters

Kamel, D. (2023, January 30). GCC countries start prioritising mental health in the workplace. The National News (UAE)

National Safety Council. (2023, May 25). Workers Who Feel Psychologically Safe Less Likely to be Injured at Work nsc.org.

Perrigot, S. (2024, August 20). Enabling Safety in the Offshore Wind Industry: A Legacy of Innovation and Leadership. PES Wind/LinkedIn Pulse. linkedin.coml

Rowell, D., McMillan, D., & Carroll, J. (2024). Offshore wind H&S: A review and analysis. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 189, 113928

Shell Ursa Case (as cited in Ely & Meyerson, 2008). Referenced via Ely & Meyerson and Hooper-Rees: demonstrates 84% accident reduction after culture change on an oil platform empathy.guruhooper-rees.com.

Perrigot (2024). Ørsted “Thrive” Program. Real-world example of a safety leadership training initiative in offshore wind that immerses workers in realistic scenarios to teach communication and psychological safety linkedin.comlinkedin.com. (Illustrates how investment in soft skills training yields tangible benefits in safety outcomes.)

National Safety Council, Injury Facts (2023). Data source for psychological safety vs injury rates nsc.org.