Beyond the hard hat: why traditional safety training misses the mark in high-risk environments?

Beyond the Hard Hat: Why Traditional Safety Training Misses the Mark in High-Risk Environments

In high-risk industries like offshore oil & gas, mining, and construction, safety has traditionally focused on hard rules and hard hats, meaning personal protective equipment (PPE), checklists, and technical training. Yet even as companies pour resources into these conventional safety measures, a sobering reality remains: human factors underlie the majority of industrial accidents. Research indicates that 70–80% of major accidents in high-risk sectors are attributable to human error (Zhang, Feng, & Lei, 2022). In mining, for example, organizational and human factors together account for about 80% of incident causes. Simply put, the best equipment and procedures cannot fully safeguard operations if the people running them are stressed, fatigued, or not psychologically engaged.

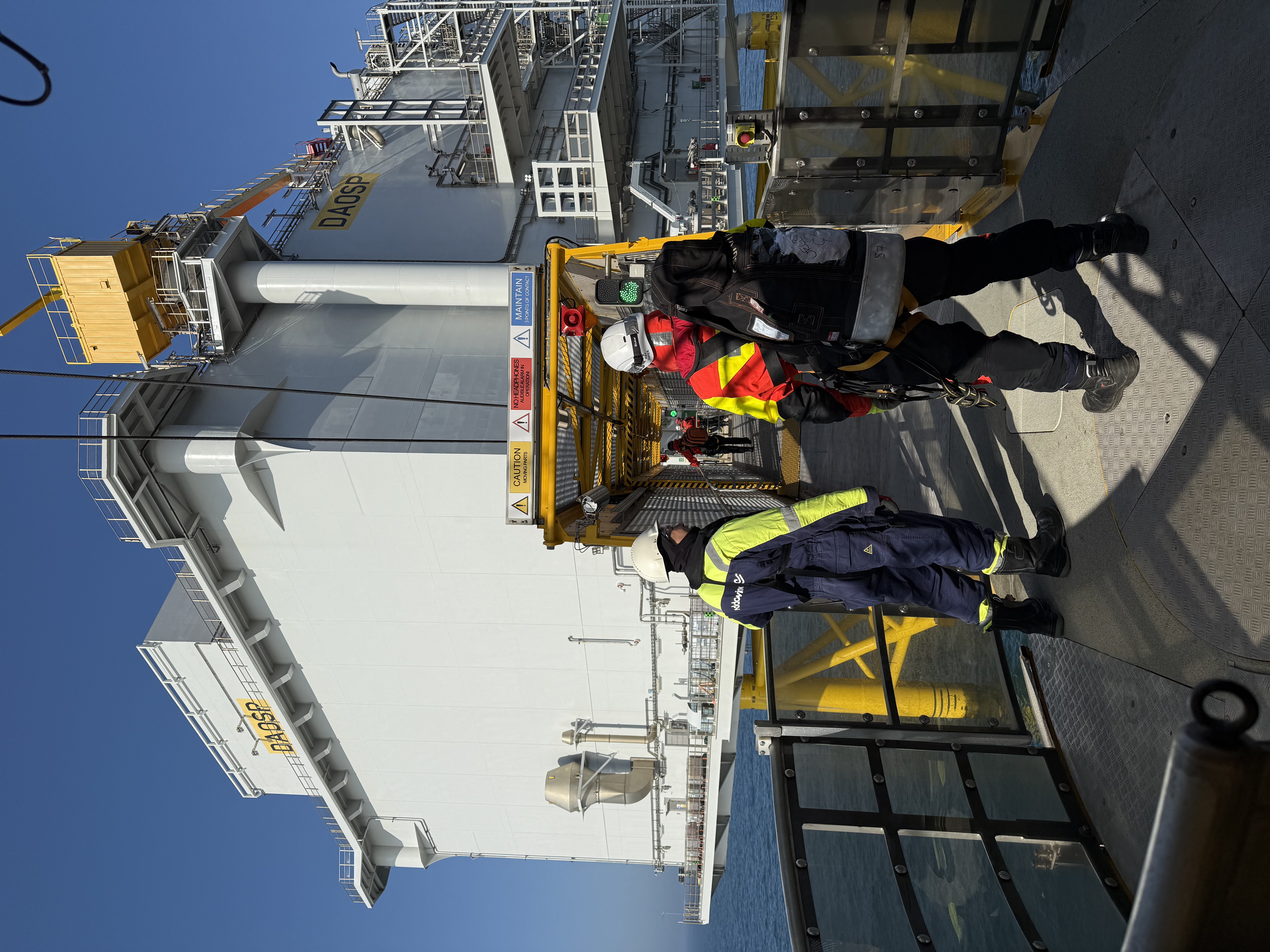

This insight exposes a critical weakness in traditional safety training. Conventional training programs, focused on rules, drills, and PPE, often fall short by neglecting the human element. They assume that if workers simply follow procedures, accidents won’t happen. However, real-world disasters frequently stem from less tangible issues: mental fatigue, communication breakdowns, stress-induced mistakes, and a flawed safety culture. In environments such as offshore platforms or remote drilling sites, workers face weeks or months of isolation and extreme conditions. If safety training doesn’t address psychological resilience and human behavior, it leaves a gaping hole in the defenses.

This article, the first in our Human Factors Revolution series, challenges industry orthodoxy with data-backed insights. We explore why traditional training alone is not enough for high-risk environments and how forward-thinking organizations in Europe and the Middle East are augmenting safety programs with human factors training and real-time psychological monitoring. The goal is not to discard “hard hat” training, but to go beyond it, building a safety culture that recognizes the human mind as a critical safety system in its own right.

The Swiss Cheese Model: Layers of Defense and Hidden Holes

To understand where traditional safety training falls short, it helps to visualize how accidents occur. James Reason’s famous Swiss Cheese Model provides a powerful framework (Reason, 1990). Imagine an accident as a trajectory trying to punch through layers of Swiss cheese, where each layer is a defense: engineering controls, procedures, training, supervision, etc. No layer is perfect. Each has holes (weaknesses). An accident happens when the holes momentarily align, allowing a hazard to pass through all defenses.

In high-risk environments, traditional safety training is one of the cheese slices. It’s supposed to fortify the human performance layer by imparting knowledge and skills. However, if that training doesn’t address key human factor “holes”, it leaves the entire system vulnerable. For instance, a worker might know every procedure (training layer solid), but if chronic fatigue or stress (a latent human factor hole) is present, their ability to follow procedures under pressure might fail. An offshore installation manager described it well: you have to be aware of all the different safety barriers and proactively fix their holes so they never line up into a disaster.

In offshore oil & gas, isolation and long rotations create unique latent holes. Unlike a typical workplace, an offshore platform or remote drilling camp might keep workers away from home for weeks or months. Fatigue, loneliness, and mental strain can silently erode the safety defenses. These are not issues a traditional hard-hat training or a yearly safety lecture can fix. They require a deeper approach, one that treats mental well-being and human behavior as integral to safety.

Active Failures vs. Latent Conditions

The Swiss Cheese Model also distinguishes between active failures (immediate unsafe acts, e.g. a misjudgment by a worker) and latent failures (hidden problems like poor design, or a fatigued state, lying dormant until they contribute to an accident). Traditional safety efforts often fixate on active failures (“Operator X didn’t follow procedure Y”). But high-risk industries have learned that latent conditions, such as a toxic safety culture or worker burnout are often the real culprits. If training programs ignore these latent human factors, they fail to plug holes that grow bigger over time.

For example, investigations into past offshore disasters (from Piper Alpha in 1988 to more recent incidents) frequently cite organizational culture and human errors as root causes. A retrospective analysis in the oil industry found that over 80% of accidents involved some form of human error or organizational lapse(Zhang et al., 2022, p. 2). This doesn’t mean workers are simply “the problem”, but rather that systems must be designed around human limitations. Traditional training that assumes humans are infallible (or that they can be “trained out” of error) misses this point. Instead, modern safety thinking emphasizes designing defenses with human factor awareness, so that one person’s slip-up doesn’t spiral into a catastrophe.

Isolation, Stress, and Safety: The Reality of Offshore Work

Consider the life of an offshore worker on a North Sea oil platform or a Middle Eastern remote desert rig. They might work 12-hour shifts for 14 days straight, then spend 14 days off rotation, or even longer stretches away from family. The work is physically demanding and mentally taxing. Social isolation and harsh conditions are not just HR issues. They directly impact safety performance. Multiple studies have documented a clear link between workers’ mental health and their likelihood of accidents (Alroomi & Mohamed, 2021; D’Antoine et al., 2023).

- Mental health and accident risk: In a study of remote oilfield employees, researchers found that occupational stressors (like long shifts and isolation) had a significant negative effect on safety behavior. Anxiety and depression symptoms among workers mediated this relationship. In other words, stress led to poorer safety compliance largely because it caused mental health declines (Alroomi & Mohamed, 2021). The authors concluded that mental health and fatigue act as risk factors for incidents, and recommended that companies help workers manage stress and fatigue to improve safety (Alroomi & Mohamed, 2021, p. 2).

- Prevalence of mental health issues: Alarming data are emerging about mental health in high-risk jobs. According to a 2024 industry survey, 40% of remote rotational workers (onshore/offshore) reported experiencing suicidal thoughts while on duty (McFarland, 2024). Similarly, an older study in the North Sea found nearly 1 in 5 offshore workers met criteria for a psychological disorder like anxiety or depression (Cooper & Sutherland, 1987, as cited in Morris & Dewett, 2021). These numbers are far above general workforce averages. They underscore that workers in hazardous, isolated environments carry an extra psychological burden that can compromise their attention, decision-making, and ultimately, safety.

- Fatigue and human error: Long shifts and fatigue go hand-in-hand. Fatigue has been shown to impair cognitive function similarly to alcohol intoxication. In the oil and gas sector, fatigue from extended work hours is recognized as a major contributor to accidents (Wyly, 2020). One analysis of oilfield accidents found that human error (often exacerbated by fatigue) was the leading cause of fatal incidents, more so than mechanical failures or environmental factors. Executives should view managing fatigue not just as a wellness initiative, but as core safety management.

These findings drive home a controversial but data-backed position: traditional safety training, no matter how thorough on paper, misses the mark if it ignores mental health and human psychology. Teaching procedures and issuing protective gear addresses the “easy” parts of safety. But the “hard” part is what goes on in a worker’s mind after 20 days offshore, when stress and fatigue accumulate. If a worker is mentally distracted or emotionally drained, the fact they scored 100% on a safety quiz last month offers little protection in a crisis moment.

Where Traditional Safety Training Falls Short

Why do conventional training programs struggle to address these human factors? There are several inherent limitations in the old approaches to safety training, especially in complex, high-risk workplaces:

- One-Size-Fits-All Content: Traditional safety training often involves generic slide decks, dense procedure manuals, and classroom lectures. These assume every trainee learns the same way. In reality, workers have diverse learning styles and backgrounds. A standardized course might be too easy for some, too fast or irrelevant for others. Individual cognitive differences (memory, attention, risk perception) are rarely accounted for. This “check-the-box” training can leave significant skill and knowledge gaps unaddressed.

- Lack of Realism and Engagement: Safety drills and tabletop exercises can never fully recreate the chaos and pressure of a real emergency. Conventional training usually fails to simulate the sensory overload and emotional stress of, say, a blowout or mine collapse. As a result, workers may freeze or make poor decisions in an actual crisis, even if they aced the training scenarios. The extreme conditions of high-risk environments (noise, heat, time pressure) are difficult to safely replicate with old training methods, meaning the first time workers experience true high-stress decision-making might be during an actual disaster, which is too late.

- Limited Monitoring and Feedback: In a typical training session, instructors can’t monitor every trainee’s performance closely, especially if exercises are spread out over a large site. People can pass a training module despite lingering misunderstandings or bad habits, because instructors simply don’t catch every mistake. Traditional methods also tend to provide feedback long after the fact (e.g. test results days later) if at all. There is little real-time correction of unsafe technique or reinforcement of good practice. This gap means unsafe behaviors can go unchecked until they cause an incident.

- Neglect of Soft Skills and Culture: Safety culture (the shared values and behaviors that determine “how we do things here”) is hard to teach via a PowerPoint. Traditional training focuses on rules (“Do X, don’t do Y”) rather than fostering critical thinking, teamwork, and a questioning attitude. It rarely acknowledges cognitive biases (like overconfidence or normalization of deviance) that lead workers to take risks. Emotional and communication skills (e.g. how to speak up about a hazard, how to cope with stress) are usually glossed over. This leaves a dangerous void: employees may know the rulebook, but not feel empowered to stop a job when something seems off, or not know how to manage the psychological pressures of the job.

- Safety = Compliance Mindset: Perhaps the biggest flaw is equating safety with mere compliance. Traditional programs often emphasize passing a test or meeting a regulatory requirement. Workers in these programs can internalize the idea that as long as they comply (check the boxes, wear the PPE, fill the forms), they are “being safe.” In reality, safety is an active, continuous process of anticipation and adaptation, not just compliance. A compliance mindset can breed complacency. People stop thinking proactively about risks because “the procedure will save us.” This is industry-challenging to admit: following rules isn’t enough. For example, the Deepwater Horizon disaster (2010) occurred on a rig that had just won a safety award for zero incidents, highlighting that a paperwork-perfect safety record can mask underlying vulnerabilities in safety culture.

In summary, conventional training treats safety as a static skill when, in fact, it is a dynamic human performance that fluctuates with conditions and mental state. It prepares workers for known hazards but not for the unexpected. It tells them what to do, but not always why, and seldom how to think in a crisis. As one safety expert bluntly put it, “traditional training builds hard hats, but not hard minds.”

Toward Human Factors Training and Safety Culture 2.0

If traditional training is missing these pieces, what does a more holistic, human-centered safety traininglook like? Leading companies in Europe and the Middle East are pioneering approaches that integrate human factors science, technology, and safety culture development. The aim is to fill the gaps. To train not just for tasks, but for mindset, resilience, and adaptability. Key elements include:

1. Embedding Human Factors Education: Human factors training goes beyond the physical tasks and teaches about the cognitive and psychological aspects of work. This can include modules on fatigue management, stress awareness, communication, and teamwork under pressure. For instance, airlines have long used Crew Resource Management (CRM) training to improve team decision-making and break down authority gradients in the cockpit. Similar principles are being applied in oil & gas and mining. Workers learn about common human errors (like confirmation bias or loss of situational awareness) and how to guard against them. They practice speaking up if they notice someone (even a supervisor) is about to make a mistake. This shifts safety from a rule-following exercise to a shared responsibility and cultural norm. As evidence of this shift, companies are even training leaders to show vulnerability about mental health, e.g., a drilling manager openly discussing his own stress so that crew members feel comfortable seeking help (McFarland, 2024, p. 3). Such cultural changes start with education and frank dialogue, not with box-ticking courses.

2. Real-Time Psychological Monitoring and Support: Perhaps the most cutting-edge innovation is the use of technology to continuously monitor and support workers’ mental well-being. Leading operators now employ real-time monitoring tools alongside traditional safety metrics. For example, some North Sea offshore companies have introduced wearable smartwatches and sensors that track workers’ vital signs and stress indicators throughout their shift. These devices can detect elevated heart rate, fatigue tremors, or irregular sleep patterns, early warning signs that a worker may be under excessive stress or fatigue. If thresholds are crossed, alerts can be sent to supervisors to intervene, or to the worker themselves to take a break. One 2018 pilot program in the UAE showed that smartwatch monitoring of oilfield workers’ stress levels led to quicker identification of fatigue and potentially prevented incidents (Journal of Petroleum Technology, 2018). Another initiative in the Gulf region by ADNOC uses real-time data from VR training simulators and wearable tech to ensure workers are mentally fit for duty each day (Health & Safety International, 2023).

It’s not just wearables. Some companies also use digital platforms for psychological check-ins. Workers might fill out a daily mood questionnaire on an app or have access to a confidential counseling hotline. The data (kept private and aggregate) helps the company gauge overall workforce mental health. By treating metrics like stress levels, burnout risk, and job satisfaction as key performance indicators (KPIs), organizations are placing mental safety on par with physical safety. This is a paradigm shift. It can be controversial. Not everyone is comfortable with the idea of being “monitored” psychologically. However, when implemented with transparency and consent, many employees appreciate that their employer cares about their emotional well-being, not just their output. Crucially, this proactive monitoring can catch problems before they manifest as accidents, much like equipment sensors detect anomalies before a breakdown.

3. Advanced Simulation and Virtual Reality (VR) Training: To overcome the realism gap in training, companies are investing in high-fidelity simulations. VR and augmented reality (AR) training programs allow workers to practice emergency responses in immersive environments that mimic the chaos of actual incidents. European energy firms have used VR firefighting simulators where trainees must virtually navigate explosions and smoke on an offshore platform, experiences too dangerous to recreate physically. The benefit of VR is twofold: it exposes workers to high-stress scenarios in a safe setting, and it also records detailed data on their performance. Did the trainee check the virtual pressure gauge? How long did they take to make a decision? This data provides pinpoint feedback. Research has shown that simulation training significantly improves response time and decision-making under stress compared to traditional drills (Martens et al., 2022). Moreover, VR is scalable; multiple crew members can train together from different locations, fostering teamwork across sites.

4. Wearables and Training Analytics: As part of an overall “digital safety” approach, wearable tech is not only used in the field but also during training exercises. In mining, for example, trainees now wear devices that monitor their heart rate and movements during mock emergency drills. If a trainee’s biometric data shows extreme stress or confusion at a certain point in the drill, instructors can identify where additional coaching is needed. One mining safety program reported that biometric feedback helped trainers intervene when a miner showed signs of panic during a simulation, preventing a negative learning experience (Nerbø, 2021). Over time, aggregating this data helps personalize training: rather than one-size-fits-all, programs can adapt to each worker’s weaknesses, whether that’s handling pressure, communication, or procedural knowledge. This use of data and AI to tailor safety training is revolutionary. It transforms training from a periodic formality into an ongoing, data-driven improvement process.

5. Emphasizing Safety Culture and Leadership: Technical fixes alone won’t revolutionize safety. Companies are pairing these innovations with efforts to strengthen safety culture at the leadership level. In practice, this means senior executives and managers are being trained to value and model key behaviors: reporting near-misses without blame, encouraging rest and work-life balance, and rewarding proactive safety actions (not just lack of accidents). European regulators are nudging this direction too. For instance, the UK’s Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and the EU OSHA have issued guidance on managing psychosocial risks in the workplace, making it clear that employers have a duty to control stress and fatigue just as they control chemical hazards. The new international standard ISO 45003:2021 provides a framework for organizations to manage psychological health and safety (International Organization for Standardization [ISO], 2021). Forward-thinking companies are voluntarily aligning with these guidelines, anticipating that future regulations will likely mandate psychological risk management. By fostering a culture where mental well-being is part of “safety talk”, they stay ahead of both risks and rules.

One real-world example comes from the North Sea: the IADC North Sea Chapter’s “Mental Health in Energy” initiative. It produced an industry-wide Mental Health Charter and practical toolkit for companies to support workers’ mental health (McFarland, 2024). This industry-led movement challenges the old stigma (“tough workers don’t talk about stress”) and replaces it with a new norm: caring for your crew’s mental state is caring for safety. Companies in the Middle East are also adopting these ideas, blending them with local cultural considerations. The bottom line is that executives are recognizing human performance as a strategic priority, not just an HR issue. Safety excellence now means having both zero accidents and a resilient, engaged workforce.

Innovation Spotlight: Real-Time Data for Real-Time Safety

To illustrate how these pieces come together, consider a “day in the life” on a modern offshore platform managed by a company at the forefront of safety innovation:

- Morning Check-In: Workers begin their shift by quickly logging into a mobile app that asks “How are you feeling today?” with simple emoticons and a few questions about fatigue. The system flags anyone who reports poor sleep or high stress. The onsite medic or supervisor will discreetly follow up with those individuals to see if they need a lighter duty or a break later on. This is a far cry from old-school safety meetings that might start with stretching exercises but ignore the psychological state of the crew.

- Smart Helmets and Wearables: As work commences, each crew member wears a smart helmet and a band that monitors vital signs. One drill operator’s heart rate spikes and he appears to be breathing rapidly, data that the system recognizes as signs of anxiety or possible overexertion. The control room receives an automatic alert. A supervisor checks in via radio: it turns out the operator was struggling with a complex procedure he wasn’t fully comfortable with. The supervisor pauses the job, reviews the task with him, and brings in a second pair of eyes. In doing so, they likely prevented an accident. This kind of real-time intervention was not possible before; now technology augments supervisory safety oversight by keeping a digital eye on human factors.

- Safety Metrics Dashboard: The platform’s safety dashboard not only tracks traditional metrics like days since last incident, but also displays “psychological safety metrics” in aggregate. For example, it shows the crew’s average fatigue level, stress index, and even a “safety mood” score derived from the daily check-ins and any on-site counseling sessions utilized. Management in the head office reviews these alongside production targets. If fatigue trends are worsening, they have directives to intervene (e.g. by shortening rotations or sending out a relief crew). This data-driven approach treats mental health indicators with the same urgency as a mechanical sensor reading—a true paradigm shift in safety management.

- After-Action Reviews and Continuous Learning: When the shift ends, workers remove their wearables and data uploads to an analytics platform. Suppose there was a near-miss in the afternoon, say, a heavy tool was dropped but narrowly missed injuring someone. In the past, such near-misses might be brushed off. Now, they are gold mines for learning. The data reveals the crew had been working long hours in heat, and cognitive performance (measured indirectly by reaction times from wearable data) was declining. In the debrief, the team discusses not just what procedural lapse happened, but how human factors like fatigue contributed. They then update training protocols to schedule mandatory breaks in such conditions, and the incident is anonymized and shared across the company as a lesson. This blameless, analytical approach reinforces a culture of continuous improvement and vigilance.

The above scenario may sound ambitious, but it is rapidly becoming reality in top-tier organizations. As one industry CEO noted, “We measure what matters. For years we measured hard hats and boots on the ground. Now we’re also measuring hearts and minds on the ground.” By integrating real-time psychological monitoring with traditional safety metrics, companies gain a more complete picture of risk in high-risk environments. It’s analogous to moving from periodic medical checkups to continuous health monitoring. Problems can be caught earlier and interventions can be personalized.

Actionable Takeaways for Executives

For executives and safety leaders looking to implement these insights immediately, here are actionable steps to take your organization beyond the hard hat:

- Incorporate Human Factors into Training: Revise your safety training curriculum to include modules on fatigue management, stress awareness, communication, and cognitive biases. Train workers whyaccidents happen from a human perspective. For example, teach the Swiss Cheese Model and discuss past incidents where human factors played a role. Encourage interactive discussions rather than rote learning.

- Action: Partner with human factors experts or use resources from organizations like the Energy Institute or IOGP to develop a human factors training segment.

- Assess and Monitor Fatigue Levels: Do not wait for accidents to address fatigue. Implement a fatigue risk management system. This could be as simple as a weekly survey or as high-tech as wearable fatigue monitors. Set clear policies that anyone can call a timeout if they feel too fatigued and support those decisions.

- Action: Start capturing fatigue and overtime data in your safety reports. Treat excessive work hours or lack of rest as a safety hazard that warrants intervention (just like you would for a faulty piece of equipment).

- Leverage Technology for Realistic Drills: Invest in simulation training tools. Even if full VR is not feasible, use scenario-based drills and role-play critical situations to inject realism. Include elements of surprise or pressure in drills (while keeping it safe) so crews practice cognitive skills, not just memorized responses.

- Action: Evaluate available VR/AR training solutions for your industry or consider sending key staff to simulator training courses (for instance, wildfire fighting simulations for emergency teams, or well-control simulators for drilling crews).

- Implement Real-Time Health Monitoring (Carefully): Pilot a program for the voluntary use of health monitoring devices or apps. Emphasize that the goal is supportive (preventing incidents and improving well-being), and ensure data privacy. Start with a small group and demonstrate quick wins, e.g., show how hydration or micro-break reminders from an app improve alertness.

- Action: Identify a wearable or app (many exist for industrial safety) and run a 3-month trial on one site. Collect feedback from workers and openly share results.

- Strengthen Your Safety Culture: Set the tone from the top that safety includes psychological safety. This means senior leaders openly talking about mental health, budgeting for wellness initiatives, and integrating these topics into safety meetings. Make “human performance” a standing agenda item.

- Action: Create a cross-functional team (safety, HR, operations) to develop a mental health and well-being strategy, if you don’t have one. Simple steps could include establishing a peer support program or training managers to recognize and respond to signs of mental distress.

- Use Data and Listen to Workers: Start treating near-misses, incident reports, and even casual worker feedback as data points for human factors. Conduct thorough root-cause analyses that consider why a person made an error (Were they rushing? Miscommunicated? Unaware of a risk?).

- Action: For every incident or near-miss, add a section in the report for “Human Factors/Contributing Conditions”. Over time, analyze these to spot trends (e.g., incidents happen mostly at the end of 12-hour shifts, or only in certain teams, valuable clues that point to deeper issues).

By implementing these steps, executives can move their organizations toward a proactive, human-centered safety paradigm. It is a shift from viewing workers as either “safe” or “unsafe” based on rule compliance to viewing them as partners in risk management whose physical and mental states fluctuate and need support. This is not just a theoretical ideal. It has direct performance benefits. Studies consistently show that companies with a positive safety culture and engaged workforce have fewer accidents, lower downtime, and better productivity (Hale et al., 2019). In other words, taking care of your people is not at odds with profit; it is increasingly a prerequisite for sustained high performance, especially in industries where the margin for error is razor-thin.

Conclusion: Beyond Compliance, Toward Excellence

“Beyond the hard hat” means expanding our definition of safety. Traditional safety training (the hard hat, the checklist, the annual lecture) will always be necessary, but it is no longer sufficient. High-risk environments demand high-reliability organizations, and that requires safety systems that account for human strengths and weaknesses. By applying frameworks like the Swiss Cheese Model, we see that human factors training and mental health support are not soft topics; they are critical layers of defense that plug holes in our safety net. Forward-looking companies in Europe, the Middle East, and around the world are already demonstrating the value of this approach. They are pioneering real-time psychological monitoring, immersive training simulations, and robust safety cultures that empower every employee, from the boardroom to the frontline, to be a safety leader.

This human-centric revolution in safety is both challenging and exciting. It challenges long-held assumptions that safety is only about rules and engineering, and it requires investments in new technology and training approaches. But it is deeply data-backed and practically proven to save lives. In an age where we can predict equipment failures with sensors and AI, it’s time to apply the same rigor to predicting and preventing human failures. That means treating workers’ well-being as an integral component of operational risk management.

In conclusion, traditional safety training misses the mark when it treats safety as merely donning a hard hat. True safety excellence goes further; it acknowledges that the most complex “equipment” on any job site is the human brain. And like any critical equipment, it needs maintenance, support, and smart design to function properly under pressure. By embracing human factors, we don’t weaken our focus on rules or discipline; we strengthen it by ensuring the humans entrusted with those rules are capable, alert, and engaged. The result is a safer, more resilient organization. In high-risk environments where the stakes are life and death, that is what it takes to truly keep people safe.

References

Alroomi, A. S., & Mohamed, S. (2021). Occupational stressors and safety behaviour among oil and gas workers in Kuwait: The mediating role of mental health and fatigue. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11700. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111700

D’Antoine, E., Jansz, J., Barifcani, A., Shaw-Mills, S., Harris, M., & Lagat, C. (2023). Psychosocial safety and health hazards and their impacts on offshore oil and gas workers. Safety, 9(3), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety9030056

International Organization for Standardization. (2021). Occupational health and safety management – Psychological health and safety at work: Guidelines for managing psychosocial risks (ISO 45003:2021). ISO. (Guideline standard for psychological risk management)

Journal of Petroleum Technology. (2018, November 26). Wearable technology can help monitor health and safety of oilfield workers. JPT HSE Now. Retrieved from https://jpt.spe.org/wearable-technology-can-help-monitor-health-and-safety-oilfield-workers

McFarland, J. (2024, August 21). To fully protect our people, mental health must be a safety essential.Drilling Contractor. Retrieved from https://drillingcontractor.org/to-fully-protect-our-people-mental-health-must-be-a-safety-essential-69870

Nerbø, G. (2021, December 3). Safety training: Don’t waste your time with ineffective methods. Identec Solutions. Retrieved from https://www.identecsolutions.com/news/safety-training-dont-waste-your-time-with-ineffective-methods

Zhang, G., Feng, W., & Lei, Y. (2022). Human factor analysis based on a complex network and its application in gas explosion accidents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159315

The Law Office of George Escobedo. (2022, April 1). Mental health disorders common in oil and gas workers. George P. Escobedo & Associates. https://www.georgeescobedo.com/blog/2022/april/mental-health-disorders-common-in-oil-and-gas-wo/