Beyond physical hazards: psychosocial risks and the new safety culture in oil & gas

In the high-risk world of oil and gas, safety has traditionally meant hard hats, steel-toed boots, and strict procedures to prevent physical accidents. Yet in recent years, a quieter crisis has come to the forefront: the psychosocial risks – factors like chronic stress, bullying, fatigue, and mental health struggles – that directly impact worker safety and performance. Current developments between 2023 and 2025 reflect a seismic shift in how the industry views these issues. Major operators, regulators, and workforce leaders are acknowledging that a “safety culture” must encompass not just protection from physical harm, but also psychological well-being on the job. This blog post explores the latest trends and challenges in psychosocial safety across onshore and offshore oil and gas operations, examining how cultural attitudes and regulatory changes are both driving and testing this new paradigm. We delve into real-world examples – from near-miss incidents rooted in burnout to industry-wide mental health initiatives – to illustrate why addressing fatigue, mental health, and workplace harassment is now mission-critical. Executives in oil and gas will find practical recommendations and tools, including data-driven insights, case studies of transformation, visualized survey data, and a ready-to-use checklist for building a more resilient, psychologically safe workforce. The goal is clear: to push beyond compliance-driven approaches and foster a safety culture where “it’s okay not to be okay” – because in today’s oilfields and offshore platforms, saving lives and optimizing performance depend as much on managing psychosocial risks as on preventing falls and fires.

Psychosocial Safety Emerges as a New Imperative (2023–2025)

Over the past two years, a wave of current events and industry responses has thrust psychosocial safety into the spotlight for oil and gas companies. In May 2023, a coalition of nearly 200 energy organizations convened by the International Association of Drilling Contractors (IADC) North Sea Chapter developed a groundbreaking Mental Health Charter aimed at improving support for workers across the sector. This charter – sparked by alarming research that 40% of onshore and offshore workers reported suicidal ideation on duty – signaled a collective recognition that mental health can no longer be treated as a taboo or “personal” issue. Instead, it requires a structured, industry-wide commitment. “Despite past efforts, the needle on mental health improvement does not seem to be moving… Tools have been created, but these have failed to address the necessary cultural change,” noted Darren Sutherland, Chair of the IADC chapter, emphasizing that a top-down cultural shift is needed rather than a box-ticking exercise.

Regulators are also stepping up. Australia has taken a bold lead by formally integrating psychosocial risk management into its offshore safety regime. Updates to the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage (OPGGS) Safety Regulations in 2024 explicitly recognize mental health and psychosocial hazards as key elements of workplace safety, with new provisions coming into force by June 2025. This means offshore operators in Australia will be required to identify and control risks like excessive work hours, bullying, and even sexual harassment just as rigorously as they manage physical hazards. Victoria’s state government has likewise slated December 2025 for new workplace psychosocial hazard rules, mandating that employers assess factors such as workload pressure and isolation and implement controls (e.g. workload adjustments, anti-harassment policies, counseling support). Europe is moving in a similar direction: several countries now require stress risk assessments as part of standard occupational safety compliance, and Gulf states (such as the UAE) have launched national well-being strategies to address work-related mental health (Kamel, 2023). Even in regions without new laws, influential agencies are sounding the alarm – for instance, a 2024 U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) report warned that work-related psychosocial hazards are on the verge of surpassing many physical hazards in contributing to injuries and ill-health. All of this amounts to a clear message: psychosocial safety is no longer optional in oil and gas, but a core expectation of modern operations.

However, these changes are not without resistance. Some companies and industry veterans have initially bristled at what they perceive as an encroachment of “soft” issues into the hardheaded world of oil and gas. There is often a cultural lag – a lingering mindset that long hours, high stress, and a stoic disregard for feelings are “just part of the job.” In a few cases, initiatives like mental health training or fatigue monitoring have been met with skepticism by managers worried about costs or productivity dips. But increasingly, the pressure to change is overcoming inertia. Insurance providers and investors are beginning to ask pointed questions about psychosocial risk management as part of ESG (environmental, social, governance) metrics. Workforce expectations are evolving too: younger employees (and a growing share of experienced ones) are calling for healthier work-life balance and support, and 86% of oil and gas workers say company culture should support mental health. In short, the momentum of 2023–2025 is toward acknowledging that protecting workers’ mental health is integral to protecting their safety. The following sections examine how this plays out in both onshore and offshore environments, what specific psychosocial risks are most pressing, and how the industry’s culture is – slowly but surely – shifting from compliance to care.

Onshore vs. Offshore: Different Worlds, Same Challenges

Oil and gas operations span from offshore platforms hundreds of miles out at sea to onshore drilling sites and refineries on solid ground. Each setting comes with distinct workforce dynamics, but both share a common exposure to psychosocial stressors. It is important to understand both the differences and overlaps in order to craft effective interventions.

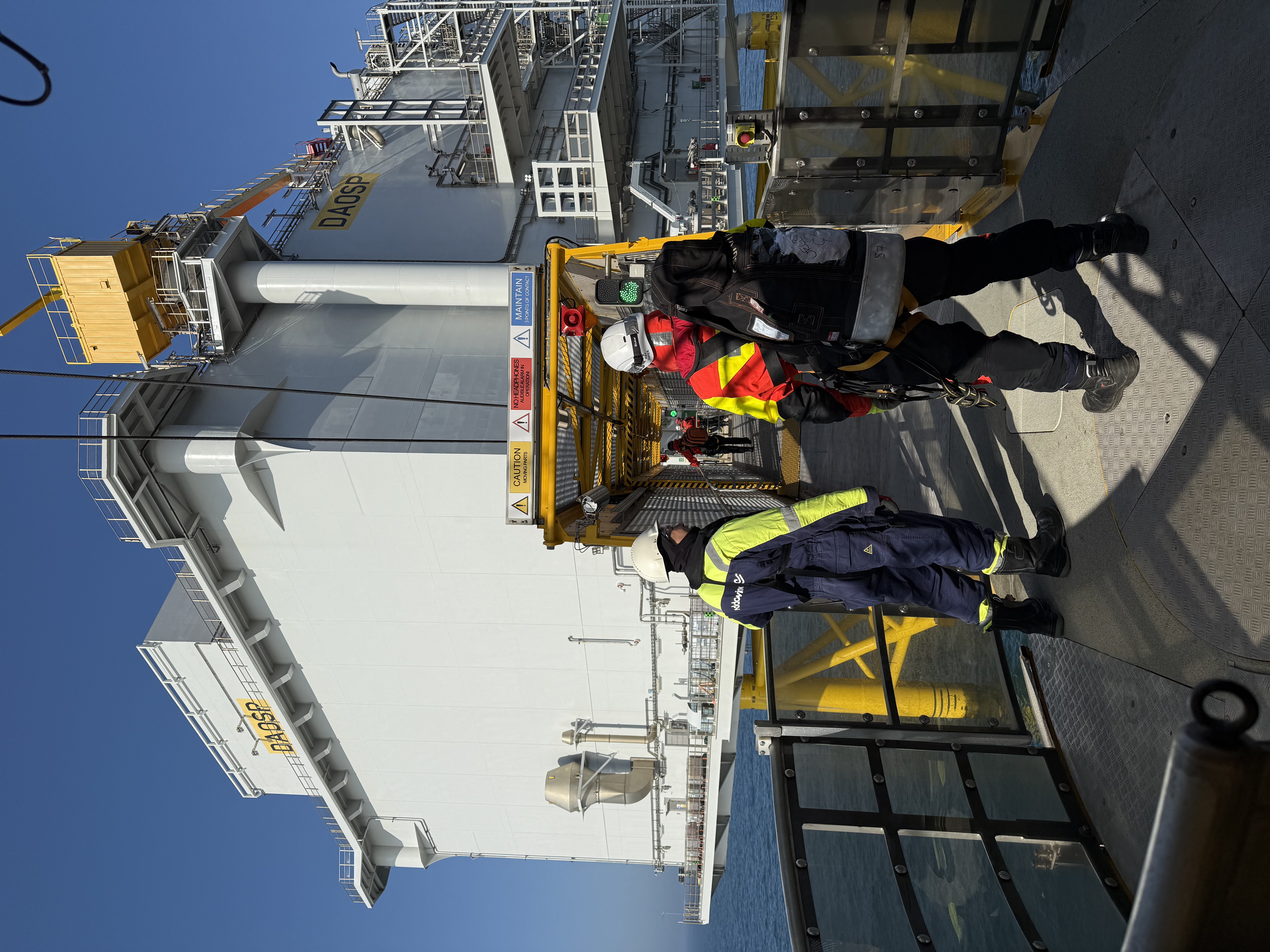

Offshore workers often face extreme remote and isolated conditions. They typically work fly-in/fly-out rotations – for example, two or three weeks on the platform, followed by an equal time off – that can strain even the most resilient individuals. While offshore, they live in confined quarters on rigs or vessels, separated from family and normal social life for long stretches. The work itself is high-hazard and high-pressure; a single mistake on an offshore oil rig can have catastrophic consequences, creating a constant undercurrent of stress and vigilance. Rotational schedules mean 12-hour shifts (or longer) day after day, leading to cumulative fatigue. Indeed, a North Sea study found that extended rotations (e.g. 21 days on/21 off) significantly eroded well-being and increased fatigue, with only 25% of offshore staff reporting satisfaction with their work-life balance. Sleep disturbances are common when working odd hours or in the noise-filled environment of a platform. Furthermore, offshore crews are typically male-dominated, and a traditional “tough guy” culture prevails; this can stigmatize admitting to stress or mental exhaustion, resulting in a code of silence where many suffer in solitude. It’s no surprise that researchers have identified “fear of speaking up” and “being seen as weak” as recurring themes in interviews with offshore workers.

Onshore oil and gas operations, while more connected to everyday life, are not necessarily a refuge from psychosocial risks. Onshore workers may return home after their shifts (in refinery or office settings), but many still work in remote oilfields (deserts, arctic tundra, etc.) or on rotational assignments in rough environments. Long commutes or extended travel to remote sites add to fatigue. On drilling sites and fracturing crews, 14- or 16-hour days during intensive operations are not uncommon. Even in corporate offices or control rooms, employees can face intense job demands and high stress during critical projects or emergencies. One major difference is that onshore workers often have readier access to external support (family, community, mental health services) on their off-hours – yet if the work culture discourages using those supports, the benefit is lost. Surveys indicate that psychosocial distress is widespread across both onshore and offshore contexts: for instance, a study across Gulf region energy companies found roughly 67% of employees – onshore and offshore – reported symptoms of poor mental health, and 33% showed signs of burnout. The sheer uncertainty in the oil and gas sector (price crashes, layoffs, boom-bust cycles) also affects everyone, onshore or offshore. As one safety executive put it, “The volatility of the industry leads to employment uncertainty and financial stress… Layoffs fuel anxiety and depression,” highlighting that job insecurity can be as corrosive on land as isolation is at sea.

Despite these contextual differences, many core issues overlap. Both onshore and offshore workers commonly endure extended work hours, high pressure to avoid costly mistakes, pervasive job insecurity, and a culture that has not historically prioritized mental well-being. Both may face hazards like workplace harassment or bullying – whether in a refinery unit or on a drilling platform – especially in hierarchical teams where pressure from supervisors can cross the line into abuse. And importantly, in both settings the outcomes of unmitigated psychosocial stress are the same: diminished attention and communication, higher error rates, accidents, and health breakdowns. In the next section, we examine these outcomes in detail, looking at how fatigue, burnout, and other psychosocial risks directly translate into safety and performance issues on the job.

The Human Cost of Fatigue, Burnout, and Bullying on Safety

Psychosocial risks in oil and gas are not abstract – they have tangible, measurable impacts on both people and operations. When workers are exhausted, burned out, or psychologically distressed, safety margins shrink dramatically. Recent studies and incident investigations have drawn direct links between these human factors and major safety outcomes in the industry.

One of the clearest ways psychosocial stress manifests is through fatigue and impaired performance. Oil and gas operations often demand long shifts and round-the-clock coverage, which can push workers beyond the limits of safe human capacity. Fatigue slows reaction times, erodes cognitive functioning, and can be as dangerous as intoxication. A vivid example came from the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB): in a 2021 Gulf of Mexico incident, an offshore supply vessel collided with a production platformbecause the mate on night watch fell asleep at the wheel. The investigation found he had worked 17 hours the previous day, far above the company’s 12-hour work limit policy (which was not enforced). The fatigued crewman literally nodded off, awakening only when it was too late to avoid the crash. Fortunately, no lives were lost, but the case caused over $360,000 in damage and could have led to a major disaster. The NTSB concluded that failure to adhere to fatigue management practices was the root cause, and it urged companies to ensure proper staffing and scheduling so no worker is put in such a perilous state again. This is just one dramatic illustration; on a day-to-day basis, chronic fatigue among oilfield crews can lead to smaller errors – a valve left unchecked, a warning signal missed, a lapse in judgment – that cascade into serious accidents.

Beyond acute fatigue, burnout – a state of physical and emotional exhaustion from prolonged stress – plagues many in the industry. Burnout is characterized by disengagement, cynicism, and reduced efficacy. For a driller or refinery operator, that might mean withdrawing from team communication and going on “autopilot”, which is deadly in a setting that requires vigilance. Industry surveys in 2023 found that one-third of oil & gas employees showed signs of burnout (e.g. extreme fatigue, cynicism about work). Burnout not only jeopardizes immediate safety (through inattention and apathy), but also drives experienced workers to quit, taking their knowledge with them. This turnover then creates staffing shortages or inexperienced replacements, which can further undermine safety performance.

Another pernicious risk is workplace bullying and harassment, which unfortunately has a foothold in some corners of oil and gas due to the high-pressure, male-dominated culture. This includes belittling or yelling by supervisors, hazing of new crew members, or ostracizing and targeting of certain individuals. Research has shown that such mistreatment correlates with higher rates of injuries and incidents, likely because it erodes team cohesion and distracts workers with fear and anxiety. In one recent qualitative study of offshore platforms, workers spoke of “micromanaging” supervisors and fear-based cultures as a significant stressor. Multiple interviewees admitted they often hesitated to speak up about safety concerns after experiencing a harsh or dismissive response in the past. This is especially alarming: when people are afraid to speak up – either about their own stress or about a potential hazard – small problems go unreported until they become big problems. Bullying also contributes to mental health issues; a survey cited in a 2023 study found that over 50% of oilfield employees had experienced workplace bullying, and notably, about 32% of those surveyed reported moderate to severe depression symptoms (a clear linkage between hostile work environment and mental harm).

Finally, the aggregate mental health burden on oil and gas workers is immense. Decades-old research first identified a “19% invisible workforce” – roughly one in five oil and gas workers suffering from diagnosable psychological disorders like anxiety, depression, or substance abuse. Unfortunately, that figure has proven resilient even in modern surveys (e.g. an October 2024 industry report again pegged about 19% of workers with such conditions). The consequences of unaddressed mental health issues range from reduced concentration and memory on the job to the ultimate tragedy of suicide. As shown in Figure 1, suicide rates in extraction work are off the charts compared to national averages. Substance abuse is another byproduct – heavy alcohol use and drug issues have been consistently reported, often as coping mechanisms for stress or isolation. These issues don’t stay “personal” for long; they directly affect safety, as impaired or distressed workers are less likely to follow safety protocols and more likely to take dangerous shortcuts. One law firm that works with oilfield injury cases noted that stressed or distracted workers are much more prone to accidents, underscoring that psychological distress often underlies what we label “human error”. The financial costs are huge as well – industry experts estimate that unaddressed mental health and stress lead to about $200 billion per year in lost productivity and turnover in the global oil and gas sector. Put simply, when a crew is bogged down by anxiety, fatigue, or interpersonal conflicts, they operate slower and make more mistakes; conversely, “a mentally healthy crew is more alert, communicative, and productive,” as one analysis noted.

Pushing for Cultural Change: From “Tough It Out” to “Speak Up”

If there is one thing that can make or break efforts to improve psychosocial safety, it is workforce culture. Oil and gas has long prided itself on a can-do, tough-as-nails culture – typified by endurance, self-reliance, and sometimes a bit of machismo. While resilience is certainly a virtue in extreme environments, the stigma against showing vulnerability has been deeply ingrained. “Mental health was never talked about on the rig – you’d get told to toughen up or laughed at,” recalls one veteran (anonymized) of a North Sea platform, describing the prevalent attitude he experienced in the 2000s. This culture of silence meant that issues like depression, chronic fatigue, or bullying went unmentioned and thus unaddressed. The result was often a vicious cycle: workers feared being seen as “weak” or losing their jobs, so they hid problems or errors, which sometimes led to accidents or health crises, further reinforcing management’s belief that individuals just needed to “handle it or leave.”

Today, there are signs of this culture slowly evolving – yet also instances where old attitudes die hard. On the positive side, leadership at many companies is beginning to model more open communicationabout mental health. In 2025, for example, the CEO of a mid-sized offshore services firm spoke at a town hall about his own burnout episode and recovery, sending a powerful signal that seeking help is acceptable. Many larger firms have started incorporating the concept of “psychological safety” into their training programs – teaching supervisors how to foster an environment where team members feel safe to admit mistakes or voice concerns without fear of ridicule or retribution. Research supports that these efforts are worthwhile: teams with a high psychosocial safety climate (i.e. management that truly prioritizes worker mental health) see stronger coworker support and higher reporting of issues before they escalate. In simpler terms, when leaders genuinely care and employees trust that it’s okay to speak up, people look out for each other and catch problems early.

Industry initiatives like the North Sea Mental Health Charter are explicitly trying to drive this cultural change. The charter’s architects noted that previous tools (like employee assistance programs or helplines) often failed because they were passive and did not tackle the root cultural barriers – workers either didn’t trust these resources or felt using them would label them as weak. The new charter emphasizes visible commitment from top leaders, peer support networks, and routine practices to normalize mental wellness discussions. Early anecdotal evidence is promising: companies that have signed on report upticks in employees approaching managers about workload concerns or personal issues before those turn into safety incidents. In one anonymized case from 2024, an offshore drilling contractor that embraced these principles saw a notable change: crews began voluntarily rotating tasks when someone was getting too tired, whereas before, workers would silently push themselves past safe limits. Empowerment to speak up – whether it’s about needing a rest, or calling out a safety hazard, or even saying “I’m not okay today” – is the cornerstone of a true safety culture. As a 2019 industry commentary put it, oil and gas needs an “open culture where employees can address mental health issues without fear of negative consequences”.

That said, not all organizations have embraced this shift. In some places, we still hear troubling reports – for example, a 2023 internal survey at a certain oilfield services company (kept anonymous) found that over half of employees didn’t feel comfortable reporting feeling overwhelmed, and a significant number believed management wouldn’t take stress-related complaints seriously. In such environments, efforts to introduce mental health programs often falter. One senior manager candidly admitted, “We had a wellness webinar, but hardly anyone attended and those who did never spoke up. I realize now they didn’t trust it was truly confidential.” Building trust is essential. Companies that pay lip service to mental well-being without addressing punitive or dismissive behaviors by middle management may see even greater cynicism from workers. In effect, cultural resistance can nullify well-intended programs.

The path forward is clearly to continue chipping away at stigma and fear. Frontline supervisors hold a lot of power here: a supportive, approachable supervisor can create a micro-culture of safety even within a larger organization. Peer champions are another approach – some rigs now have trained volunteers who workers can go to in confidence about personal struggles, providing an alternative to “telling the boss.” And everyday habits can reinforce culture: something as simple as starting each shift or safety meeting with a quick “mental health moment” – where team members can share if they’re under unusual stress or offer a quick well-being tip – can signal that mental health is part of normal work conversation. Over time, these small practices accumulate into a new norm: one where asking for a break is seen as responsible, not weak; where raising a concern is welcomed as prevention, not whining.

Changing an entrenched culture is difficult and takes time, especially in a global industry with many sub-cultures. But the combined forces of new leadership perspectives, incoming generations of workers, and external pressure mean that the “tough it out” mantra is gradually giving way to a more balanced view: toughness is still valued, but it’s recognized that even the toughest workers sometimes need support. As one charter supporter put it, “The current generation of oil and gas workers will be remembered for being at the head of the energy transition – but that transition must include improving how we care for each other. And it must start today.”

New Regulations: Carrot and Stick for Psychosocial Safety

Regulatory developments from 2023 onward reveal a mix of incentives and enforcement that aim to accelerate industry action on psychosocial risks. While we touched on some big-picture moves in Australia and elsewhere, it’s worth diving a bit deeper into what these changes entail and how companies are responding.

Australia’s approach has been particularly comprehensive. The 2024 amendments to national offshore safety legislation not only list “workforce health and wellbeing” and “psychosocial health” as areas to be managed, but they also introduce practical requirements like new incident reporting categories. For instance, offshore operators must now report and investigate safety incidents that have psychosocial factors, and there’s even a specific mechanism to report workplace harassment incidents to the regulator (a new harassment reporting form). This essentially forces companies to treat a bullying event or a mental breakdown on a rig with the same seriousness as a machinery accident. Additionally, the role of worker safety representatives (HSRs) is being strengthened, giving them more clout to address health and wellbeing issues in safety committees. The message is clear: ignoring psychosocial obligations could now lead to regulatory non-compliance, with all its consequences (investigations, penalties, or even shutdown of operations in extreme cases).

In Europe, while there isn’t yet an EU-wide psychosocial risk directive, many countries have implemented regulations or codes of practice. For example, France and Sweden mandate employers to evaluate stress and workload in their risk assessments, and Spain updated its labor laws to explicitly include psychological health. These serve as a “carrot and stick” in one: companies that proactively address these aspects not only avoid citations but also often become eligible for certain insurance benefits or certifications as safe employers. A number of international standards complement this – the ISO 45003:2021 guidelines on psychological health and safety at work have been influential, providing a framework companies can adopt voluntarily. Forward-thinking oil and gas firms have started aligning with ISO 45003 to get ahead of future mandates. As noted in the Health4Wind industry analysis, those that do so also burnish their reputation as “employers of choice” in a competitive talent market.

One notable initiative in the UK has been an Energy Institute-backed Mental Health Charter (the same North Sea charter discussed earlier) which, while voluntary, has seen rapid uptake. By late 2023, dozens of North Sea operators, drilling contractors, and service companies had signed on, committing to principles like leadership engagement, transparency in mental health reporting, and cross-company collaboration on best practices. There is a sense that such industry self-regulation can stave off heavier-handed government regulation by proving that companies can police themselves. Whether that holds true remains to be seen, but certainly regulators are watching these voluntary efforts closely.

It’s worth noting that North America has lagged somewhat on formal psychosocial regulations. OSHA (in the U.S.) still relies on the General Duty Clause to address extreme cases (e.g. if a workplace is so stressful it’s foreseeably harmful, which is a high bar). Canada’s provinces have more movement, with some adopting standards for psychological health and safety. However, even without strict rules, U.S. companies are not off the hook – lawsuits related to workplace mental harm or harassment have been rising, and workers’ compensation claims for mental stress (post-incident trauma, etc.) are becoming more recognized. Furthermore, major oil companies operating globally tend to adopt the highest standard across their operations, meaning if their North Sea division must follow a mental health protocol, it often gets implemented company-wide.

How are companies reacting overall? Many large multinationals have welcomed the clarity that new regulations bring. One HSE director quipped, “Frankly it’s easier to get budget for fatigue mitigation tech or extra crew if I can say it’s the law.” Regulations can empower safety professionals internally. On the other hand, smaller contractors worry about the cost and complexity of compliance. For example, a drilling subcontractor in Asia might question, “Do I now need a psychologist on staff to satisfy clients’ audits?” In practice, compliance doesn’t require something that specific, but it does demand formal processes: documented risk assessments for psychosocial hazards, training programs, reporting systems, etc. Companies that already have robust safety management systems are finding they can integrate psychosocial elements without too much trouble – it’s often about expanding existing frameworks (like adding a fatigue management plan, or including mental health in site orientations).

One area of possible resistance is around measuring success. Physical safety has clear metrics (injury rates, days without incident); measuring mental well-being is trickier and sometimes uncomfortable. Some executives privately express concern that if they survey their workers’ mental health, they might expose problems they’re not sure how to fix, or create liability if they don’t fix them. Regulators have tried to allay this by focusing on improvement processes over outcomes – it’s understood that you can’t eliminate all stress, but you must show you’re taking reasonable steps to mitigate it. Over time, as more companies share positive stories of how addressing psychosocial issues led to fewer accidents (and often higher productivity), the hope is that even the stragglers will see the business case and moral imperative for change.

In summary, the 2023–2025 period is marking a turning point where regulatory expectations are catching up to scientific knowledge about psychosocial risks. Oil and gas firms are being nudged – and in some cases shoved – to expand their definition of “safe workplace” to fully include mental and social well-being. Those that proactively embrace this, working with regulators and adopting best practices early, are likely to thrive (with a more stable workforce and fewer incidents). Those that resist may find themselves facing not just legal troubles but also operational ones as the human toll of inaction mounts.

Case Studies: Transformation and Cautionary Tales

To illustrate how psychosocial safety efforts can play out in practice, let’s look at two anonymized case studies – one highlighting a successful transformation and one serving as a warning about the cost of inaction. These cases synthesize real scenarios reported in industry forums and safety networks (with identifying details changed) and show the difference leadership and culture can make.

Case Study 1 – “Alpha Energy’s Turnaround”: Alpha Energy (a pseudonym for a mid-sized onshore drilling company) in 2023 faced a troubling trend: it experienced a higher-than-average rate of equipment incidents and unplanned downtime on its rigs, which investigators linked to human errors. Digging deeper, management found that many crews were running on fumes. Due to staff shortages and aggressive project timelines, drillers and technicians were logging 70-80 hour weeks routinely, and reports of burnout were surfacing in exit interviews. After a near-miss where an exhausted rig worker narrowly avoided a fatal injury, Alpha’s leadership finally decided to act. In early 2024 they launched a comprehensive Fatigue Management and Mental Wellness Initiative. This included hiring additional floater staff to reduce individual workloads, enforcing a policy that no one could work more than 12 hours in a 24-hour period (with monitoring via digital time logs), and rotating workers out after two weeks on high-intensity sites. They also brought in a psychologist to train all supervisors in recognizing signs of stress and created a peer support program – at each site, two volunteers were trained as “mental health first aiders” whom colleagues could approach confidentially. The changes paid off. Over the next year, Alpha Energy reported a 25% reduction in recordable incidents and an even greater drop (40%) in minor incidents and near-misses. Productivity improved as well – fewer mistakes and downtime meant projects stayed on schedule more often. In an internal survey, 90% of employees said they felt management genuinely cared about their well-being, up from 50% the year before. One driller wrote in a comment, “I was skeptical at first, but things have changed. We’re still working hard, but at least now if I’m dead tired I can say so, and we’ll adjust. It makes a difference – I’m more alert and we haven’t had an injury on my crew in months.” Alpha’s case demonstrates that practical steps like better scheduling, training, and support resources can translate to measurable safety outcomes. It also shows the importance of listening to warning signs – the company might not have acted if not for the brave voices in exit interviews and the wake-up call of the near-miss.

Case Study 2 – “Beta Offshore’s Culture of Denial”: In contrast, consider Beta Offshore (a pseudonym for a regional offshore contractor), which by 2025 had developed a reputation as a tough place to work – and not in a good way. Beta’s leadership was old-school and proudly so; the COO was known for saying “we’re not running a daycare” in response to suggestions about mental health days or fatigue breaks. On Beta’s platforms, overtime was the norm and anyone who complained about exhaustion was told they “aren’t cut out for offshore work.” A clique of managers at one installation also tolerated (and sometimes participated in) bullying behavior – routinely shouting at crews, singling out individuals to berate publicly for minor errors, and dismissing concerns about long shifts. Over time, this fostered a climate of fear and resentment. Workers stopped raising safety issues, figuring it was pointless or would invite retaliation. The effect on safety metrics was insidious: while Beta touted a low official injury rate (some say because workers even avoided reporting injuries), they suffered two significant process safety incidents in 2024. In one, maintenance on a critical pump was delayed because the technician, overwhelmed and afraid to admit he was behind, did not inform his supervisor; the pump failed and caused a fire (luckily contained with only equipment damage). In another, a crew member’s severe fatigue led him to improperly secure a high-pressure line, which later ruptured; he later confided he was on his 19th straight hour of work but hadn’t told anyone for fear of looking weak. Beta Offshore’s losses – both human and financial – mounted. By mid-2025, they had a turnover rate double the industry average, and experienced workers shunned their job offers. Eventually, a major client intervened: a global oil company that contracted Beta audited their operations and flagged their toxic culture and non-compliance with new psychosocial safety guidelines. Facing loss of business, Beta Offshore’s executive team was forced to confront the issue. As of this writing, they are (belatedly) bringing in an external consultancy to overhaul their approach, but the damage to their reputation and the direct costs of accidents, retraining new hires, and inefficiency have been enormous. The Beta case starkly illustrates that resisting change in psychosocial safety is a costly gamble – one that endangers lives and erodes business performance. It serves as a cautionary tale that cultural safety shifts are not just a “nice-to-have,” but an essential part of operating in the modern industry.

Conclusion

The oil and gas industry stands at a critical juncture in 2025. The traditional pillars of safety – engineering controls, procedures, and personal protective equipment – remain necessary but no longer sufficient. To truly protect workers and optimize operations, organizations must embrace the psychosocial dimensions of safety. This means recognizing that an exhausted technician, a bullied crew member, or a chronically anxious engineer can pose as much risk to a project as any faulty valve or slippery walkway. The recent cultural shifts and regulatory developments we’ve discussed reflect growing consensus on this point. Forward-looking companies are already reaping the benefits of a more holistic approach to safety, where mental well-being and physical safety are two sides of the same coin. Those companies that lag behind, ignoring the warning signs of psychosocial stress, do so at their peril – facing potential accidents, talent loss, regulatory penalties, and reputational damage.

Change is rarely easy in a tough, tradition-bound field like oil and gas. But this is a resilient industry, one that has innovated its way through countless technical and economic challenges. The challenge of fostering psychological safety and a caring work culture is no different. It requires innovation in management practices, commitment from the top, and engagement at every level. The payoff is not only compliance with emerging laws or better safety metrics, but something far more valuable: a workforce that feels truly supported and empowered to perform at its best. In high-risk sectors, where the margin for error is slim, that could be the difference between continuing the status quo or achieving new standards of excellence and sustainability.

As we move forward, let’s remember that every statistic about fatigue or mental health is ultimately about people – individuals with families, aspirations, and human limits. Taking care of them is not just a moral obligation but a strategic one. The oil and gas industry’s future will be shaped by how well it adapts to the human factor. By prioritizing psychosocial safety now, we can honor the workforce that drives this industry and ensure that every person returns home safe – and sound in mind – at the end of the day

References

Cooper, C. L., & Sutherland, V. J. (1987). Job stress, mental health, and accidents among offshore workers in the oil and gas extraction industries. Journal of Occupational Medicine, 29(2), 119–125. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3826484/

D’Antoine, E., Jansz, J., Barifcani, A., Shaw-Mills, S., Harris, M., & Lagat, C. (2023). Psychosocial safety and health hazards and their impacts on offshore oil and gas workers. Safety, 9(3), Article 56. https://www.mdpi.com/2313-576X/9/3/56#:~:text=Several%20participants%20had%20worked%20under,P29

Exarheas, A. (2023, May 19). Leading organizations create North Sea mental health charter. Rigzone.https://www.rigzone.com/news/leading_organizations_create_north_sea_mental_health_charter-19-may-2023-173241-article/

Joseph, S. (2020, February 14). Mining, extraction industries still have highest U.S. suicide rate. Reuters.https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-health-suicide-jobs-idUSKBN2082XU

Kamel, D. (2023, January 30). GCC countries start prioritising mental health in the workplace. The National News. https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/health/2023/01/30/gcc-countries-start-prioritising-mental-health-in-the-workplace/

Learning Dimensions Network. (2023, October 10). Victoria sets date for psychosocial hazards regulations: What employers need to know. LDN Blog. https://ldn.global/victoria-sets-date-for-psychosocial-hazards-regulations-what-employers-need-to-know/

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2024, April 10). An urgent call to address work-related psychosocial hazards and improve worker well-being. NIOSH Science Blog. https://blogs.cdc.gov/niosh-science-blog/2024/04/10/psychosocial-hazards/

National Transportation Safety Board. (2023, January 26). NTSB finds fatigue led to striking of an oil and gas production platform. NTSB News Release. https://www.ntsb.gov/news/press-releases/Pages/NR20230126.aspx

Safety & Health Practitioner. (2023, June 1). New mental health charter to benefit energy industry workers after almost half admitted to suicidal thoughts. SHP Online. https://www.shponline.co.uk/mental-health/new-mental-health-charter-to-benefit-energy-industry-workers-after-almost-half-admitted-to-suicidal-thoughts/

Society of Petroleum Engineers. (2024, October 22). Mental health issues in oil industry cost $200 billion annually. Journal of Petroleum Technology. https://jpt.spe.org/mental-health-issues-in-oil-industry-cost-200-billion-annually

The Law Office of George P. Escobedo. (2022, April 1). Mental health disorders common in oil and gas workers. Escobedo Law Blog. https://www.escobedolawfirm.com/blog/2022/04/mental-health-disorders-common-in-oil-and-gas-workers/