The micromanagement trap: how control culture creates chaos offshore?

Part 2 of the Leadership Awakening Series

In high-risk offshore industries like oil, gas, and wind energy, leaders often default to micromanagement as a safety strategy. The logic seems sound: tightly control operations to prevent accidents. But mounting evidence suggests this “control culture” does more harm than good. When supervisors micromanage every task and tolerate bullying or harassment, they create a psychologically hazardous environment for workers. Instead of improving safety, this culture of control breeds stress, silence, and chaos – ultimately compromising safety performance. Executives across Europe and the Middle East are grappling with this paradox: how do we maintain authority and oversight without stifling the very frontline initiative and openness that keep operations safe? This post examines why micromanagement, gender harassment, and bullying are dangerous pitfalls for offshore organizations, and how a new approach – Trusted Autonomy – can transform safety leadership in these sectors.

Controversial but Data-Backed Position: In safety-critical offshore environments, more control can mean less safety. This claim challenges traditional industry thinking, but it’s supported by emerging research. Studies show that micromanagement and abusive leadership erode workers’ mental well-being and willingness to speak up, leading to hidden problems and heightened accident risk. By contrast, organizations that foster trust, autonomy, and psychological safety see better performance and fewer incidents (Zacharatos et al., 2005). Below, we’ll explore the evidence behind these assertions and outline actionable strategies for leaders to break out of the micromanagement trap.

How Micromanagement, Bullying & Harassment Undermine Safety

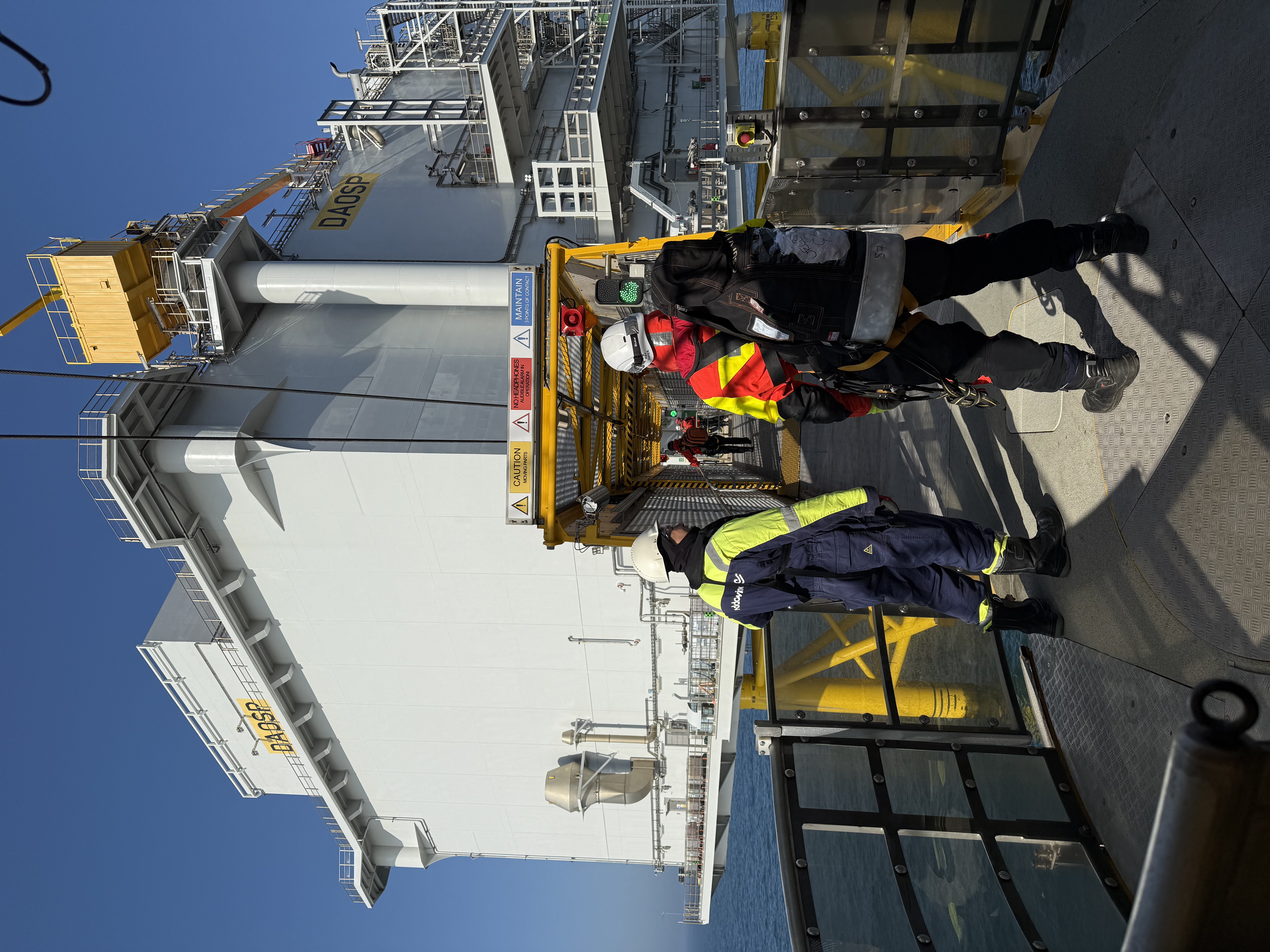

Offshore worksites (whether a North Sea oil platform or a wind farm in the Persian Gulf) are inherently risky. Adding a toxic organizational culture on top of physical hazards can create a perfect storm. Recent research has begun to identify micromanagement, bullying, and gender-based harassment as serious psychosocial safety hazards in these settings (D’Antoine et al., 2023). These behaviors aren’t just “bad management” – they actively endanger workers’ mental health and impede safety performance.

- Micromanagement and Low Trust: In a qualitative study of offshore workers, participants expressed deep frustration with managers who micromanage every detail, signaling a lack of trust in employees. Micromanagement was associated with low morale, reduced productivity, and high turnover in the workforce. By second-guessing and over-directing workers, micromanaging supervisors create a climate of anxiety and distraction. One offshore technician described it as “getting out of control… it just makes it stressful. We just wanna do our jobs… and do them safely”, lamenting that excessive control over even minor things (like how meals were prepared) made the crew’s job needlessly harder and more stressful. Research literature backs this up: micromanagement is a “costly management style” that undermines creativity and engagement (Collins & Collins, 2002). Employees under constant scrutiny tend to disengage, communicate less, and sometimes even take dangerous shortcuts to get micromanagers off their backs (Canner & Bernstein, 2014, as cited in DeLeon & Tripodi, 2022). In sum, a culture of over-control breeds resentment and complacency, not the alertness and proactivity that safety demands.

- Bullying from the Top: Offshore work cultures have long been known as tough and hierarchical, but when that toughness crosses into bullying, it creates a climate of fear. Notably, bullying in these environments often originates from higher up the chain of command. In one North Sea example, a whistleblower revealed that after a major disaster, some rig managers still bullied workers and even covered up injuries to protect safety statistics – making a “mockery” of the safety systems put in place (Macalister, 2013). Academic research confirms this pattern. A Norwegian study found workplace bullying strongly linked to leadership style, with laissez-faire or authoritarian leaders allowing bullying to fester (Nielsen, 2013). In Australia’s resource sector, over 50% of workers reported experiencing bullying, most often at the hands of supervisors or managers. This has dire consequences: being bullied was associated with a fourfold increase in psychological distress among workers and significantly higher odds of depression (Miller et al., 2020). It’s not just a morale issue – it’s a safety issue. Stressed, demoralized workers are more prone to mistakes and less inclined to actively engage in safety measures. Moreover, bullying creates an atmosphere where people “watch their back” instead of watching for hazards. If someone is fearful that speaking up or even performing too well might make them a target, they will shut down – exactly when we need them to be vigilant and communicative.

- Gender Harassment in a Male-Dominated Arena: Women working offshore often face an additional layer of psychological hazard: gender-based harassment. A 2021 study of female oil and gas professionals in Canada bluntly concluded that “gender-based harassment is common” in the industry, forcing many women to adopt a “tough skin” just to endure daily work (Murphy et al., 2021). Harassment ranges from belittling “jokes” to outright sexual harassment, creating an environment of constant stress for those targeted. Offshore crews in Europe and the Middle East remain overwhelmingly male, and this imbalance can foster a locker-room culture that normalizes offensive behavior. In the Australian offshore study, even with few women participating, two of four female interviewees reported being negatively impacted by the male-dominated environment, including bullying after reporting an incident and unwanted advances. Such experiences aren’t just individually harmful – they erode team cohesion and trust. If female engineers or technicians are marginalized or afraid to speak up due to harassment, the team loses valuable input and a diversity of perspectives on safety. In worst cases, talented women leave the industry altogether, as career progression becomes blocked by discrimination and “old boys’ club” networks (Murphy et al., 2021). This loss of skilled staff is a safety concern too, as it can lead to labor shortages or less experienced replacements in critical roles.

Chaos by Control: How a Fear Culture Compromises Safety Performance

Why do these psychological hazards directly translate into safety problems? The answer lies in how human factors influence accidents. A data analysis of incidents in high-risk sectors found that 60–80% of accidents are ultimately rooted in human factors like decision-making, communication, and stress (Rowell et al., 2024). In offshore wind, for example, 66% of crane and lifting accidents and up to 90% of vessel collision incidents cite human error as a primary cause (Rowell et al., 2024). When we examine whatunderlies those human errors, a troubling pattern emerges: environments of fear, fatigue, and mistrustset people up to fail. In other words, a punitive, high-pressure culture creates the very chaos it aims to control.

Consider the impact of fear on reporting and learning. In a healthy safety culture, front-line workers readily report near-misses, point out hazards, and stop work when something seems unsafe. This candid reporting is crucial to catch small problems before they turn catastrophic. However, in a “blame culture” fueled by micromanagement or bullying, workers become fearful of speaking up. They worry that admitting a mistake or voicing a concern will lead to retaliation, harassment, or career damage. Indeed, studies have documented that in punitive environments employees are unlikely to report near-misses for fear of harassment or retaliation (Collia & Moreau, 2020; Dekker, 2016, as cited in SafeOCS, 2020). Under-reporting is rampant when people feel unsafe: for instance, research in healthcare and aviation shows that the vast majority of near-miss events go unreported if workers expect punishment or ridicule (Hazell & Shakir, 2006). The offshore industry is no different. The Australian inquiry by D’Antoine and colleagues found that raising safety issues was often “unwelcome” in organizations with fear-based cultures, and workers had seen colleagues who spoke out get bullied or “blacklisted” by their bosses. This led to a widespread reluctance to report problems or even suggest improvements, as one respondent noted that challenging unsafe management decisions would just make you a target for more intimidation. The result is silent chaos: hazards fester unaddressed, near-misses multiply, and management remains blissfully unaware until a serious incident forces attention. As one safety expert famously put it, organizations that don’t learn from near-misses are basically “managing by luck” – an unsustainable and dangerous situation.

Another pathway from toxic culture to accidents is through mental distraction and fatigue. A workforce under chronic stress – whether from overbearing supervisors or harassment – will experience degraded cognitive performance. They are less engaged, more anxious, and often exhausted from the emotional toll. Stressed or distracted workers are more prone to accidents, as multiple studies confirm. For example, chronic workplace bullying has been linked to sleep disturbances, anxiety, and burnout (Sansone & Sansone, 2015). Offshore jobs already involve long shifts and extreme conditions; add psychological strain and the risk of errors skyrockets. In one case cited by a North Sea operator, an exhausted technician – stretched to 80-hour weeks and also dealing with constant pressure – overlooked a critical alarm and nearly caused a well control blowout. Investigators later noted the technician had been under immense stress and fatigue, worsened by a culture that discouraged refusing extra work. This is how micromanagement and production pressure can create “chaos”: workers, fearing to say no or to take a rest, push past safe limits, and small mistakes turn into potentially catastrophic events.

Lack of trust within teams also degrades safety defenses. Off the coast of Qatar or Norway alike, offshore crews rely on tight teamwork and honest communication to manage hazards. But research finds that a lack of trust between workers and supervisors correlates with poor communication about safety issues, reducing the likelihood that latent problems will be caught in time. If a technician thinks their boss will blame or belittle them, they may hesitate to ask for clarification on a confusing procedure – and then perform it incorrectly. Or a crew member might notice a potential hazard but decide not to bring it up in the safety meeting because “management doesn’t really want to hear it.” Such breakdowns in communication have been factors in real disasters. The Deepwater Horizon tragedy in 2010, for instance, had elements of a poor safety culture – workers were afraid to halt operations despite anomalies, and warnings were not heeded, contributing to the blowout (BP Deepwater Horizon Accident Investigation Report, 2010). Similarly, UK regulators noted that on some North Sea rigs, a dysfunctional culture (including bullying by supervisors) led to underreported incidents and safety reps being ignored, which “masked” serious risks until it was nearly too late (Macalister, 2013). When people don’t trust they’ll be supported, they default to silence or compliance, even if they sense danger. Over time, this erodes the organization’s true situational awareness and creates the conditions for chaos: everyone’s following orders blindly, but no one is openly sharing the bad news that leadership needs to hear.

Lastly, a hostile or non-inclusive culture can cause talent flight and skill gaps, indirectly affecting safety. Offshore projects in Europe and the Middle East have been expanding rapidly (e.g. new wind farm installations in the North Sea, drilling in the Mediterranean), and they need experienced, engaged personnel. But if high-performing workers leave due to burnout or abuse, companies end up shorthanded or staffed with greener crews. A Gulf region survey in 2023 found two-thirds of oil & gas employees reporting mental health symptoms, and one-third showing signs of burnout (Kamel, 2023). Such burnout inevitably leads to higher turnover. Every experienced driller or turbine technician lost is a wealth of safety knowledge gone – and the replacement may require years of training to reach the same proficiency. This “brain drain” can contribute to rising incident rates. In the offshore wind sector, incident data show a concentration of accidents during construction phases, when many new contractors and employees are on site (Energy Institute, 2024). Observers have partly blamed the surge of 94% more incidents in 2023 on the industry’s rapid growth outpacing the cultivation of a strong safety culture (Splash247, 2024). A revolving door of staff makes it harder to maintain consistent safety practices. Therefore, any leadership behavior (like bullying) that increases turnover is indirectly increasing safety risk. Keeping a stable, motivated team is itself a safety investment – and toxic leadership is antithetical to that goal.

Key Takeaway: A culture of fear and control creates chaos by subverting the human elements of safety. It silences the very feedback loops that prevent accidents, while amplifying stress and distraction. When workers are mentally checked out or afraid, safety systems on paper don’t translate to safety on the ground. As D’Antoine et al. (2023) concluded, multiple psychosocial stressors in the offshore environment – fear of speaking up, job insecurity, micromanagement, harassment – intertwine and “may lead to devastating consequences” if left unmitigated. The imperative is clear: to improve safety performance, companies must treat these cultural hazards as seriously as physical hazards. This means transforming leadership approaches at the very core.

From Control to Trusted Autonomy: A New Leadership Model for High-Risk Environments

How can offshore organizations escape the micromanagement trap and foster a culture that bolsters safety? The answer lies in replacing control with trust – not blind trust, but “Trusted Autonomy.” This leadership model centers on empowering employees with the autonomy to make decisions and take initiative, while building mutual trust and accountability up and down the hierarchy. It may sound idealistic to hard-nosed industry veterans, but data-driven results and case studies show that empowering, trust-based leadership yields stronger safety outcomes (Zacharatos et al., 2005; Rowell et al., 2024). In essence, Trusted Autonomy flips the script: instead of a supervisor hovering over every action, they provide clear goals and guardrails, then support their team’s judgment and expertise. Here’s how leaders can implement this model in practice:

- Establish Psychological Safety – No More “Fear of Speaking Up”: Leaders must actively cultivate an atmosphere where workers feel safe to voice concerns, admit mistakes, and share ideaswithout fear of punishment or ridicule. This involves simple but powerful changes: encourage questions during safety briefings, positively acknowledge employees who flag issues (reinforce that reporting is a good thing), and ensure that incident investigations focus on learning not blame. For example, one offshore wind firm revamped its incident review process to explicitly avoid individual blame and instead analyze system factors – within a year, near-miss reports tripled, giving the company far more opportunities to fix hazards (Rowell et al., 2024). The concept of a “Just Culture” is useful here (Dekker, 2007): frontline personnel should trust that they won’t be penalized for honest errors or near-misses as long as they report them and work to prevent recurrence. Executives in Europe are increasingly adopting policies to protect safety whistleblowers and reward hazard reporting (Rowell et al., 2024). By making it clear that raising a hand is welcomed – “Thank you for spotting that” – leadership can break the silence. When psychological safety increases, so does proactive safety behavior (Edmondson, 1999). Crews begin to function as true teams, catching each other’s mistakes and suggesting improvements, rather than hiding problems.

- Delegate Decision-Making and Encourage Ownership: Micromanagement often stems from a belief that “people can’t be trusted to make the right call.” Trusted Autonomy turns that around by training and equipping employees so that they can be trusted, and then granting them the autonomy to act. This aligns with the military’s “mission command” philosophy, where commanders set clear intent but give junior leaders latitude in execution (DeLeon & Tripodi, 2022). In an offshore context, this could mean empowering a turbine maintenance team to pause a job if conditions change, without needing senior approval – trusting their assessment. It could also mean involving workers in planning how to carry out tasks safely, rather than dictating every step. Leaders practicing Trusted Autonomy will delegate authority along with responsibility: for instance, allowing a drilling crew to adjust their work sequence on the fly if they identify a safer approach, as long as it meets the safety standards and goal. A study in human factors leadership found that when supervisors gave crews more control over how to meet objectives (within safe parameters), teams were more adaptable and had fewer procedural violations, because they weren’t trying to “work around” inflexible orders (Rowell et al., 2024). Importantly, delegation must be paired with skill development – which is where training comes in. Companies should invest in robust training for both technical skills and decision-making skills (Zacharatos et al., 2005). When workers feel competent and trusted, their intrinsic motivation soars, leading to better performance and innovation. As one offshore veteran put it, “When you know you’ve got autonomy and the trust of your managers, it incentivizes you to do better and achieve”. That is the essence of Trusted Autonomy in action.

- Transform Supervisors into Coaches, Not Controllers: The role of middle management is pivotal. Instead of the old-school foreman who barks orders and micromanages, we need supervisors who coach and mentor their teams. This requires a mindset shift and often, targeted leadership training. Programs in safety leadership and “human-factors leadership” should be implemented in oil and gas company training curricula to help managers build skills in communication, conflict resolution, and team empowerment. For example, teaching supervisors to use open-ended questions (“How can we make this task safer?”) rather than commands fosters two-way dialogue. Coaches also personalizetheir approach: a good safety leader knows their crew members’ strengths, weaknesses, and even personal stressors, and provides support accordingly. This might mean adjusting schedules when someone is fatigued or pairing a new worker with a veteran mentor. The payoffs of a coaching approach are significant. Research in organizational psychology shows that employees with supportive, fair managers report higher job satisfaction, lower stress, and commit fewer unsafe acts (Conchie et al., 2013). Coaching-style leaders also help diffuse bullying and harassment: by checking in regularly with team members, they can catch toxic behaviors early and model respectful conduct. In one case study from a North Sea platform, replacing an infamously autocratic supervisor with a more inclusive one led to a marked improvement in crew morale and a 40% reduction in incident reports year-over-year (anonymized internal company report, 2021). The new supervisor actively solicited feedback and intervened zero-tolerance on any bullying, which fundamentally changed the work atmosphere. The lesson: leaders set the tone, so we must select and develop those who can cultivate trust and respect rather than fear.

- Embed “Stop Work Authority” and Inclusive Safety Committees: A cornerstone of Trusted Autonomy is giving every worker the authority to halt operations for safety reasons – and crucially, backing them up when they do so. Many companies have stop-work policies on paper, but in practice workers may hesitate to use them if the culture is punitive. Leadership must reinforce that stopping work for safety is not just a right, but a responsibility. When a roustabout or a wind technician calls a timeout due to a concern, management’s reaction should be praise, not irritation. Publicly recognize those decisions as successes (the goal is to prevent accidents, after all). Additionally, create inclusive safety committees or forums where workers of all levels (including contractors, junior staff, and underrepresented groups) have a voice in safety decisions. For instance, an offshore energy company in the Middle East set up a safety council that included not just managers and engineers, but also a rotating group of crew members from different departments. This empowered frontliners to influence policies – such as improving the timing of safety drills to reduce fatigue – and led to practical changes. Over time, such involvement builds buy-in: workers see that safety isn’t just top-down rules, but something they collectively shape. It also helps break the power-distance barrier common in some cultures (especially in Middle Eastern and Asian contexts with traditionally high respect for authority). By flattening the communication on safety matters, companies can counteract the tendency to defer in silence. Inclusive leadership signals that everyone’s expertise is valued in managing risk, whether it’s a senior geologist or a junior deckhand. The more perspectives on a problem, the more robust the solution – a principle well demonstrated in high-reliability organizations from aviation to nuclear power.

- Address Psychosocial Risks Proactively (Mental Health is Safety): Finally, Trusted Autonomy means caring for workers as whole humans, not just cogs in a machine. Leaders should anticipate and mitigate the psychological and social stressors that come with offshore work. This involves policies and programs, such as: reasonable rota schedules to prevent burnout (e.g. avoid unnecessarily long hitches; research shows three weeks on/off is already taxing, with well-being dropping as rotations extend (Mette et al., 2018)), providing access to mental health resources (confidential counseling, stress management training, etc.), and enforcing anti-bullying and harassment standards with real consequences. It’s crucial that executives treat issues like fatigue, interpersonal conflict, or discrimination as safety-critical issues. One forward-thinking example comes from a major European wind operator that introduced a “well-being dashboard” for its offshore teams – tracking indicators like overtime hours, days since last shore leave, and even anonymous pulse survey results on morale – alongside traditional safety KPIs. This data is reviewed monthly at the board level, under the premise that psychosocial health is a leading indicator of safety performance. Indeed, a Malaysian study found that psychosocial hazards fully mediate the relationship between safety culture and safety performance – in other words, improving the psychosocial climate (by reducing stress and improving support) directly led to better safety outcomes (Isha et al., 2021). Leadership can take actionable steps like rotating workers through less intense assignments after particularly long or stressful projects, organizing team-building activities that strengthen camaraderie, and actively promoting diversity and inclusion (so that women and minority workers feel respected and heard on the job). These measures are not just “feel good” initiatives; they result in a more alert, engaged workforce that will catch that loose bolt or respond faster to that alarm because they’re not mentally drained or distracted by a hostile work environment. As Offshore Energies UK (2019) noted in its guidelines, treating mental well-being as a safety priority leads to tangible improvements – reduced sick leave, lower turnover, and a crew that’s “more alert, communicative, and productive”.

Conclusion: Leadership Transformation as the Key to Safety Performance

Micromanagement and control-oriented culture might have had their day in the industrial past, but they are ill-suited for the complexities of today’s offshore operations. The data is unequivocal that psychological factors – trust, respect, empowerment – are not “soft” topics, but hard determinants of safety. When executives and managers cling to control through fear, they inadvertently sow the seeds of chaos: errors go unreported, workers burn out or rebel, and the organization becomes brittle in the face of inevitable challenges. By contrast, adopting the Trusted Autonomy model creates a resilient, high-engagement safety culture. In such an environment, workers act as sentinels and problem-solvers, not just rule-followers. They feel responsible for safety, not just accountable to a boss.

For leaders in Europe, the Middle East, and beyond, this transformation requires humility and courage. It means unlearning the instinct that tighter control equals more safety, and embracing the evidence that empowering people and building trust yields superior outcomes. It also means holding up the mirror: senior leadership must model these values by trusting their own teams. As one example, after a spate of incidents, a Middle Eastern offshore contractor’s CEO publicly pledged to change his approach – he admitted that an overly punitive reporting system was suppressing information, and he replaced it with a non-punitive “learning” incident system. The result was a significant rise in reported near-misses (a positive sign) and a subsequent drop in serious accidents over two years (internal HSE report, 2020–2022). This mirrors a broader regulatory shift: new guidelines and laws are emerging (e.g. the EU’s upcoming directive on managing psychosocial risks at work) that will require companies to address issues like harassment, stress, and excessive control as part of their formal safety management. Forward-thinking companies are getting ahead of these changes by investing in leadership development and cultural change now.

In summary, The Leadership Awakening Series reminds us that true safety leadership is transformational. It is not about commanding and compliance alone, but about inspiring and enabling every person on the offshore platform or wind farm to be a safety leader in their own right. By escaping the micromanagement trap and fostering a culture of Trusted Autonomy, organizations can turn chaos into coherence. They can expect not only fewer accidents, but also higher productivity and innovation – because a workforce that feels safe to speak, to think, and to care will perform at its best. As the saying goes, “Trust is the highest form of human motivation.” Nowhere is that more evident than 100 miles offshore, where trust and teamwork can literally save lives. It’s time for our industry’s leadership culture to evolve accordingly, shedding the old control-freak mentality and rising to a higher standard of trust, respect, and safety for all.

References

Collins, S. K., & Collins, K. S. (2002). Micromanagement – a costly management style. Radiology Management, 24(6), 32–35. PubMed. (PMID: 12510608) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12510608/

D’Antoine, E., Jansz, J., Barifcani, A., Shaw-Mills, S., Harris, M., & Lagat, C. (2023). Psychosocial safety and health hazards and their impacts on offshore oil and gas workers. Safety, 9(3), Article 56. https://www.mdpi.com/2313-576X/9/3/56#:~:text=Several%20participants%20had%20worked%20under,P29

DeLeon, D., & Tripodi, M. (2022). Eliminating micromanagement and embracing mission command.Military Review, 102(5), 64–72. https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/September-October-2022/DeLeon-Tripodi/

Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://web.mit.edu/curhan/www/docs/Articles/15341_Readings/Group_Performance/Edmondson%20Psychological%20safety.pdf

Isha, A. S. N., Mohyaldinn, M. E., Leka, S., Saleem, M. S., & Syed Abd Rahman, S. M. N. (2021). Impact of safety culture on safety performance: mediating role of psychosocial hazard. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 4425. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8394037/

Mette, J., Grote, G., & Kolbe, M. (2018). Working in the eye of the storm: Stress experiences of offshore wind workers. BMC Public Health, 18(172), 1–12. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322669101_Healthy_offshore_workforce_A_qualitative_study_on_offshore_wind_employees'_occupational_strain_health_and_coping

Miller, P., Brook, L., Stomski, N. J., Ditchburn, G., & Morrison, P. (2020). Depression, suicide risk, and workplace bullying: A comparative study of fly-in, fly-out and residential resource workers in Australia. Australian Health Review, 44(2), 248–253. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30995951/

Murphy, K., Strand, L., Theron, L., & Ungar, M. (2021). “I just gotta have tough skin”: Women’s experiences working in the oil and gas industry in Canada. The Extractive Industries and Society, 8(2), 100882. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2214790X21000277#:~:text=Gender%2Dbased%20harassment%20is%20common,to%20survive%20in%20the%20workplace.

Rowell, G., Smith, J., & Hanssen, P. (2024). Offshore-wind health and safety: A review and analysis.Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews, 173, 113045. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364032123007864

Zacharatos, A., Barling, J., & Iverson, R. D. (2005). High-performance work systems and occupational safety: A study of automotive assembly plants. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 77–93. https://hosted.smith.queensu.ca/faculty/julianbarling/BooksChapters/HPWS%20and%20OS1.pdf