Speaking up or shutting down: creating psychological safety 500 feet above the sea

Part 3 of the Leadership Awakening Series

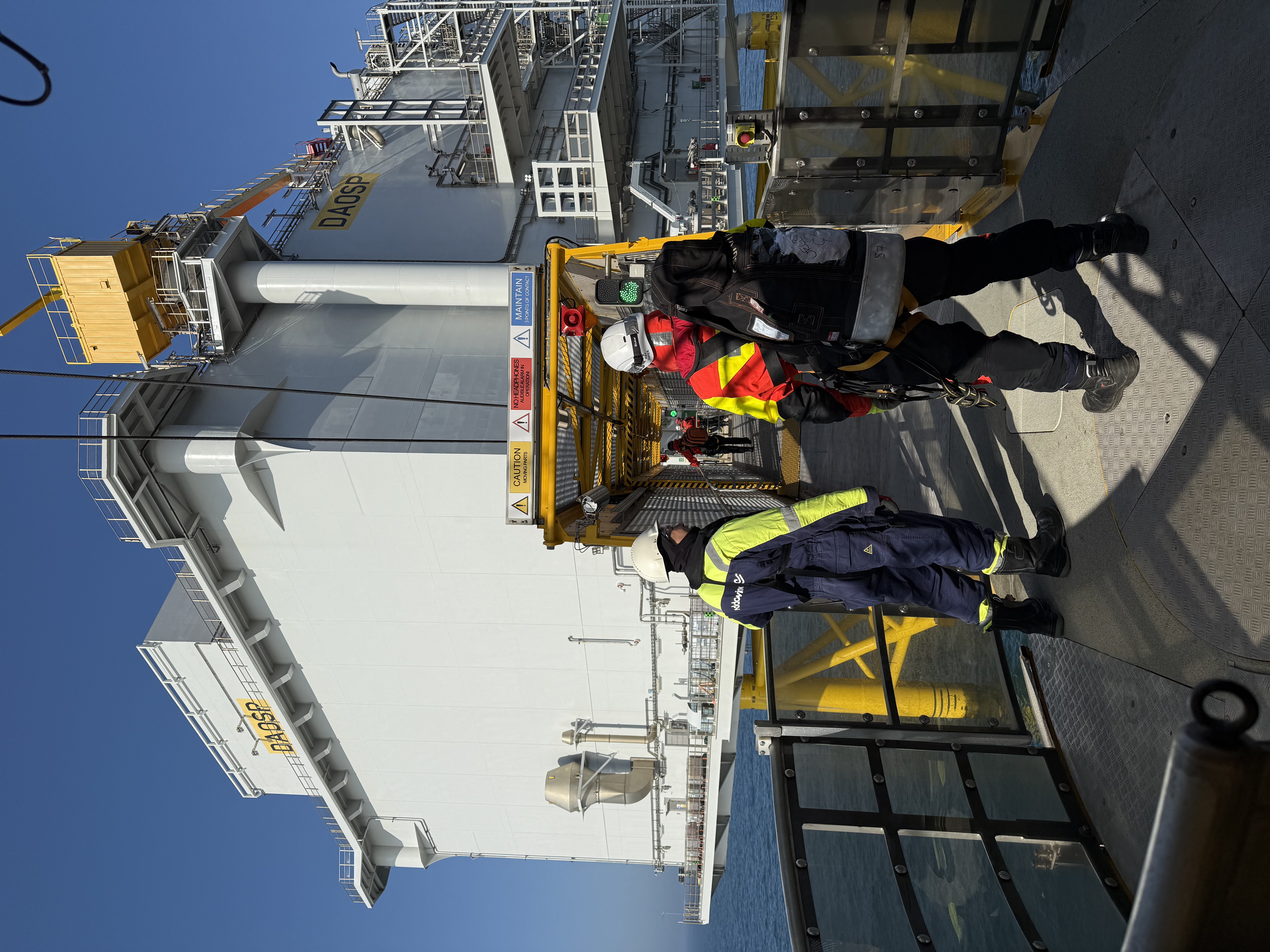

Offshore platforms, whether towering wind turbines or oil rigs, are some of the most hazardous workplaces on earth. Workers find themselves 500 feet above the sea, facing harsh weather and high-stakes tasks. In these conditions, an insidious threat to safety often lurks: a culture of silence. When crew members hesitate to voice concerns or stop unsafe work, small hazards can snowball into catastrophes. To prevent this, psychological safety, the shared belief that it’s safe to speak up with ideas or concerns without fear of punishment, is just as essential as hard hats and harnesses. This article explores why fear of speaking up is a systemic failure that multiplies risk, and offers a data-driven, step-by-step guide for leaders to establish a “speak-up” safety culture on offshore platforms. The focus is on Europe and the Middle East, where rapidly expanding offshore wind and energy projects demand a new caliber of safety leadership.

When Safety Culture Shuts Down Voice

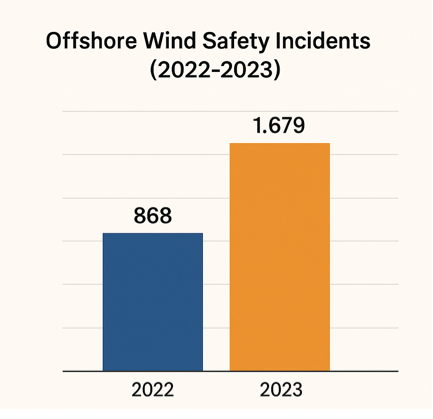

Despite strong safety records in European offshore energy, recent trends expose cracks in the culture. New data show a 94% surge in global offshore wind safety incidents from 2022 to 2023 – jumping from 868 to 1,679 reported incidents. This jump occurred even as hours worked increased, suggesting that as the industry scales up, more problems are being encountered or reported. While encouragingly, the share of high-potential (severe) incidents fell, the spike in total incidents rings an alarm bell. It underlines that many hazards are still being caught late (or not at all) until something goes wrong.

Why are so many issues only identified after an incident? One answer lies in how safe workers feel to voice concerns. Psychological safety at work means people feel comfortable sharing concerns and mistakes without fear of embarrassment or retribution. In a psychologically safe team, a technician who spots a loose bolt at 300 feet height will immediately call it out; a junior crew member will question a procedure that “just doesn’t seem right,” even if a senior engineer is in charge. Unfortunately, in many offshore operations, workers instead shut down—choosing silence over speaking up—because they fear the consequences of honest dialogue.

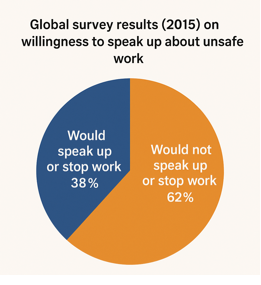

Fear in Numbers: Most Workers Stay Silent

This isn’t just intuition; it’s backed by data. In one global survey of 2,600 workers across industries, over 60% said they would not speak up or intervene if they saw something unsafe, even though nearly all said their company officially had a “stop-work authority” policy. In other words, six in ten workers would bite their tongue rather than halt a dangerous situation, largely due to fear of retaliation or peer pressure (Morrison, 2015). Such fear can be even more pronounced in highly hierarchical cultures. For example, researchers in Pakistan’s petroleum sector (a context culturally similar to many Middle Eastern workplaces) found that a “bureaucratic culture” poses major challenges to those who dare to speak up, underscoring the need for ethical leadership and trust before employees will raise their voice (Zhu et al., 2022).

The offshore environment has unique factors that historically discourage speaking up. Many European wind farms and Middle Eastern rigs rely on tiered contracting like local contractors or short-term hires who may feel disposable. One recent qualitative study of North Sea oil workers found fear of speaking up was most acute among temporary or “casual” workers, who worry that if they make waves, they won’t be hired back (D’Antoine et al., 2023). In interviews, some offshore workers bluntly described speaking up as “booking a window seat on the next flight out of here” – a fast-track to getting fired. This macho, “grin-and-bear-it” culture also extends to health: male-dominated crews often discourage admitting fatigue or illness, so workers hide symptoms rather than appear “weak”. In Middle Eastern operations, additional cultural layers of deference to authority can further amplify silence. Junior staff may feel it’s not their place to question a supervisor, especially if expatriate workers fear visa or job loss.

The net effect is a culture where problems stay hidden until they manifest in accidents. Every veteran of the industry can recount near-misses that were “accidents waiting to happen” because someone down the chain noticed something wrong but said nothing. And indeed, many infamous disasters have been traced to this dynamic of unspoken warnings. The 1986 Chernobyl nuclear meltdown is often cited as a textbook case: a rigid hierarchy meant technicians were hesitant to question a risky test procedure mandated by their boss, leading to a catastrophic sequence of events. In the 1988 Piper Alpha offshore rig explosion in the North Sea, which killed 167 people, investigators found that a breakdown in communication during shift handover – and an environment where workers didn’t feel empowered to flag concerns – contributed to the tragedy. A permit that a critical valve was out for maintenance was misplaced or ignored; the night crew, unaware of the hazard, restarted a pump, triggering a gas leak and then the fatal blast. One survivor later recounted that workers had been afraid to speak up about safety lapses due to a culture of fear and “check-the-box” complacency (Khan, 2025). These examples show how fear of speaking up isn’t just a personality issue. It’s a systemic failure of the safety culture, in which latent hazards multiply unchecked until disaster strikes.

Why Speaking Up Saves Lives

Fostering psychological safety is not about coddling workers’ feelings. It is a proven lifesaver in high-risk industries. Research has consistently found that when employees feel safe to voice concerns, organizations catch problems earlier and have better safety outcomes. A landmark study of 7,505 Norwegian offshore oil rig workers found that supportive leadership and giving employees more job control were strongly associated with more frequent safety voice (reporting hazards and speaking up), and in turn, higher safety performance. Crucially, teams where people spoke up more had significantly lower perceived safety risk and fewer personal injuries (Mathisen et al., 2022). In short, empowering workers to raise concerns correlates with real reductions in accidents and injuries.

Recent meta-analytic evidence reinforces this link. A 2023 review combined 49 studies encompassing over 50,000 employees across industries. It confirmed that safety voice thrives in environments that actively support it, and it directly improves safety compliance and behaviors on the job (Tedone et al., 2023). Workers speak up far more when their leaders are approachable, listen, and respond positively, and when coworkers share a norm of vigilance. In turn, those who speak up tend to also follow safety procedures more diligently and help others do the same, creating a virtuous cycle (Tedone et al., 2023). Notably, this effect held even beyond the influence of training or individual safety knowledge. In other words, all the safety training in the world may not stick if the culture on the ground discourages open communication. Conversely, even average workers with modest training will achieve superior safety outcomes in a climate where everyone is encouraged to “see something, say something.”

It’s not hard to see why. On an offshore wind turbine 150 meters high, a technician might notice an unusual vibration or an out-of-place tool. If they feel psychologically safe, they’ll report it immediately through the radio or to a supervisor, allowing a timely fix before a failure occurs. If they feel intimidated or assume they’ll be ignored, they might stay silent – and that tiny anomaly could later cause a dropped object or equipment breakdown. The same goes for near-misses: a culture that treats near-misses and “good catches” as learning opportunities will accumulate a rich data bank of hazards to eliminate. A culture that punishes or downplays reporting will remain blind to those hazards until an injury forces them into view.

Leaders in high-reliability organizations often say they want an “informed culture” where bad news rises quickly. Psychological safety is how you get it. As one executive succinctly put it, “We never want to hear ‘I knew about the problem but didn’t say anything.’” Creating that openness requires deliberate effort. Companies like Ørsted, a global offshore wind leader, explicitly tie psychological safety to their safety strategy. Ørsted states that “psychological safety is as important as physical safety, and our culture is rooted in trust and respect” – a viewpoint now guiding their team training and onboarding (Ørsted, n.d.). This forward-thinking stance is increasingly echoed by major players in Europe’s renewable sector and by multinational oil & gas firms operating in the Middle East. They recognize that in the long run, a culture of silence is incompatible with world-class safety performance.

How to Build a Speak-Up Safety Culture Offshore

Changing a culture of silence into one of open communication won’t happen via memo. It requires systemic action. Below is a step-by-step guide for establishing “voice safety protocols” and embedding psychological safety in offshore teams. These steps blend evidence-based practices from recent research with actionable takeaways that industry executives can start implementing immediately.

1. Start at the Top: Make Speaking Up a Core Value (and Mean It)

Transformation begins with leadership. Executives and managers must overtly and repeatedly communicate that speaking up about safety is not only allowed but expected. Issue a clear “stop-work authority” policy(if one isn’t already in place) that empowers any worker to halt an operation over safety concerns. More importantly, model it. Leaders should publicly thank and positively reinforce employees who raise a concern, especially if it turns out to be a false alarm. This signals that the act of speaking up is valued in itself. Research shows that supportive leadership is a key driver of safety voice. So, conduct leadership training on how to respond constructively when front-line workers bring up issues. Leaders need to learn to avoid defensive or dismissive reactions. An abrupt put-down like “We don’t have time for that” will echo throughout the crew and shut others down. Instead, train supervisors to say “Thank you for flagging that. Let’s check it out.” If senior managers demonstrate zero tolerance for retaliation and visibly have workers’ backs when they speak up, trust will grow. A strong message from the C-suite can also pre-empt cultural resistance: for example, a CEO might send a video to all crews stating,

“No one will ever lose their job for stopping work in a dangerous situation. You’ll be praised for it.”

When leadership walks the talk, psychological safety gains a foothold.

2. Establish Clear “Voice” Channels and Protocols

It’s not enough to tell people to speak up; organizations must create tangible mechanisms for it. Develop clear protocols for reporting hazards, near misses, and improvement ideas. This could include an anonymous reporting hotline or a simple digital app that offshore technicians can use to submit safety observations (with quick feedback guaranteed). Set up regular safety meetings (e.g. weekly “safety circles” or after-action reviews) where employees at all levels are invited to share concerns and lessons. Structure these meetings to be blameless problem-solving sessions. For instance, some North Sea operators have instituted daily toolbox talks that begin with a prompt:

“Does anyone have any safety concerns or near-misses to share from yesterday?”

Make it standard that each concern raised gets an acknowledged follow-up. By creating a loop – report, respond, resolve – employees see that speaking up leads to action, not a black hole. Over time, this builds confidence in the system. Companies can also incorporate “voice metrics” into their HSE dashboards, such as tracking the number of safety suggestions submitted or work stoppages initiated by crew. When those numbers go up initially, don’t punish it – celebrate it as a sign of a healthy reporting culture (as long as actual incidents aren’t spiking in severity). In the 2023 G+ offshore wind report, industry leaders noted a “step change in the reporting culture” in some areas, indicating more issues being caught proactively. Those are the organizations that will prevent the next accident.

3. Encourage and Empower

A true speak-up culture empowers every individual, not just veterans or managers. Make empowerment concrete: train every worker in hazard recognition and explicitly give them the authority to stop work or sound an alarm if they suspect something’s wrong. Many firms print this on cards or helmets (“You have Stop Work Authority – No repercussions”). But empowerment also has a softer side: encourage experienced crew to mentor newer ones on voicing concerns. Pair up less experienced workers with “safety buddies” who model asking questions and intervening. Reinforce that safety is everyone’s job. When a junior technician does speak up, amplify their voice – for example, at the next all-hands meeting, a manager can share,

“Last week, Jane noticed an anomaly in a lift procedure and spoke up, potentially preventing a serious incident. Great job, Jane.”

This not only recognizes that individual, it sends a powerful message across the crew that speaking up is heroic, not heretical. Policies should also explicitly protect whistleblowers and complainants; even in Middle Eastern operations where labor laws may not robustly safeguard workers, company-internal policies can fill the gap by promising job security to those who flag safety issues. Over time, as workers see peers praised (not punished) for raising their voice, the fear barrier erodes.

4. Invest in Psychological Safety Training and Coaching

Just as workers receive technical training, they benefit from learning communication and teamwork skills for high-stress environments. One proven approach is adapting Crew Resource Management (CRM) training – pioneered in aviation – to the offshore context. Aviation’s CRM focuses on flattening hierarchies in the cockpit, teaching juniors how to assertively voice concerns and seniors how to listen. After CRM was implemented, airlines saw major drops in accidents attributed to human error. The offshore wind industry is already borrowing these lessons. For example, a safety leadership program called “Thrive” was deployed for all teams on the Hornsea Two wind farm (UK), using immersive simulations to role-play speaking up and responding under pressure. Such programs emphasize that silence can be deadly, and communication saves lives. Organizations should incorporate psychological safety modules into supervisor training and onboarding for new hires. Techniques include teaching workers how to phrase a concern (e.g. using factual observations and assertive language) and teaching leaders active listening and calm acknowledgment. Even simple drills can help – for instance, practice scenarios where a trainee must stop a task and shout “Stop work!” upon noticing a defect, to normalize that behavior. Coaching is also valuable: on rigs, some companies designate a respected veteran as a “safety coach” whom crew can confidentially approach with issues. This coach can then help convey the concern or advise the worker on how to escalate it. By building these skills and support structures, you make speaking up feel less socially daunting and more like second nature. Health4Wind offers both Training and Coaching to support your operation.

5. Reward Reporting and Learn from Every Incident (or Near Miss)

To sustain a speak-up culture, reinforce it through rewards and learning. Align incentives so that leaders and teams are recognized not just for hitting production targets, but for demonstrating safety vigilance. Some firms have introduced awards for “Best Safety Intervention of the Month” or similar, where management highlights a case where an employee’s proactive voice averted a risk. This shifts the hero narrative: the heroes are not those who work around a hazard to get the job done, but those who call a timeout to address it. Ensure that incident investigations and near-miss analyses focus on what can we learn, not who can we blame. When people see that the organization responds to mistakes or close calls with curiosity and improvement rather than punishment they become more willing to speak openly. For example, if a lifting operation nearly fails, conduct a blameless post-mortem and widely share the lessons (e.g. “Crane operator voiced discomfort with the wind speed and halted the lift preventing a possible tip-over. We realized our guidelines for wind limits needed clarification, which we’ve now updated.”). Such transparency shows that raising issues leads to positive change. Over time, this builds a “just culture” where workers know they won’t be vilified for genuine concerns or mistakes. In Europe, regulatory shifts are already encouraging this approach – the EU’s focus on human factors and the UK’s safety-case regime put premium on organizations demonstrating a learning culture. Smart executives will get ahead of these shifts by baking learning and voice into their safety management systems now.

6. Measure, Monitor, and Adapt

Finally, treat psychological safety and safety voice as measurable outcomes that you continually monitor and improve. Conduct periodic anonymous surveys of your workforce to gauge their comfort in speaking up. For example, you can include statements like “I feel safe challenging a decision if I think it might jeopardize safety” and see how strongly teams agree or disagree. Track these metrics over time and by department or vessel. If certain units report low psychological safety, focus interventions there – maybe leadership coaching or facilitated workshops to rebuild trust. Pay attention to hard indicators too: frequency of safety suggestions, stop-work reports, and near-miss reporting rates are all clues to your speak-up culture. Aim for increasing reporting of near misses (a sign of vigilance), paired with decreasing actual injury rates – that’s the golden combination indicating you’re catching more issues proactively. If instead you find workers still hesitating – e.g. incidents where after the fact people say “Yeah, I noticed that but didn’t say anything” – treat it as a serious process failure. Investigate why the person stayed silent; was it a fear of ridicule? Time pressure? Supervisor attitude? Use that insight to adapt your training or policies. Creating psychological safety is not a one-and-done project – it’s an ongoing leadership practice. Especially in dynamic sectors like Middle East oil fields or North Sea wind farms, new crews and contractors come in regularly, so the effort to indoctrinate everyone into the speak-up culture must be continuous. Consider incorporating psychological safety goals into managers’ performance appraisals (for example, requiring a certain number of safety engagement sessions, or evaluating teams’ survey results). What gets measured gets managed.

Conclusion: The Future of Offshore Safety Hinges on Voice

“Speaking Up or Shutting Down” is literally a life-or-death choice 500 feet above the sea. The data and case studies are clear: when people fear speaking up, accidents proliferate; when people are empowered to speak, safety soars. Building a culture of psychological safety in offshore wind and oil & gas isn’t a touchy-feely initiative. It’s a pragmatic strategy to reduce injuries, downtime, and even fatalities. It requires leaders to challenge deep-seated norms, from the “production-first” mindset that plagued Piper Alpha to the rigid hierarchies still found on some Middle Eastern installations. It means being forward-thinking: anticipating that regulators will increasingly scrutinize corporate safety culture (with concepts like ISO 45003 on psychosocial risk management), and that the next generation of workers expects a more open, inclusive workplace. Most of all, it means recognizing that safety leadership is not just about procedures and engineering, but about psychology, in other words, how people perceive their ability to contribute and be heard.

The encouraging news is that transformation is possible. As we’ve seen, companies that have made psychological safety a priority (investing in training, clear protocols, and leadership development) are already reaping benefits in incident prevention. They are turning what could be a controversial stance (that maybe it’s okay to stop work and miss a deadline if someone raises a concern) into standard operating procedure backed by data. These organizations treat a worker questioning a supervisor not as insubordination but as innovation in safety. Such a shift may feel challenging, but it is achievable with commitment and the systematic steps outlined above.

For executives in Europe and the Middle East leading the offshore energy boom, now is the time to act. Every crew member who climbs a turbine or boards a platform must know their voice matters more than their rank, and that silence helps no one. By creating an environment where speaking up is championed, where the default response to a concern is “thank you,” leaders can unlock the full safety potential of their teams. The result will be a more resilient safety culture that not only prevents accidents but also enhances overall performance, morale, and innovation. In the high-risk offshore world, psychological safety is the new frontier of safety leadership. Those who master it will not only save lives but also lead the industry into a safer, smarter future.

References

Active Training Team. (n.d.). We are all leaders when it comes to safety. ATTWhitePaper_Safety_Offshore_Wind_Industry. https://activetrainingteam.us/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/ATTWhitePaper_Safety_Offshore_Wind_Industry.pdf#:~:text=as%20being%20technically%20competent,Dr%20Flin%20has

D’Antoine, E., Jansz, J., Barifcani, A., Shaw-Mills, S., Harris, M., & Lagat, C. (2023). Psychosocial Safety and Health Hazards and Their Impacts on Offshore Oil and Gas Workers. Safety, 9 (3), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety9030056

Energy Institute. (2024, June 13). Offshore wind safety performance mixed amid record 61.9 million hours worked (Media release). Energy Institute News Centre. Retrieved from https://www.energyinst.org/.../offshore-wind-safety-performance-mixed-amid-record-hours

Mathisen, G. E., Tjora, T., & Bergh, L. I. V. (2022). Speaking up about safety concerns in high-risk industries: Correlates of safety voice in the offshore oil rig sector. Safety Science, 145, 105487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105487

Morrison, K. W. (2015, May 22). Stop-work authority: Empowering workers to halt a dangerous situation can help prevent injuries. Safety+Health Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandhealthmagazine.com/articles/12346-stop-work-authority

Ørsted. (n.d.). Our Culture and Values – Wellbeing at Work. Ørsted Careers. Retrieved July 30, 2025, from https://us.orsted.com/careers/working-at-orsted/our-culture

Tedone, A. M., Mesmer-Magnus, J. R., Newkirk, E., Viswesvaran, C., & Horta, L. (2023). I Speak Up Because You Care: A Meta-Analytic Review of Safety Voice as a Social Exchange. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2023(1), Article 13548. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMPROC.2023.10999abstract

Zhu, H., Khan, M. K., Nazeer, S., Li, L., Fu, Q., Badulescu, D., & Badulescu, A. (2022). Employee Voice: A Mechanism to Harness Employees’ Potential for Sustainable Success. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(2), 921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020921